I have been listening to the audio version of Killers of the Flower Moon (Doubleday, 2017), a non-fiction murder story about Osage Indians who mysteriously began to die after oil was discovered on tribal land in Oklahoma, c. 1920.

This led me to contemplate how these Native Americans wound up on a reservation granted by Great White Father instead of wide-open buffalo lands. That, as you might guess, eventually landed me in Andrew Jackson’s lap a hundred years earlier. I began to review “the Indian question” once again.

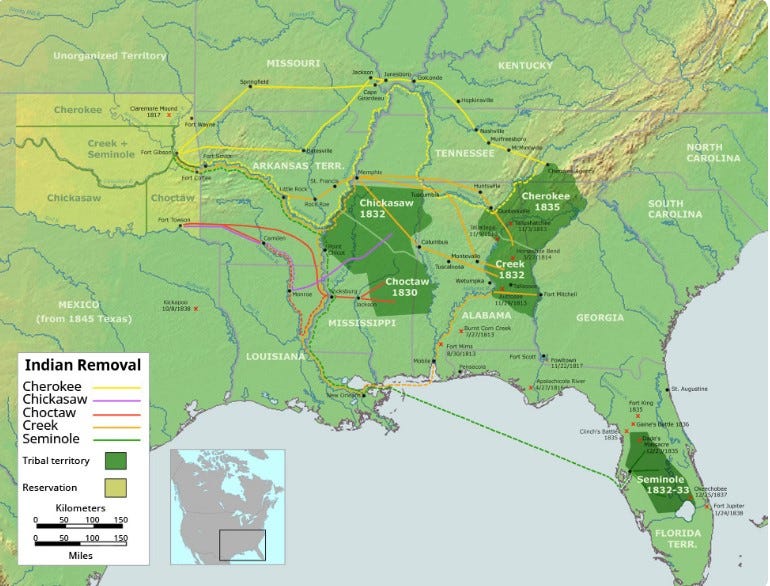

As President, Jackson pushed for and ultimately signed the Indian Removal Act of 1830, ordering the resettlement of the “Five Civilized Tribes” from Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi and Florida to territory that would become Oklahoma.

Who was Andrew Jackson?

A son of poor Irish immigrants, Jackson had fought in the Revolutionary War and 30 years later was a Major General, U.S. Army, at time when the British, fresh from their 1812 victory over Napoleon at Waterloo, had declared war on the young United States. British troops had torched Washington D.C., forced President James Madison’s administration to flee the capitol, attempted to invade Baltimore, and laid plans to take back the Mississippi River. They aimed to do this by controlling the important port of New Orleans.

Andrew Jackson, “Old Hickory,” stood in opposition. In flagrant disregard for civil procedures, Jackson declared martial law in New Orleans, ordered every able-bodied man to join his scratch defense and outfitted them with weapons confiscated from the citizenry.

Thousands of men bolstered the ranks of his regular army: Local militia, Kentucky and Tennessee frontiersmen, Louisiana aristocrats, slaves, free blacks, Choctaw Indians and the notorious Jean LaFitte’s pirates. Ultimately, 4,500 Americans made up a ragtag band of resistance.

A “Jackson Line” was hurriedly prepared along a canal south of town. Slaves widened the canal, added a trench and used the dirt to throw up 10-foot-high breastworks behind which Jackson placed his field artillery.

When 10,000 British regulars made their frontal attack, they were lacerated by cannon grape shot and the deliberate, aimed fire of woodsmen who could hit a mark hundreds of yards away. The British general and 7 colonels were killed along with 2,000 redcoats in a strange land far from home.

U.S. losses were less than 100 killed. The populist general, now wildly and nationally popular, would become the 7th President of the United States 6 years later.

Johnny Horton popularized the victory — as overwhelming as it was unexpected — in his 1959 single “The Battle of New Orleans.”

The battle, of course, was unnecessary, as the Treaty of Ghent had ended the war a month earlier. In those days, international news traveled no faster than the speed of a sailing ship.

On to the Presidency

Andrew Jackson won election in 1828, riding the wave of “the common man,” the assertion that American men are self-made men, owing nothing to status or inheritance.

During his presidency, the franchise (right to vote) was extended to white males who were not property owners; he endorsed Manifest Destiny, that philosophy that saw America’s rightful place among nations as extending from the Atlantic to the Pacific; and he opened the deep south to white immigration at the expense of indigenous native tribes.

Cotton Becomes King

European demand for cotton exploded in about 1820, brought about by the development of the cotton gin some 30 years earlier. Cotton was lighter and more comfortable than wool and thus in great demand. The American deep south, particularly Mississippi, offered ideal agricultural conditions for growing cotton, and so began a huge wave of white immigration from north to south.

But the Indians were in the way.

Five tribes, the so-called “Five Civilized Tribes,” Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw and Seminole, inhabited as many states in that region. Imitating whites, these learned agriculture, they domesticated animals for food and leather, they wore European-style clothing and sent their children to learn English at missionary schools. The Cherokee even wrote a constitution specifying a bicameral legislature with three branches of government.

In a word, they assimilated.

Treaties were struck, offering cash payment for Indian lands. The tribes were divided over whether to sell their land, and there was much confusion over whether treaties would be honored.

Meanwhile, the flood of white immigrants, hungry for the wealth the land would bring, could not be stopped. Skirmishes developed; many on both sides were killed. The U.S. Army was enlisted to bring peace, which meant making war against the Indians. General Jackson, because of his position and reputation, was an early leader in this effort.

The 1830s were marked by Indian uprisings and bloodshed from Mississippi to Florida.

Jackson and others, particularly in the new Democrat Party, began to speak of removal. Their solution to the conflict, they believed, lay in persuading the native population to give up their traditional lands and move west where there was less pressure from white migration.

Persuasion gave way to enforced resettlement. Opposition to what became a federal government initiative arose in both the U.S. House and Senate.

In 1830 the Indian Removal Act was signed by President Andrew Jackson, having passed the Congress amid great contention by razor-thin margins.

The Trail of Tears

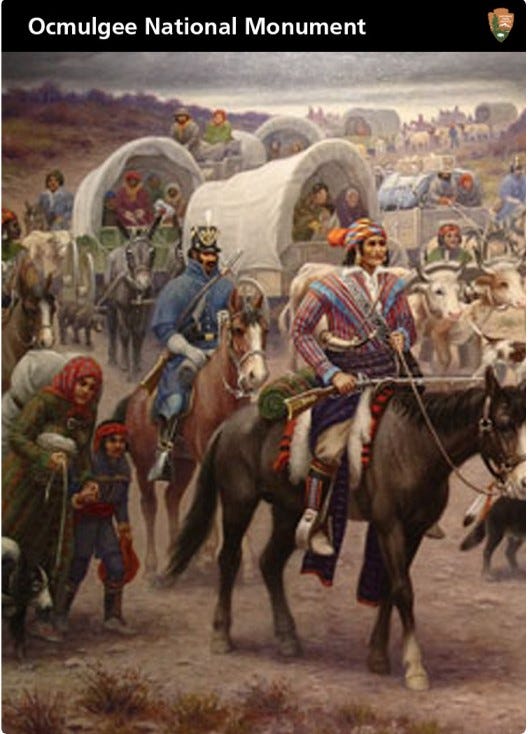

Over a decade, tens of thousands of once-peaceful, civilized native Americans were forced west. Oftentimes, wagon-loads of supplies promised for their journeys never arrived. Thousands died on the trail from malnutrition and unaccustomed winter weather. Once in the new land, thousands more fell prey to cholera, malaria, smallpox and influenza.

Alexis de Tocqueville was an eye-witness to an especially poignant scene at modern-day Memphis, as Choctaws made to cross the partially frozen Mississippi River:

The Indians had their families with them, and they brought in the train the wounded and the sick, with children newly born, and old men upon the verge of death. They possessed neither tents nor wagons… I saw them embark to pass the mighty river, and never will that solemn spectacle fade from my remembrance. No cry, no sob was heard among the assembled crowd, all were silent. Their calamites were of ancient date, and they knew them to be irremediable. The Indians had all stepped into the bark which was to carry them across, but their dogs remained upon the bank. As soon as these animals perceived that their masters were finally leaving the shore, they set up a dismal howl, and, plunging all together into the icy waters of the Mississippi, they swam after the boat.

Jackson Defies SCOTUS

There were two lawsuits during this time that made their way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The state of Georgia in 1828 enacted laws clarifying that Cherokee Indians, being a separate nation, did not enjoy rights as citizens of Georgia, and authorizing forced removal of tribal members from the state. The Cherokee resisted, referring to treaties negotiated with the U.S. government and pointing out that such treaties effectively acknowledged them as an independent nation. They appealed to the Supreme Court in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1830).

The Court found there was a duality involved: The Cherokee were indeed a standalone nation, but as they existed within the state of Georgia, they were dependent upon that state and were therefore subject to its laws. Therefore, the tribe did not meet the definition of a “foreign nation,” and could not fall under the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court.

The case was dismissed.

Another Georgia law passed in 1830 required citizens to be licensed by the state in order to take up residence inside the Cherokee Nation. This was perhaps a targeted rebuke of missionaries who taught English to the children and were known to resist the state’s removal of the tribe.

Missionary Samuel Austin Worcester was arrested, tried, convicted and imprisoned for violating the law. When Worcester v. Georgia reached the U.S. Supreme Court, the Court found that, because the Nation was indeed separate from, although existing within the boundaries of, Georgia, the license law regarding residence within the Nation was unconstitutional and must be overturned.

it fell to the Executive Branch to order the overturn of the law and to release the missionary.

Jackson disagreed, perhaps believing that the Constitution was flexible enough to allow thoughtful actors to go outside the law when the survival of the nation merited it. In any event, he let the Georgia law stand and Mr. Worcester remain in prison, and the President uttered the cynical (and perhaps apocryphal) statement, directed at the Chief Justice, for which Jackson became famous: “John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it.”

Actions Have Consequences

Jackson has been held aloft by some who decry the overly intrusive role the Supreme Court has played in politics. We would like to say this is a new development, but in fact it started in 1803 during Jefferson’s first term as president with the famous (or infamous) Marbury v. Madison decision. In that case, the Court declared a law passed by Congress unconstitutional, and thus established itself as a branch of government with power equal to both the legislative and the executive.

This rationale was based on a reading of the Federalist papers, which argued strongly for each of the three branches holding the others in check.

So… what of Jackson and the forced removal of the Indians?

On the one hand, the nation was growing, commercial progress was an unstoppable force, and the rich southern lands were the only right place for cotton to grow. On the other, the five tribes in question — unlike others farther west — were largely on a path to assimilation.

It falls to leaders to find a way to solve problems that have no solutions. There might have been no good solution to this conflict, but a review of the literature indicates there was not much effort to find one.

Perhaps trade and commerce, and leasing lands for agricultural production, could have been pursued. I don’t know; I wasn’t there.

As Killers of the Flower Moon makes clear, an Osage Indian tribal leader in the 1890s insisted on the natives obtaining mineral rights to their land when it was granted by treaty. That paved the way for unforeseen prosperity and cooperation in the next decades when oil was discovered. Marred by murder, to be sure, but that outside-the-law exception proves the value of the legal arrangement.

On this matter, I have to come down on the side of the Creeks and Cherokees. If nothing else, the sheer body count resulting from forced removal argues for a third way.

Honestly reviewed, it is a chapter of our history that shows the wisdom of Jesus’ words related to consequences of actions: You will know them by their fruits.

Verse for the Week

Proverbs 14:12 There is a way that appears to be right, but in the end it leads to death.

The question that convicts conscience today is: What action can I take that will make life better for someone else? Contrarily, what action is occurring in my sphere of influence that takes away quality of life, or even life itself?

At the individual level, what resources do I have that can be used to show a better way?

To help you with this (and to be be crassly self-serving) order a copy of Alligator Wrestling in the Cancer Ward, or a ceramic mug that says, for example, “The Cancer Ward, where heroes serve,” and give it as a gift to someone appropriate.

Enjoy your week! Curt

Share this post