September 20, 2023

The Cleveland Oil Massacre

The study of history is a curious thing. Mostly, it shows how others did their life and times wrong, so that when we do our different life and times wrong the same way, we can say, “Oh yeah, I guess it’s not as easy as it looked.”

Don’t be put off by the episode title; this is not a bloody story. There is no real massacre in the sense of people being murdered — al least not more than one, anyway — it’s just good old fashioned American capitalism at work.

Much – but not all – of the following information comes from an April 15, 2012 article in American History USA by Dan Bryan.

Okay, bear with me here. Following is a very short history of oil production as it affected North America. Early on, this was a search for how make fire transportable without bringing a wagonload of timber with you.

1770: Enterprising sailors like Captain Ahab chased down Moby Dick and his aquatic family, processed the blubber and sold whale oil. Thus, the whale oil lamp. Whale oil was liquid and easily moved. By 1846, the whaling industry accounted for over 80% of global shipping.

1846: Canadian geologist Abraham Gesner spoiled the whaling business by skimming “black water” from creeks and refining it. Kerosene was born. It was one-tenth the price of whale oil.

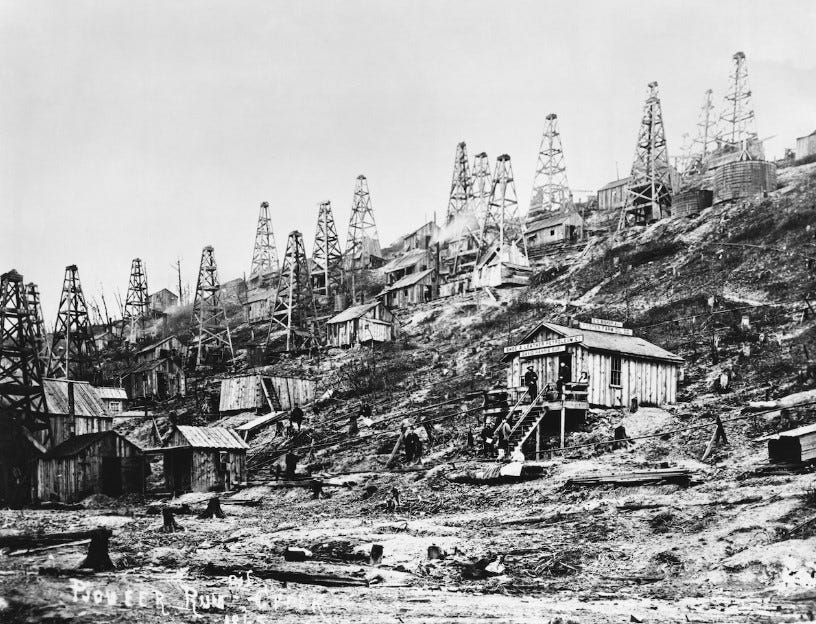

1860: George Bissell and Edwin Drake found black water in Pennsylvania, drilled a wildcat well and took 4,000 barrels of oil from it in the first year. Oil was in the ground — who knew? It was not exactly free, but it was plentiful and there for the taking.

The early oil industry included drillers (finding it), refiners (producing it), traders (buying and selling it), and transporters (shipping it).

Cleveland

Cleveland, Ohio, became a center of refining. Pennsylvania crude, procured by drillers, was freighted in by train. A score of Ohio refineries turned it into kerosene sold to New York City traders. The traders ordered the kerosene shipped to markets, mostly in large cities and mostly in the east.

One of those Ohio refiners was John D. Rockefeller.

By the late 1860s, the oil business in Cleveland was facing a crisis of overproduction. The refining capacity in the city far exceeded the amount of oil being pumped, leading to losses for many.

Enter Rockefeller, attentive, capable, ambitious and shrewd.

Rockefeller formed a partnership with Henry Flagler and, in 1870, they officially registered The Standard Oil Corporation.

Initially they were rejected for bank financing because of the glut of producers. The two took an enormous financial risk and declared a 40% stock dividend in the first year, depleting most of their cash to meet the payouts. The dividend attracted sudden attention and the new company was overwhelmed with investment capital.

Overt Aggression

Beginning the first day of 1872, Rockefeller approached a handful of railroad magnates with a proposition. Together, they formed the South Improvement Company. Standard Oil would guarantee regular oil shipments in return for a bulk rate discount. This allowed him to reduce his cost to selected New York traders, who could not only improve their profits but also offer their customers more predictable shipment schedules.

February 26, 1872: Railroad shipping rates, under the announced agreement, doubled overnight for every refiner except Standard Oil.

Competing refineries, drillers, and the traders who were not part of the deal immediately recognized the devasting effect this would have on their business.

Riots erupted. The Titusville (PA) Opera House was seized by thousands of protesters. Standard Oil billboards were defaced. Newspapers printed daily reports castigating Standard Oil.

Rockefeller received death threats, hired private security, slept with a revolver under his pillow.

Everyone, save for a select few, hated John D. Rockefeller.

Covert Campaign

While the world of commerce was thus engaged in overt vitriol, Rockefeller himself opened a second, silent, front in the war on oil.

There were 26 competing refineries operating in Cleveland in 1872. Using the cash from his investors, he went to each of them offering a generous buyout offer. Presenting the details of Standard Oil's financial status and projections, he demonstrated that the others could either accept the buyout and live comfortably on the dividend-paying stock he offered, or they could be driven into bankruptcy.

His proposal was accepted by all but four competitors, each of whom was out of business and destitute by the end of the year.

In April 1872, less than four months into their agreement, the South Improvement Company charter was legally revoked by the State of Pennsylvania. This mollified the crowd demanding their pound of flesh.

However, Rockefeller’s quiet "Cleveland Massacre," as the refinery takeover became known, largely went unnoticed.

Rockefeller became the undisputed king of the oil industry in America.

Despite his aggressive strategies, Rockefeller maintained a focus on product quality. Standard Oil's kerosene was consistent and well-regarded, and the company's management was superior to most competitors.

Consumers loved it: The price of oil decreased by half.

What Rockefeller brought to the industry: Attention to product quality, strategic maneuvering, bold tactics and personal commitment at high risk. These combined to attract investment and secure customers.

A Busted Trust

Standard Oil Company became Standard Oil Trust in 1882. (Trust was a term for a combination of business enterprises operating as a single, very large-scale entity.)

The Sherman Antitrust Act was passed by Congress in 1890.

The rationale for Sherman was that large corporations could wield their power in ways to disadvantage smaller businesses, and that the consuming public might be harmed by the lack of competition. Under Sherman, anti-competitive practices did not necessarily have to be proven; the mere presence of a monopoly was proof enough that the trust should be broken up.

Hence the term “trust-buster.”

The U.S. brought suit against Standard Oil Trust in 1906, during Teddy Roosevelt’s administration, and in 1911, the company was ordered to divest itself of all major holdings.

John D. Rockefeller’s vision reigned for 40 years, and then was gone.

The Standard name remains today, alongside related entities Amoco, Mobil, Chevron, Exxon and British Petroleum. All either stemmed from, or absorbed divested assets of, Standard Oil Trust. Other spinoffs still alive today are Atlantic Richfield, Buckeye Pipeline, Pennzoil and Union Tank Car Company.

Murray Rothbard

About 30 years ago, on the subject of Standard Oil’s demise and John D. Rockefeller’s legal comeuppance, I listened to a set of lectures (on cassette tape) by Murray Rothbard, a professor from the Austrian School of Economics.

Never mind about the Austrians… that’s way outside our scope here. (Although it is fascinating, and relevant, and the subject may explain why inflation is eating up your income this year.)

To say that Rothbard was a cynic is something of an understatement. Deeply satisfying, he offered detailed and delightfully sarcastic explanations of the history of economics in the United States.

He maintained that the 1901 assassination of William McKinley (POTUS #25) was related to trustbusting in the Standard Oil case.

Here is how his argument went:

McKinley, Republican, was from Ohio. His Vice President, Roosevelt, Republican, was from New York. In those days, the President and VP were chosen individually by their parties’ convention. They were not political allies until the the convention put them on the same ticket.

At the time, claimed Rothbard, there was serious financial competition between John D. Rockefeller (Standard Oil, Ohio) and J. P. Morgan (Morgan Bank, New York). Per Rothbard, Rockefeller backed his guy McKinley (Ohio), and Morgan backed Roosevelt (New York).

Rockefeller had ambitions for global domination of the petroleum industry and the fabulous wealth it would generate. Morgan’s father had been the foremost money manager in London, while son J. P. had been his counterpart in New York. After the senior’s death, J. P. Morgan controlled empires of cash on both sides of the Atlantic.

McKinley, backed by Rockefeller, won the presidency. Teddy, backed by Morgan, had to settle for the VP slot.

And then McKinley was shot.

Teddy became President.

Rothbard (from my memory of his lecture): “Every time there is a murder in this country, the police leave no stone unturned, searching for means, motive and opportunity. Every time a President gets shot, it’s suddenly a lone nut with a gun, case closed!”

In plain language, Rothbard implied that Morgan would not accede to the loss of the presidential campaign, so the President was simply taken out of the way. And then, the new President — from Morgan’s own New York — initiated the antitrust case against Standard Oil, Morgan’s financial competitor.

Morgan profited from the Standard Oil breakup, and it was seen as a huge defeat for Rockefeller.

The breakup of Standard Oil did not occur until 1911, after Roosevelt was out of office, but the President at that time was William Howard Taft, Teddy’s hand-picked successor.

We will never know the truth of these machinations. And we may not want to learn it.

Theological Contemplations

2 Chronicles 31:21 Hezekiah did throughout Judah… what was good and right and faithful before the Lord his God. In everything that he undertook in the service of God’s temple and in obedience to the law and the commands, he sought his God and worked wholeheartedly. And so he prospered.

Love John D. Rockefeller, or hate him, he moved the price of oil down by 50% and put an essential, high-quality product within reach of most consumers. It was delivered at the promised price and on time. Coincidentally, fortunes were made for many thousands in the supply chain.

He lived his life with all his heart, and I cannot avoid the comparison with Hezekiah.

This does not mean Rockefeller was thoroughly pure in all his ways; there was a ruthless side. In the game he chose, it was a necessity.

Don’t think the Hezekiah comparison is a stretch; Hezekiah had his own problems, which showed up in Isaiah 39:3-8. We really don’t have time for that one now. Maybe later.

Meanwhile, the message would seem to be: Work your game with all your heart, but direct your steps in service to God, and in obedience to His commands.

Subscription Reminder

If you’re new here, welcome! Use the subscribe button below for a free subscription to The Alligator Blog. Your name is not required at this level, only your email, so that you may receive this indispensable trivia in your inbox regularly.

If your button says Upgrade, please click through if you think these missives are valuable and should be continued. Free merch with your annual subscription.

To quote a character whose name I cannot remember in George MacDonald’s Phantastes (Fantasies): “Now go, and do something worth doing!”

Curt

Share this post