The original Molly Maguire

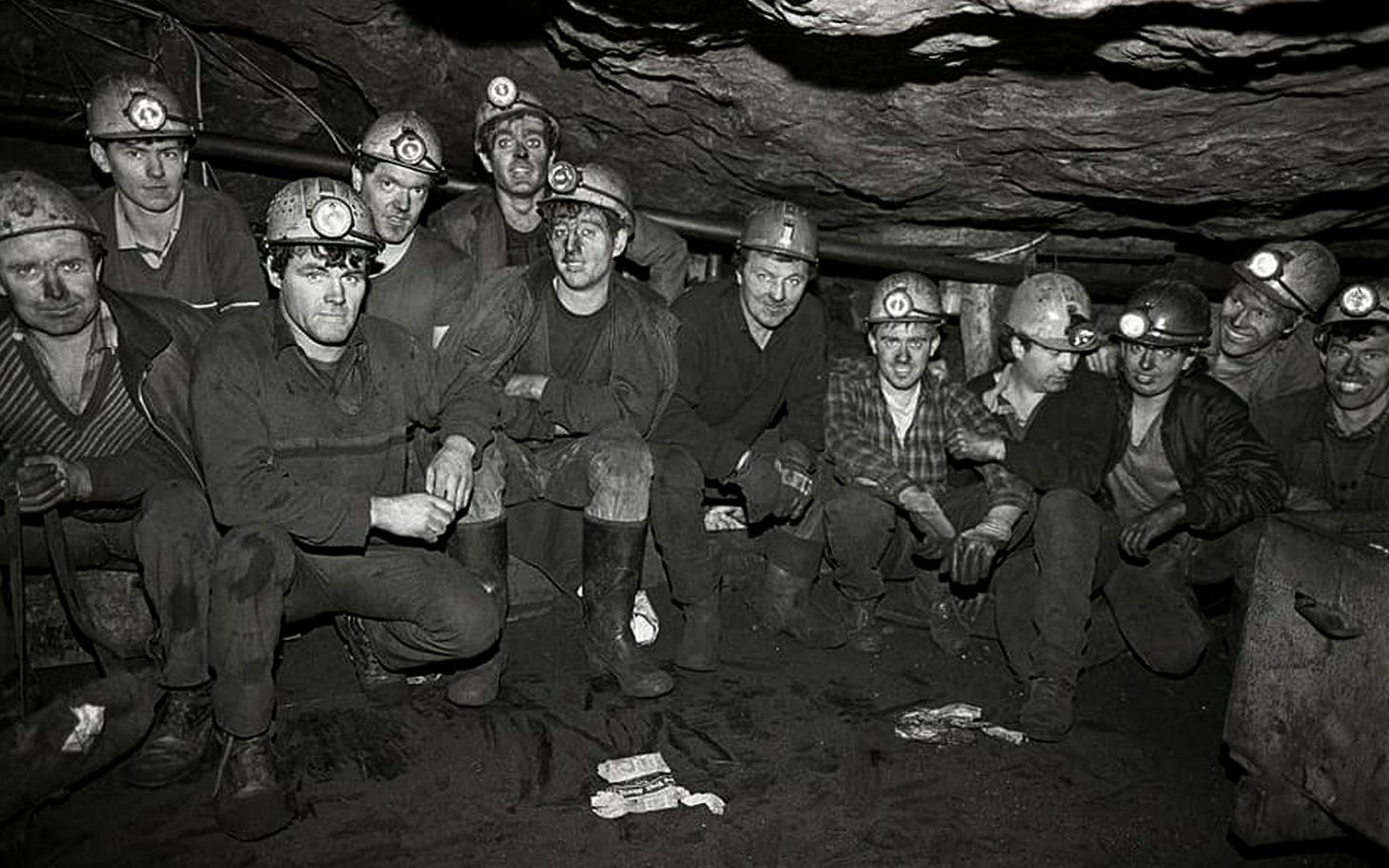

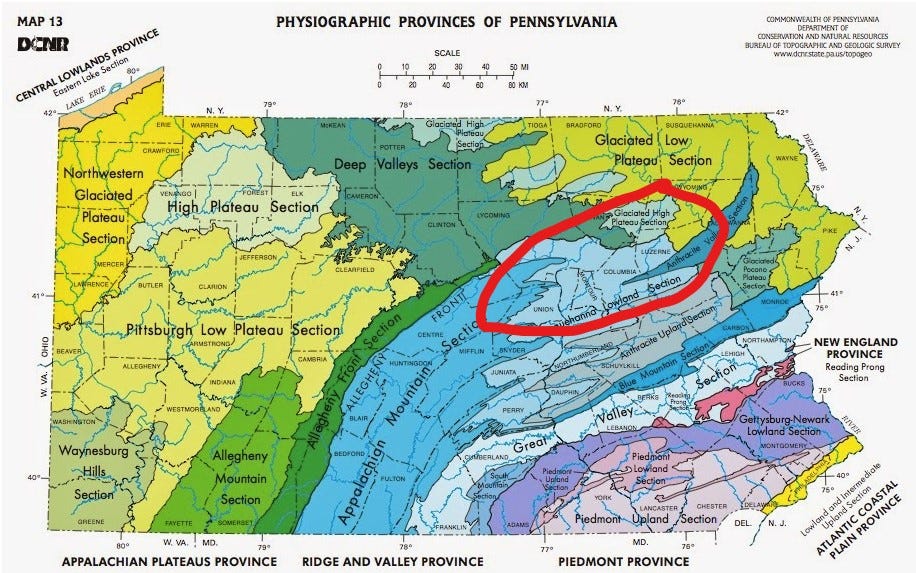

Having frequently driven through the ruggedly gorgeous terrain of northeast Pennsylvania’s coal country in a travelling job, I have been intrigued by the prospect of how men in times past drew their livelihood from that forbidding place. From the comfort of an air conditioned, fuel-injected rental car it looks attractive; from 1,000 feet down inside an anthracite mine, probably not so much.

This story takes us back 150 years to the first organized — and bloody — labor movement in America’s coal mines. But the story begins in Ireland.

Molly Maguire was an Irish Catholic widow, c. 1840, who refused eviction from her home. According to legend, her landlord set fire to her house with her inside, killing her. The historical backdrop was the labor unrest in northern Ireland where miners — including children — worked overlong shifts in murderous conditions.

Seizing on the death of the original Molly, labor agitators (men cross-dressed as women for disguise) carried out sabotage against mine owners.

And then, the Great Potato Famine

The Irish potato crop first failed in 1845 due to infestation by Phytophthora infestans, and it stayed failed through 1852. In that 7 year period, Ireland lost almost 3 million residents, half to starvation and malnutrition, the other half to immigration.

America beckoned.

Thousands of Irishmen found their way to the anthracite coal regions of northeastern Pennsylvania, in particular Schuylkill County, near Allentown. Mining was what they knew, and 19th century America’s appetite for coal — and coal profits — was insatiable.

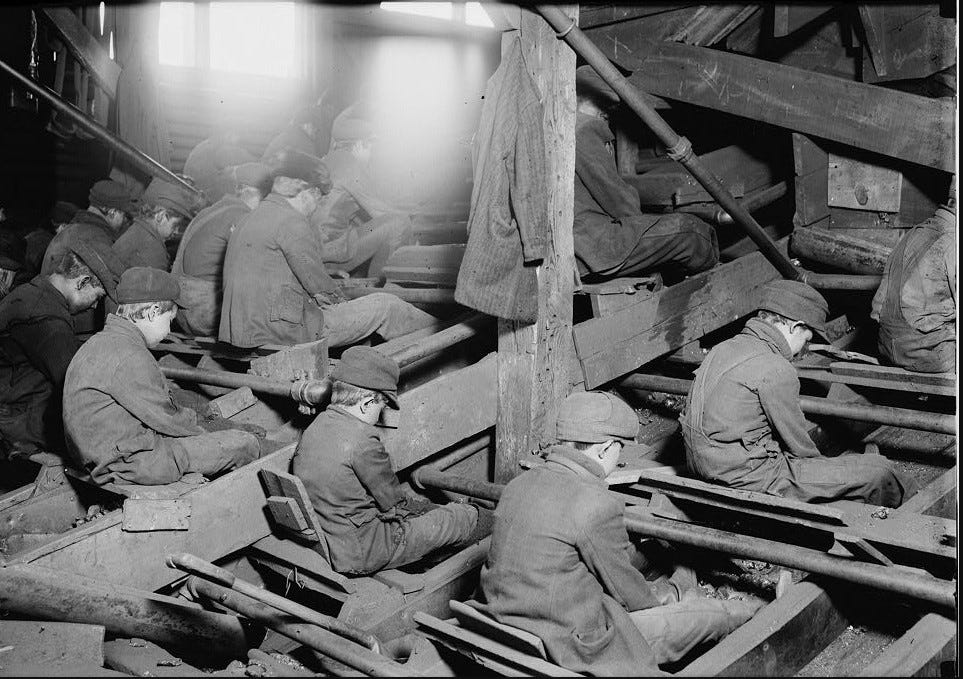

By any objective measure, working conditions in the Pennsylvania mines were atrocious. In Schuylkill County, 22,000 miners included 5,000 children, some as young as 5 years old.

A fire at the Avondale Mine in 1869 killed over 100 workers, allegedly because there was only one way out; no safety exit had been provided.

During this decade, over 2,000 casualties were incurred in the mines, including 500 deaths, due to poor ventilation, inadequate scaffolding and flooding.

Miners found it intolerable. And deadly.

The big economic picture

From the beginning of the nation, the U.S. experienced frequent financial disruptions: 1797, 1819, 1837, 1857, 1873, 1893, 1907, 1929. The Panic of 1873 started over railroad bonds and was fueled by repercussions of the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

The monetary disruption that matured in 1875 became known as The Great Depression (until the one in 1929 superseded the title), but before that, mining wages (already low, and paid in company scrip useful only at the company store) were cut as mine owners tried to remain profitable.

Miners had already found that their jobs were not only deadly, but financially ruinous. The remoteness of the area forced them to live in company-owned housing and trade with the company-owned store. Each year’s end frequently found them with accumulated debt greater than the year before.

A reduction in wages was out of the question.

The old ways died hard

In the old country, organized opposition to mine owners was rooted in the tradition of secret societies and given voice in violent assault, arson and murder. In Pennsylvania, the Molly Maguires reappeared to protest working conditions and reduced wages.

And also, true to their Irish roots, merely to protest; but it took a deadly turn.

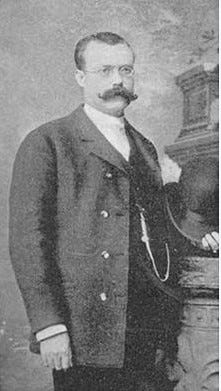

Two dozen of the bosses — foremen and superintendents — were murdered by various means, and in 1873 Frank Gowan, a mine owner and president of Philadelphia & Reading Railroad, hired the Pinkerton Detective Agency to ferret out the evildoers.

Pinkerton sends in 007

Not really.

The 1970 movie The Molly Maguires stars a young Sean Connery in the role of John Kehoe, a labor agitator. Richard Harris plays Irish-born James McParland, a Pinkerton undercover investigator. The movie is worth streaming, for no other reason than to view the accurate detail of coal mine operations.

The nature of the work is heartbreaking.

The unrealistic parts of the movie are where the conspirators are shown taking a break to have lunch among the coal and spin their schemes. I don’t think they ever had time to stop and eat.

Under the alias of James McKenna, agent McParland spent two years in the mines, working alongside the men and ingratiating himself to Molly Maguire leadership. The Workingmen’s Benevolent Association (WBA) provided cover for the unrest, as did the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH).

McKenna’s (McParland’s) investigative report resulted in lengthy trials of a score of protesters, among them John Kehoe, leader of the AOH, who was subsequently executed.

‘The day of the rope’

On June 21, 1877, 10 miners met the hangman. In a few years, 10 more had been tried, found guilty and hanged. These events represented the largest mass execution ever carried out by the U.S. government.

Interestingly, the prosecuting attorney at the first trial was none other than Frank Gowan himself, the mine owner who had hired Pinkerton in the first place. Most of the evidence was based on McParland’s testimony, prompting incalculable bitterness from his countrymen.

Was that true, or was it merely bigoted yellow journalism of the time? It is hard to make a judgment; the passage of time and the vitriol of the events make an undecipherable smear of bias and fact.

Later on

Violent labor unrest eventually came to an end, but not without other shocking bloodshed in American history: The Haymarket Square Bombing in 1886, the Pullman Strike in 1894, the Ludlow Massacre in 1914, among others.

The Pinkertons went on to continue their detection work, chasing Jesse James, the Younger Gang, and of course Paul Newman and Robert Redford.

Just kidding.

A Christian response

Hard to know where to start.

I have been conflicted by the story of the Molly Maguires in the Pennsylvania coal mines since I first read of it some 30 years ago.

McParland/McKenna is a hard man to see as a hero. He betrayed John Kehoe, his countryman. The two worked alongside one another for 18 months in some of the most physically demanding work the world has ever seen. A certain camaraderie would have been unavoidable.

Conditions in the coal mines were just short of a death sentence. Just as in Ireland of that era, boys of ages in the single digits were sent to work below grade, and could expect nothing from life but hardship, exhaustion, bronchial disease, poverty and early death.

That had to change, and deeply flawed men like Kehoe resisted the oppression with their chosen tools: Gunpowder and violence.

Equally flawed men like McParland stood against him and sided with the oppressors. McParland’s tools were falsehoods and misrepresentation. I’m not quite sure what evil that level of dissimulation would create in a man, but it feels very wrong.

A third way was desperately needed, and eventually it came about through legislation to improve working conditions, establish mine safety standards and abolish child labor.

For Kehoe and McParland, it was about 50 years too late.

The Apostle speaks

I stretch to find Biblical guidance. The best I can come up with is Paul’s dilemma in the 6th and 7th chapters of Romans.

Chapter 6 declares the Apostle’s conviction that he stands before God clean of his sin, justified by the pure atoning blood of Christ. He should rightfully exult in his newfound freedom from the oppression of sin.

But Chapter 7 admits that he remains torn by his old nature (“the flesh”) which refuses to let him enter the blessedness of obedience: “I end up failing to do the good I know is right, and instead, I find myself doing the evil I know is wrong.” (Romans 7:19, the Schuylkill-Ghormley Loose Living Translation.)

The confession in Romans 7:24 Wretched man that I am! Who shall deliver me from the body of this death? is heart wrenching. But the cry of victory is sublimely joyful in the following verse: Thanks be to God, Who delivers me through Jesus Christ our Lord!

It’s good news, but it gives little guidance to either Kehoe or McParland. Perhaps they both needed to leave the coal mines and pour their not inconsiderable creative energies into championing reform. While ministering grace to others along the way.

It challenges me: What efforts today require my energies?

Verse for the Week

John 16:24 In this world you will have trouble. But take heart! I have overcome the world.

Okay… none of us has to work the coal mine under 19th century conditions. But there are those in this world who do. Outside our borders, child labor, slave labor and labor paid so low as to be indistinguishable from slavery exist today.

Much of it is related to harvesting rare earth elements to support lifestyles these modern miners will never in their lives see: Electric vehicles, solar panels, wind generators, smartphone cameras, power steering and extremely awesome car stereo speakers. And many others.

Maybe more on that later. Meanwhile, let’s enjoy our air conditioning and try not to think too much about it. :-(

Curt

Share this post