August 30. 2023

First Things First

It’s a messy world. When I ran the truck in for A/C work on the hottest day of the year I found that the woman behind the counter, with the unlikely name of Tamizan, had a 25-year-old son with cancer.

That sort of made my A/C problem seem puny, and besides that, the “Tamizan” name was too good to ignore.

Tyler, who works construction, was diagnosed with some sort of cancer last fall… no actual diagnosis yet. But it has since gotten worse and has spread to colon, blood, lungs and liver. He is doing tests at KU Med this week and is scheduled for an M.D. Anderson visit in December.

See Tamizan’s Facebook page for his story at https://www.facebook.com/tami.knollenberg.

Tyler’s employer has been quite supportive, but nobody carries a cancer insurance rider for out-of-pocket expenses on a 20-something. The GoFundMe page targets $25,000. They are about halfway there.

Whatever you can do to assist will be greatly appreciated.

The 1880 Presidential Election

Why would I care about the 1880 presidential election?

Because there are lessons to be drawn from this story, and they have great implications for our current state of affairs.

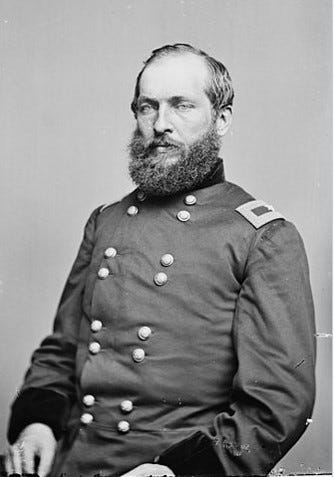

James Garfield came from a modest Ohio family, completed a college degree and joined the Yankee Army in the Civil War, eventually rising to the rank of Brigadier General. (Battles of Shiloh, Corinth, Chickamauga.) In 1862 he was elected to the U.S. House on the Republican ticket, and promoted by the Ohio state legislature to U.S. Senate in 1880.

Recall that in those days, prior to the 1913 adoption of the 17th Amendment, U.S. Senators were elected by state legislatures. And maybe they still should be, but for our present purposes that’s a rabbit trail.

Garfield’s big break for national prominence came later in 1880 at the Chicago Republican National Convention.

Incumbent Republican President Rutherford B. Hayes had been elected in 1876 in a bitter contest with Democrat Samuel Tilden. Election fraud and intimidation had been alleged — go figure — and Hayes was declared the winner amid much controversy and bitterness. He could not amass a following for a second term.

Former president U.S. Grant was an overwhelming force, and sought a third, non-consecutive, term, but many Republicans disliked the notion of repudiating George Washington’s self-imposed two-term limit and would not back him. There was also the widely understood financial scandal that had rocked Grant’s second term, and this produced a party led by the colorful and probably corrupt James G. Blaine of Maine who cried, “Anybody but Grant!”

“James G. Blaine, James G. Blaine; the continental liar from the State of Maine!” was the Democratic slogan in opposition to Blaine 4 years later, but that’s another rabbit trail.

Today we would call Blaine’s people never-Granters.

At the Republican convention, Garfield rose to nominate John Sherman of Ohio. The convention deadlocked on Sherman and Blaine. After 33 ballots over the next two days, the conflict remained intractable. On the 34th ballot, the Wisconsin delegation offered 16 surprise votes for Garfield, who was not even running.

Two ballots later, Garfield won enough delegates to make him the party nominee. He had not sought it, had never even considered it was possible, and his wife was not particularly pleased. But the party called, and he answered.

The General Election

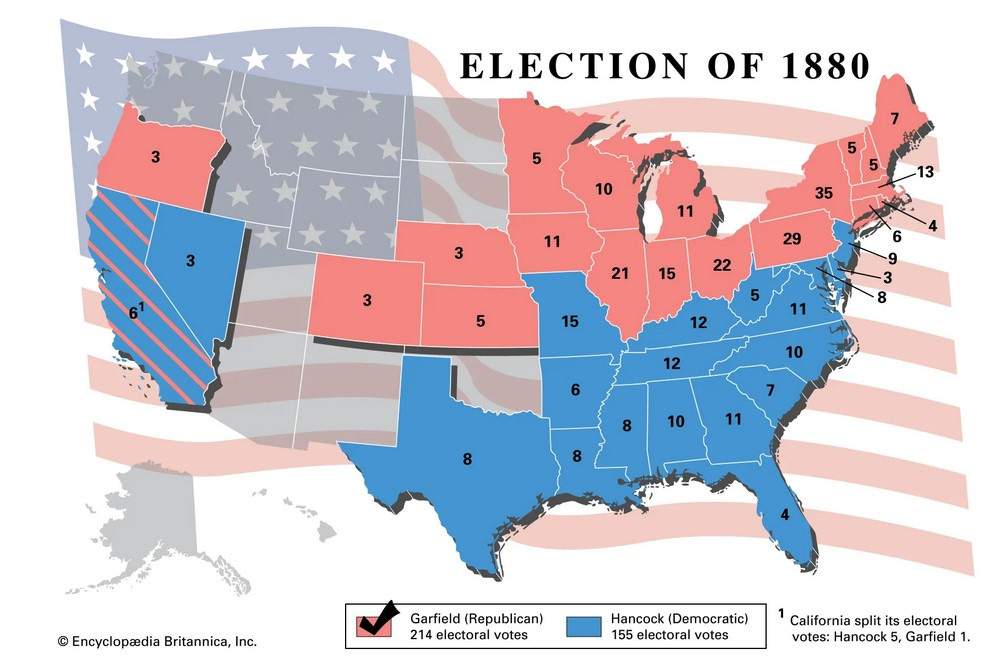

Republican James A. Garfield soundly defeated Democrat Winfield Scott Hancock (commander of Union forces at Gettysburg) in the Electoral College, but the popular contest awarded the winner a margin of less than 10,000 votes.

Part of Garfield’s campaign message was his opposition to what he saw as “an insatiable lust for office and patronage” on the part of the Democrats. The federal government was growing (when has it NOT been growing?) and he was solidly in favor of a Civil Service system that offered jobs for merit rather than personal favor.

This would prove his undoing, even as he won the national election.

Chester A. Arthur of Vermont was of an Irish immigrant family and son of a Baptist preacher. He was a compromise candidate for Vice President in 1880; at that time the President and Vice President were chosen separately for their party’s presidential ticket.

This meant their political platforms did not necessarily align, and the case of Garfield and Arthur highlighted this like no other has.

Garfield was opposed to federal government jobs being given as favors; the issue was called “patronage”, and he was strongly in opposition.

Arthur believed the chief executive was entitled to appoint whom he wanted in government positions, because the people had voted for him.

The two philosophies could not be reconciled.

The Assassination of James A. Garfield

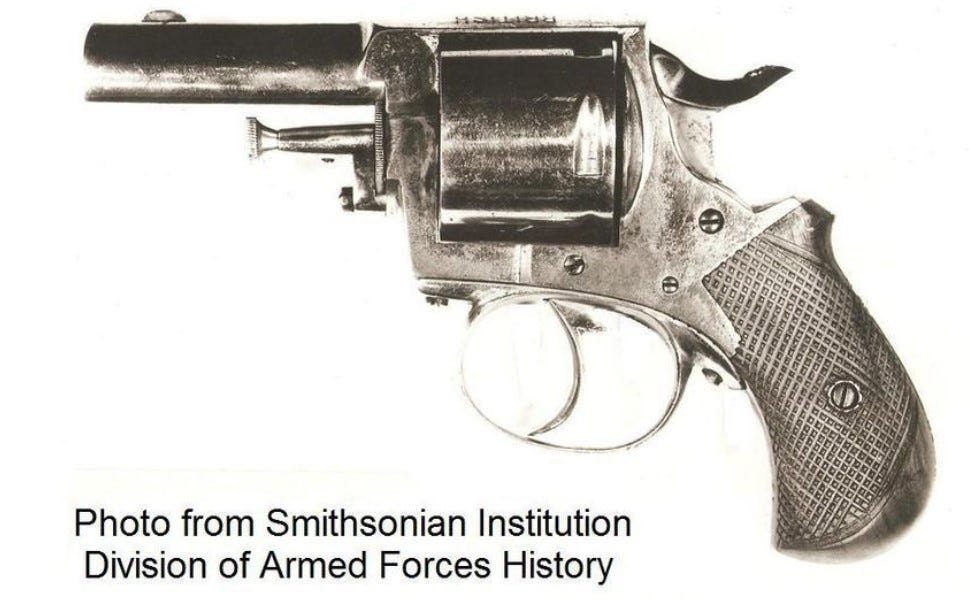

Enter Charles J. Guiteau, an emotionally disturbed 39-year-old in Washington, D.C., who had purchased a .44 British Bulldog revolver because he believed it would make an impressive museum display piece after he used it to murder the president.

On a July morning in 1881, four months after the inauguration of POTUS #20, President Garfield walked to a train station with his Secretary of State (the above-named James G. Blaine) and Garfield’s two teenaged sons.

Two shots struck the president in the back from virtually point blank range.

One of the bullets lodged near the pancreas. It was not fatal until surgeons with unsterilized hands launched multiple operations to probe for the bullet.

Painfully, James Garfield bravely clung to life, telling his sons, “The upper story is alright. It is only the hull that was damaged.”

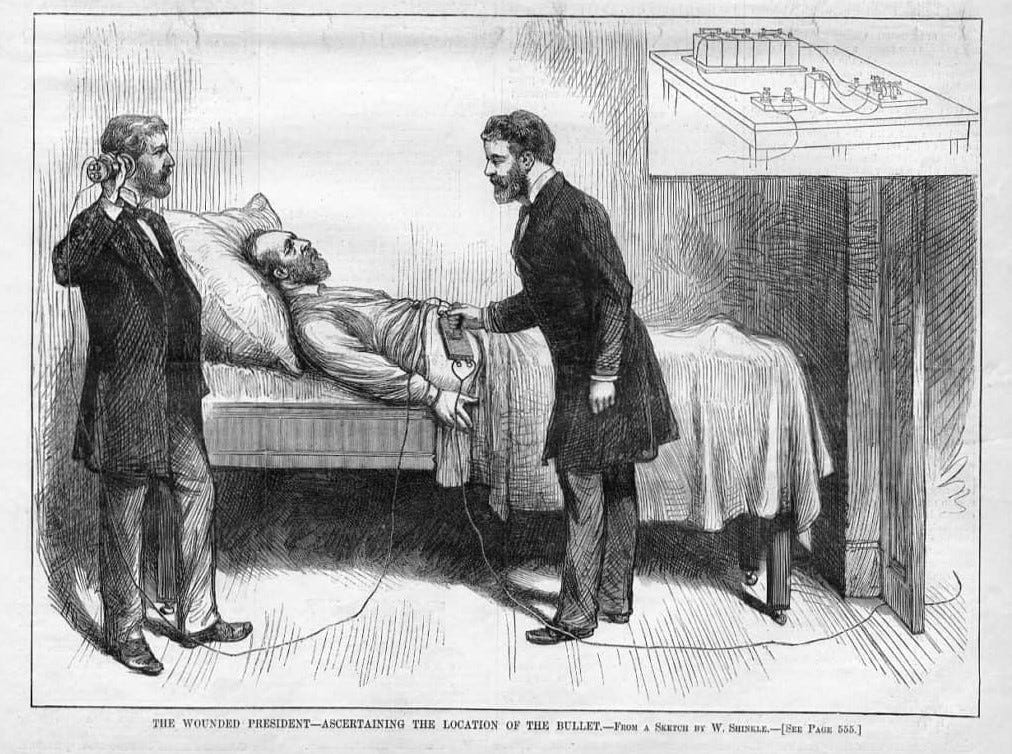

After weeks of ineffective treatment, doctors allowed young inventor Alexander Graham Bell to try to find the stubborn bullet with his new-fangled metal detector. Bell was only allowed to search the right side of the President’s body, where the bullet had entered. No one knew it had ricocheted inside and was several inches away, on the left side.

Adding to Bell’s exploration difficulties was the bed on which Garfield lay. The mattress was a new invention itself, with unheard-of inner coil steel springs. Bell apparently had no idea why the metal detector, so reliable in lab experiments, gave such puzzling results in the first real-world application.

The bullet remained elusive, and President Garfield died after three excruciating months, September 19, 1881.

Months later, the assassin’s legal defense boiled down to, “Yes, I shot the President, but it was the doctors who killed him”.

The mentally disturbed Charles Giteau was found to have initially been an ardent supporter of Garfield’s presidency. He had written a speech supporting the campaign. Although it was virtually ignored, Giteau convinced himself it had been key to Garfield’s success.

Just after the inauguration, Giteau had asked for and been granted an interview with the new president. At this meeting he asked to be made U.S. Ambassador to France as compensation for his political support. The request was denied.

It may seem odd that Giteau would ask patronage — a favored political appointment — from the very man who had so clearly asserted that he would not back patronage appointments, but that nuance was lost on Giteau.

Giteau became bitter and obsessed, and later admitted that one night in his ravaged dreams, he believed God had inspired him to kill the president.

Charles Giteau was tried by jury, convicted of the assassination, and hanged on June 30, 1882, almost exactly one year after the fatal shots were fired.

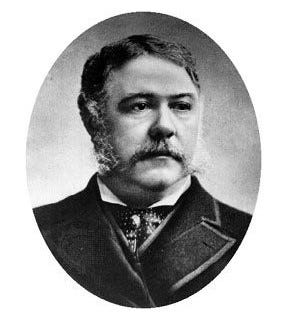

Chester A. Arthur

The Vice President was sworn in.

Arthur was firmly on the other side of the patronage issue from Garfield, but all that changed with the passing of the president.

Arthur switched sides and championed civil service reform, as Garfield would have wanted. He signed the Pendleton Civil Service Act in 1883, permanently putting an end to political patronage.

Or at least, as permanent as anything is in this country.

Why did Chester Arthur suddenly take on his predecessor’s burden and destroy the very system of political favoritism that had seen Arthur himself rise to the top?

We can only guess. Arthur himself apparently ordered the destruction of his personal papers after his presidency, so his motivations remain forever unknown. But there are indications.

It is quite probable that Arthur saw himself in the role of the reluctant hero, thrust into his position by circumstances beyond his control. He did not deserve the presidency, but the system that put him there required that he serve the people.

And the people had elected James Garfield, who had stood against patronage. Whatever Chester Arthur’s own convictions on the issue, he carried out Garfield’s agenda.

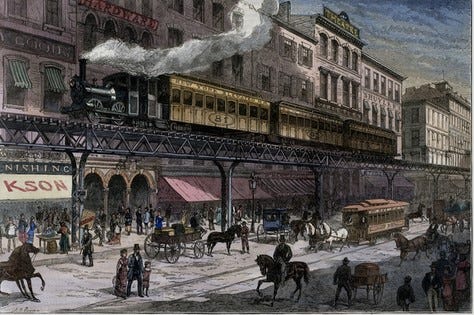

As a young attorney in New York City, Arthur had taken on a civil rights case eerily similar to Rosa Parks’ a hundred years later. Elizabeth Jennings Graham, a black woman late for church one morning, had stepped onto a crowded streetcar meant for whites. She refused to leave when ordered off. She was arrested and charged.

Chester Arthur, 24 years old, defended her case, won, and started a chain of events that led to the desegregation of the New York City public transportation system.

In both this, and later in his presidential veto of Chinese exclusion legislation — a bill that would have prohibited Chinese immigrants from applying for U.S. citizenship — we see a man with a moral compass.

i would like to think that Chester Arthur might have agreed that “We do not always get to choose the trials we face, only how we face them.”

Verse for the Week

Romans 13:1 Every person is to be subject to the governing authorities. For there is no authority except from God, and those which exist are established by God. Therefore whoever resists authority has opposed the ordinance of God… [NASB]

It may be a stretch, but I think it quite likely that Chet Arthur believed he owed the American voters an obligation to carry out the agenda of the man they had elected. The issues of government did not belong to him, they belonged to the American people, and he would see the reforms they voted for made into law.

Whether that was in his mind or not cannot be discovered, but that is exactly how it came out.

By all accounts, Chester Arthur’s presidency was unremarkable, except for the one unavoidable truth that he put the interests of the people ahead of his own. That is integrity.

We could probably do with a little more of that.

Have a good week!

Curt

Share this post