Okay, look, there will be some arithmetic in this one. Let not your heart be troubled; we can get through this. It is a story of human suffering, shipwreck, scurvy, starvation, telescopes, the moons of Jupiter, some minor mathematics… and a pot of gold at the end. (Or not.)

In A.D. 1707, four English warships under the command of Sir Cloudesley Shovell were wrecked at St. Agnes Island off the southern coast of Great Britain. They foundered on the rocks one night purely because Sir Cloudesley could not ascertain his longitude and thus, while he had adequate charts, did not know where he was.

Latitudes Go Sideways

In point of fact, he did not know how far east or west of the murderous island he was. He knew perfectly well how far north or south he was, but the island lived unfortunately in two dimensions, not one.

From time immemorial sailors had been able to determine their latitude – how far north or south of the equator they were – by sighting the sun and computing its height above the horizon.

(Lest you think people “from time immemorial” were not as smart as us, consider the Egyptian pyramids and other ancient wonders. A pastor friend once pointed out that, from the perspective of a Christian worldview, the gene pool in the day of Adam and Eve was perfect: No blemishes or corruption or mutated white blood cells or leukemia or any of that. The advent of sin somehow introduced impurities into the DNA, but for many of the first generations, the pure inertia of pure creation held sway. The people would have been larger, stronger and more intellectually fit than we are. Take it or leave it; but that was his opinion.)

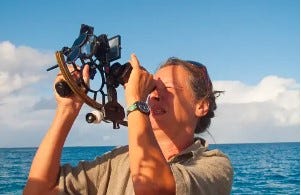

A sextant makes finding your latitude easy. Not fall-off-the-bed easy, but not clean-out-the-garage hard, either. You can find directions online, which, if you are planning to be adrift on a raft in an open sea with no wifi, it would be best to do ahead of time. (This looks like a fairly cool science experiment you can do in your back yard. Try it; take pics and send them to me. I’ll post them.)

But determining longitude – how far east or west of an arbitrary location you might be – is a different matter.

Longitudes Go Up and Down

Longitude lines are those which run vertically around the globe, from South Pole to North and back again in a giant metaphysical oval called a meridian. Think of an orange cut into slices.

The Earth is a ball – a squashed ball, but a ball nonetheless – and therefore the entire circumference, in degrees, is the circumference of a circle: 360 degrees. While we know this from science – and from pictures sent back from the Apollo missions – it validates the reliability of the Old Testament when we see passages like Isaiah 40:22 [God] sits enthroned above the circle of the earth…

The earth rotates on its axis, as we all learned in 7th grade science (or should have done). One full rotation takes 24 hours, give or take, but let’s call it good.

If it takes 24 hours to rotate 360 degrees, how many degrees has it moved in 1 hour? Class? Anyone? It would be of course 1/24 of 360, or 15 degrees.

Using that bit of mathematical magic, we can slice the orange that is the earth into 24 slices (or meridians), each 15 degrees wide. At the equator, where the circumference of the earth is about 24,000 miles, this means each meridian is about 1,000 miles wide. The farther north (or south) you are from the equator, the closer together the meridians become.

And now: Finding where you are on the globe with respect to the meridians requires you to know what time it is. Keep reading.

Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is?

As I remain stationary, the globe travels and carries me with it. After a theoretical hour of me reclining comfortably, say, in a chaise lounge on the deck of a custom Alfresco 110 yacht at anchor in the harbor at Singapore (which is on the equator), I have actually moved 15 degrees, but my relation to anything else on earth has not changed. I still know where I am.

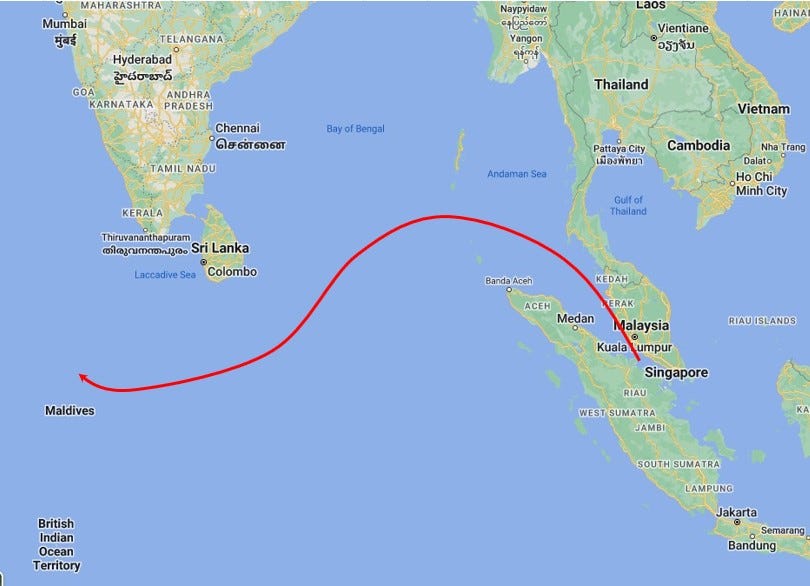

But if I sail that Alfresco for an hour out into the sea, heading northwest up the Malacca Straight and then turning left into the vastness of the Indian Ocean, I will have moved, and also the earth will have moved, and unless I have functioning nav aids, the Alfresco and I will be hopelessly lost.

But if I had a reference point on the earth, say a place like Greenwich, England, which for several hundred years has been established as a location on what we have arbitrarily designated the Prime Meridian, and if I could measure how far I was from that meridian, then I could establish my east-west location.

We have already discussed how to establish latitude, the north-south location.

So, the longitude: On the Alfresco, I know when high noon occurs, because (using the backyard science experiment from a previous paragraph, which you probably have not done yet) I can determine when the sun is at its zenith. If only I knew exactly what time it was back at Greenwich, I could simply say, “Look, it’s noon here, and it’s 7:06 AM in Greenwich, so I am 4 hours 54 minutes east of Greenwich, and because each hour is 15 degrees wide, I am (4.9 hours X 15 degrees = 73.5 degrees) at 73.5 degrees East Longitude.

Which puts me right at my destination: The Maldives Islands are at North Latitude 1.9772 and East Longitude 73.5361.

Important note here for those of you who participate in scavenger hunts and use smart phones to find your lat/long: Everything EAST of Greenwich is expressed as a positive longitude value, like +73.5361 (Maldives Islands). Everything WEST of Greenwich is expressed as a negative longitude value, like –87.6298 (Chicago). This is because when number lines were first created by God (or Archimedes, or Pythagoras, or Eucalyptus, or somebody), zero was in the center and everything to the right was plus, while everything to the left was minus. We can’t help it... that’s just the way it is. So, in America, all of our longitudes are minus numbers.

Voyage to the Pacific

This study of longitude was life-or-death to British mariners in the 18th century: How can we know what time it is in Greenwich, England? Dava Sobel, in her enlightening and highly readable Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time (Bloomsbury USA, 2007), describes a voyage from England to the Pacific Ocean. As I recall, it was about the year 1770.

The British fleet of a half dozen ships was separated in the storms of the Tierra Del Fuego (tip of South America), and only the flagship made it up into the Pacific. They reached the south latitude where they knew an island would allow them to re-supply. But in the featureless ocean, were they east or west of that island?

They had long run out of provisions, and without fresh fruit and vegetables, sailors were dying of scurvy.

The commander ordered the ship to sail west along the latitude. They did so for three days, found nothing, then turned around and sailed east, seeking their salvation. After recovering that three days of westing and continuing on east, they eventually, and unfortunately, sighted the tops of the Andes mountains.

The island was west of them. They turned around again. When they finally found the island, something like a third of the crew had succumbed to scurvy.

Where is Galileo when you really need him?

In the early 1600s, Galileo Galilei built a telescope and discovered that Jupiter was orbited by moons.

Who knew?

He could see four them, which turned out to be the largest of the 92 we now know: Io, Europa, Ganymede, Callisto. We earthlings observe them in a line across, like looking at a Frisbee edge-on. They seem to move closer to, or farther away from, their host planet, both to the left and right, as they orbit.

These moons have been the stuff of science fiction, as one of them is about the size of Earth (although probably much colder). Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey has astronaut Dave visiting one of those moons (Europa?) where the aliens are. Robert A. Heinlein’s Farmer in the Sky uses one of them as the destination for agrarian immigrants from an over-populated Earth.

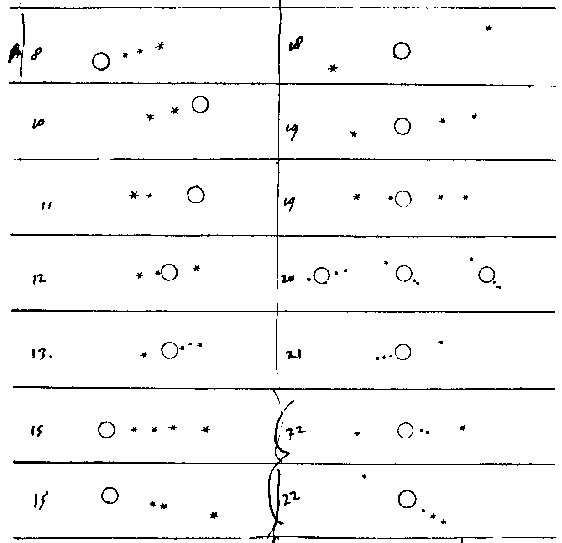

The orbits of Jupiter’s moons follow strict timelines, just as our own moon does. Galileo understood that measuring the distance of, say, Io from Jupiter, was a benchmark for time. Io would appear in exactly the same place again exactly 1.769 earth days, or 40.5 hours, later.

Using the exact moment when Io emerged from eclipse behind Jupiter (or from in front of it, hard to tell which, but its sudden appearance was virtually instantaneous) Galileo pegged that moment to his local time, which he ascertained by knowing how many hours his observation was from his local noon.

From that – and this is really tedious, so don’t try it at home – he attempted to construct a set of timetables to show what time it would be in Venice each and every time that Io thus emerged. After Galileo’s death, Gian Domenico Cassini published a set of reasonably accurate tables.

And voila! Wherever in the world we can observe Io emerging from eclipse, we know exactly what time it is – right now – in Venice. If we remembered to bring Cassini’s charts along. And if we ignore the 10 minutes lag time due to how slow light travels, but that’s a different story.

The problem, of course, is that this method does not solve the sailor’s problem.

Amateur Stargazer

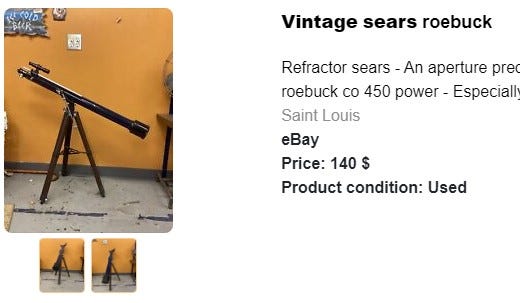

In about 1966, with great trepidation for fear of straining family resources, I asked Mom to buy me a telescope I saw in the Sears, Roebuck catalog. Not because of Galileo or longitudinal nightmares, but because the U.S. Space Race was all the rage and I wanted to look at stars and planets.

On crisp winter evenings when there was no moon, I would take the tripod-mounted 4-power device into the front yard and let it adjust to the cold for 10 minutes, allowing the fog to clear off the lens. Dad shut off the yard light for me, and, because we lived on a farm, there was little ambient light in the sky.

Jupiter could be easily identified. After several sessions of working the telescope, I found Jupiter’s moons. There were four of them visible. I had to use the high-power ocular lens rather than the standard lens; the aperture was tiny, and it was impractical to search the sky because the field of view was extremely limited. The planet had to be lined up first with the standard lens, then, without touching the telescope, I switched out the ocular. Getting Jupiter in sight was little more than pure luck, but on two or three different occasions I was able to see the four moons.

Seconds after I sighted them, they were gone, moving out of view as the earth turned.

But I did it with 1966 technology and a $50 telescope.

A better timepiece

Doing this from the deck of a ship using 1766 technology – at any price – was an impossibility. So, the British set up a competition: Who can build a chronometer that can sail around the world in all kinds of weather, in a saltwater environment, with never a stationary mount, and be accurate to within about 3 seconds per year?

The specification (I actually don’t remember how many seconds it could be off) was determined by the search area from a sailing ship’s crow’s nest. If the clock loses or gains time, the ship will be in the wrong place when the sailor looks for the island. A few miles error can sink the island below the horizon.

Pendulum clocks would not work because of the constant motion of the ship. The solution would have to be in springs, and the metallurgy of the day was barely up to the task. Inventor John Harrison won the competition, something like 20,000 pounds sterling (millions of dollars to us today) but of course he never saw the money. Because lawsuits.

But the technology persisted. By the dawn of the 19th century the marine chronometer was in widespread use. Two clocks were generally carried on board: One set at Greenwich Mean Time (which we now call something else, because we call most things something else now), and the other set to local time based on sun sightings.

In one of James Clavell’s novels, I think it was Tai-Pan (Atheneum, 1966), the neurotic captain of a sailing ship would not allow anyone to wind the clocks but himself. The chronometer became as important to the sailor as the horse was to the cavalryman.

And finally, Peter Pan

The plotline of the fantasy story that became a Disney sensation is primarily a sailor’s nightmare. The crocodile swallows the clock. Captain Hook must have the clock to find his way home, and now, because of the longitude problem, we know why. Hook’s future is thus forever entwined with the crocodile, which is both his mortal enemy and his only hope.

At the severe risk of over-thinking this (which is my natural state of things), I often consider who my mortal enemy is. I have concluded it is not the Devil; it is me.

The Apostle tells us: For I know that good itself does not dwell in me, that is, in my sinful nature. For I have the desire to do what is good, but I cannot carry it out. For I do not do the good I want to do, but the evil I do not want to do…. Romans 6:18-19

Like the unfortunate stranded Captain Hook, we, all of us who seek to follow Christ, are stranded strangers in a strange land. We seek to live in accordance with heavenly righteousness, and there are plenty of cultural pressures trying to squeeze us into some other mold. But our real enemy is the one within.

Pogo said it in 1970: We have met the enemy and he is us.

And yet, we find deliverance in this assurance: Who will rescue me from this body that is subject to death? Thanks be to God, who delivers me through Jesus Christ our Lord! Romans 6:24-25.

Have a good week! And know where you are, both physically and spiritually!

Curt

Share this post