October 11, 2023

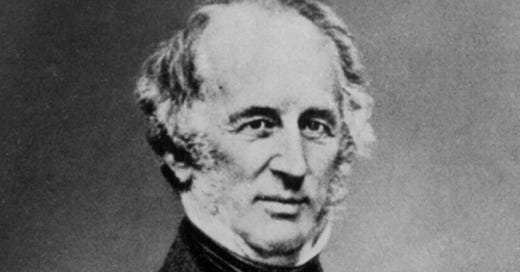

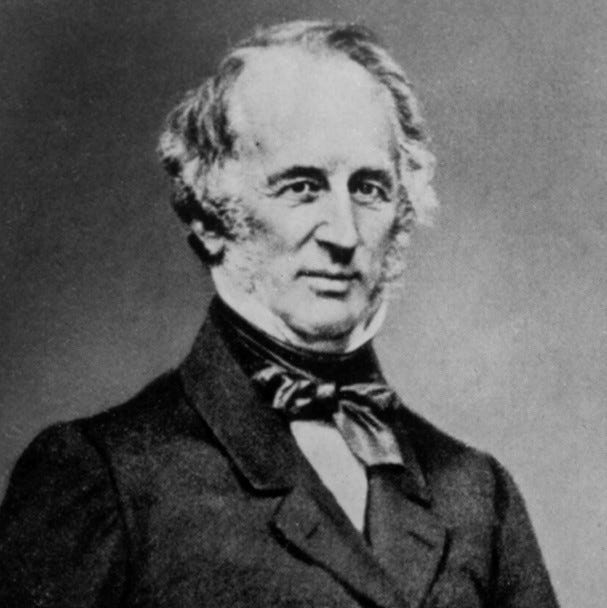

Like most of the titans of the American Gilded Age, Cornelius Vanderbilt worked wickedly hard, putting his peers and most adults to shame. Where others saw obstacles, he saw opportunity.

All his life (1796 - 1877) he was motivated by a drive for money, and he was astonishingly good at collecting it and using it. He had his own moral code, which was something along the lines of: This is a rough game. If you’re going to take the field, get ready to take the hits.

Vanderbilt was honest, fair, direct and ruthless.

From his humble beginnings on Staten Island, he helped his father ferry cargo across the harbor into New York City. At 16, his mother loaned him $100, a princely sum, to purchase his own boat. She was quite the negotiator in her own right (maybe he inherited something from her); the condition for the loan, besides paying it back, was that he must clear rocks from a field, no doubt for farming purposes.

He agreed, borrowed the money, and then discovered the rock-clearing was too much for him. He talked friends into doing the work and rewarded them with free rides on his boat, which is vaguely reminiscent of Tom Sawyer whitewashing the fence.

One wonders if Samuel Clemens knew the story.

Carrying cargo, Vanderbilt was able to repay Mom.

War of 1812

Fortuitously for young Vanderbilt, the British invaded about the time he launched his career. There is rarely anything better for business than a convenient war.

U.S. troops were garrisoned in New York and required supplies. The teenage Vanderbilt had already built something of a reputation for dependability, and he obtained contracts. This led to ferrying troops, which, after the hostilities were over, led to ferrying passengers.

Steam power became the thing, and Vanderbilt, joining with business partner Thomas Gibbons in 1818, applied himself to the new technology. Eventually, as he built his fleet through reinvesting profits, Vanderbilt became known as The Commodore.

The inventor of steam-power for river boats was Robert Fulton, which we all know from 9th grade American History.

What I do not recall learning then, was that Fulton had joined with Robert Livingston, a signer of the Declaration, to establish a steamboat ferry business on the Hudson river. Favorable state laws guaranteed them a monopoly on passenger traffic.

The upstart Vanderbilt sued, and the eventual Gibbons V. Ogden Supreme Court decision came down in Vanderbilt’s favor in 1824, establishing precedents for interstate commerce.

Continuing with his business partner, Vanderbilt began legally plying the Hudson from New York City to Brunswick, New Jersey, with passenger traffic. He expanded into a hotel property on the Jersey side and his wife ran it for him, along with managing the first of the 13 children she would eventually give him.

By 1829, The Commodore had sold his interest to Gibbons and used the proceeds to finance larger and more ambitious steamship routes. He served other destinations throughout New England and to Long Island.

He added more ships, and reduced the rates he charged to a point where new competitors found it unprofitable and left the business.

Vanderbilt apparently learned an early lesson: Don’t rely on the law to protect your business, as Fulton and Livingston had attempted. Instead, rely on your business to protect your business, by offering quality services at affordable prices. Operate the business in such a lean manner that others cannot compete effectively.

The Commodore stumbled onto an interesting method for success: Either drive your competitors out of their business, or make it financially attractive for them to purchase yours. He did both.

California Gold Rush

The U.S. war with Mexico (1846-1848) was followed by the California Gold Rush (1849). When the Sutter’s Mill business came about, easterners began flooding toward California. Twenty years prior to the first transcontinental railroad, the land route across Panama was used by most. Vanderbilt looked for a shorter passage — and one that was his, not someone else’s.

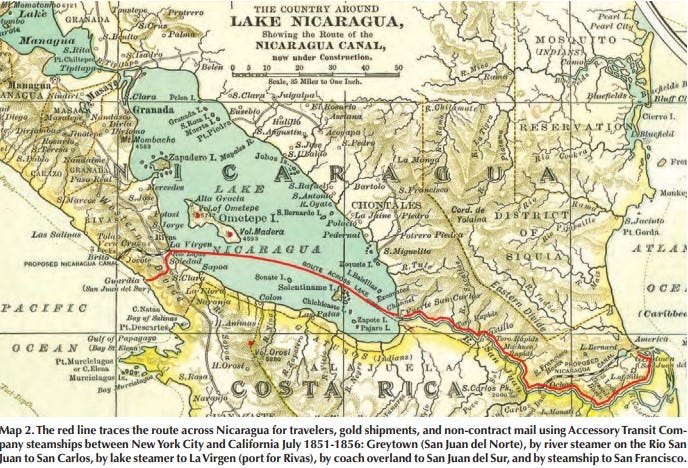

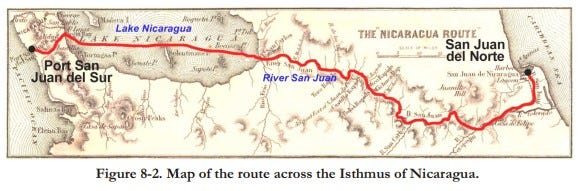

With a handful of American investors behind him, Vanderbilt signed a treaty with the government of Nicaragua to establish a land crossing for passengers that his Atlantic Steamship Line would deliver to Greytown, on the eastern shore of that Central American republic. His Accessory Transit Company would take passengers across the isthmus to the Pacific by canoe, steamship and carriage.

The entire transit through the Nicaragua passage was overall 500 miles shorter than New York to California by means of the Panama route. Beginning in 1852, about 24,000 passengers per year passed across Nicaragua in this way.

Plans were made for a canal, but due to events beyond even Vanderbilt’s control, were never executed.

Banana Republics

By 1855, the Nicaragua route was in trouble because of political unrest in that country. There was some minor flap with an American adventurer, William Walker, who formed a private army to invade Nicaragua and cancelled Vanderbilt’s contract.

Vanderbilt, never one to back down from a conflict, came up with a simple, bold plan: He hired Costa Rica to declare war on Walker, and Walker was ultimately driven out of Nicaragua. A new Nicaraguan government was formed, but that one also repudiated the relationship with Vanderbilt, accusing the American of having taken advantage of their people, and signed a new treaty with the U.S.

This obviated the relationship Vanderbilt believed should still be in force.

The Commodore sent his son-in-law to straighten things out. This was perhaps an early example of plausible deniability.

There is no telling what steps D.B. Allen took to reestablish Vanderbilt’s position, but given the players, I would be very surprised if it did not involve considerable cash quietly applied at the right places.

But admittedly, that is conjecture on my part.

At any rate, Vanderbilt regained control of the land passage. Then, having decisively won the battle, he concluded Central America was an unpredictable place to do business.

Competitors wanted his route and offered to buy him out for $40,000 per month. He took the money and turned his attention instead to the U.S. railroad business.

I find it instructive that Vanderbilt was determined not to leave Central America until it was clear he had won the conflict. The proof of his win was the monthly passive income.

The Commodore was not a man accustomed to losing.

This whole Nicaraguan Affair would make a great movie, or a streaming series. Steamships, jungle passages, gold seekers, business double-crossers, insurrectionists, armed adventurers, political deals, unlimited funding, invading armies, bribery, international intrigue.

I am woefully unfamiliar with the new breed of Hollywood A-listers, but from an earlier era I could see Timothy Dalton (Centennial, The Rocketeer, James Bond) as Vanderbilt, a young Brad Pitt as son-in-law D.B. Allen.

Somebody write the screenplay, please!

Railroads

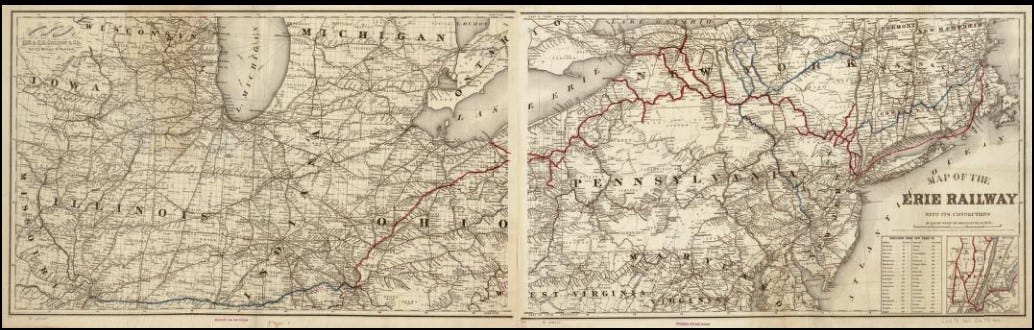

In the 1850s The Commodore began investing in U.S. railroads in a serious way. He served on the boards of the Erie Railway, the Central of New Jersey, the Hartford & New Haven, and the New York & Harlem.

Beginning about 1868, Vanderbilt sought control of the Erie Railway. Unfortunately for The Commodore, other quite unscrupulous investors wanted it at the same time.

Jay Gould had purchased a strong position in Erie for cents on the dollar, using profits from earlier questionable trades in other stocks, and in 1867 had worked his way into a directorship. Gould partnered with Daniel Drew and “Diamond” Jim Fisk.

Gould’s name was associated with many shady financial schemes in the post-Civil War era, including his abortive effort to corner the gold market. That unfortunate escapade resulted in the Black Friday stock market crash in 1869.

Later, Gould not only squeezed investors’ money from the Erie Railroad, but in other ventures he did the same to the Union Pacific, the Missouri Pacific, Western Union Telegraph, the New York World newspaper and the Manhattan Elevated Railroad.

Back to The Commodore

Vanderbilt wanted control of the Erie Railroad for its natural position connecting New York to Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and Ohio by way of Lake Erie stations. Recognizing this, Daniel Drew, a partner of Gould and Fisk, printed and distributed forged Erie Rail stock certificates.

The Erie Railroad War was on.

Vanderbilt’s purchasing spree encountered the fake stocks. He continued to invest, and eventually realized his ownership position had failed to increase commensurate with his investment.

Legal action ensued, and, colored with much bribery and corruption involving payoffs to legislators, law enforcement officers and judges, Gould and Fisk eventually were forced to flee New York and remove themselves to New Jersey.

The sort of illicit business they had conducted was only a state crime, not federal.

They travelled to New Jersey in a carriage with $6 million of investors’ cash, stuffed into bags, most of it belonging to Cornelius Vanderbilt.

Within a year, legal and legislative wranglings brought the Erie Railroad War to an end. Investors, including Vanderbilt, had lost millions. Drew, Gould and Fisk had pocketed the proceeds and were protected by corrupt officials who let the matter drop.

Vanderbilt sold his worthless Erie stock and, in much the same manner as he had departed Nicaragua, left Erie to its own devices.

I find this aspect of Vanderbilt’s life strangely unfulfilling. After a lead-up like this, I would suspect a suspicious house fire or an untimely accident befalling Gould and Company, but that never happened. They went on their way, more or less, and Vanderbilt apparently took no direct action against them.

Which tells me that The Commodore operated consistently within his worldview: Use your own energy, collect legal profits with outrageous boldness, use the money to accomplish what will benefit you, and do it all within the social and legal framework of your time. Stay in your lane and resist the distractions of deals that simply won’t work.

But he did get the money back.

Later, The Commodore negotiated a private settlement with Drew, who had, perhaps predictably, also been swindled by Gould and Fisk, who were themselves swindled in turn by the English con artist Lord Gordon-Gordon.

Vanderbilt recovered his cash and let Drew have the Erie Railroad.

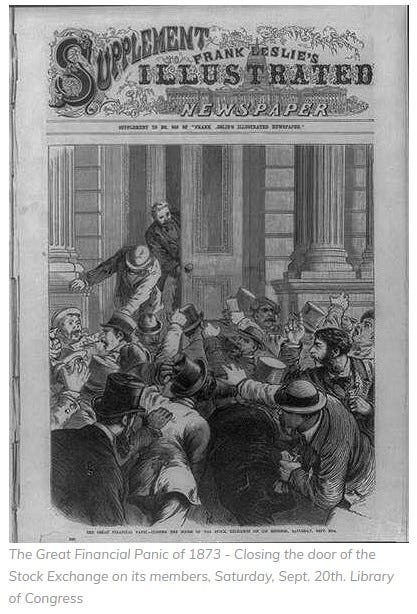

For Drew, that lasted about two years until he declared bankruptcy in the Panic of 1873.

Such was life in the fast lane in the time before market regulation.

New York Investments

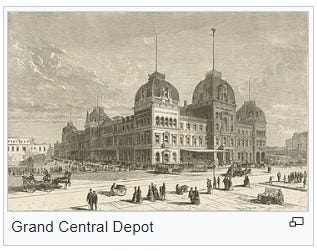

The New York & Harlem Railroad investment proved to be one of Cornelius Vanderbilt’s signal victories. He had taken an ownership position in it as early as 1864. Although unprofitable at the outset, it was the only rail line to serve midtown Manhattan. Recognizing the strategic value, Vanderbilt constructed what would become a monument to himself, The Grand Central Depot on 42nd Street, far outside the city center.

He suffered considerable criticism for the folly of putting a fortune into a site that no one visited, but Vanderbilt seemed have his eye on investment rather than public opinion.

The new terminal boasted the largest interior space in North America, accommodating 12 tracks and 150 cars. It was home to restaurants, retail shopping, a billiards room and its own police station.

Connections to horse-drawn street cars afforded transport to lower Manhattan.

From the beginning, steam locomotive traffic in upper Manhattan, even though sparsely populated, was a problem. In a single two-week period, 7 people were killed in crossing accidents.

This is generally bad for business.

Typically, Vanderbilt had a solution that involved applying lots of money. Cash was his weapon, he had plenty of it, and he know how to use it. He proposed physically sinking the rail line by several feet and providing bridges over the top.

This was not altruistic; it was not an apology. The Commodore probably did not mourn the loss of life or even feel responsible. But it was his track and his train that had done the killing, even if the victims should have known better.

Providing a safe way to get across the tracks was merely a responsible business decision.

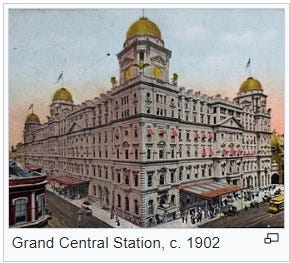

Early in the following century, this led to entirely covering 4th, 5th and Park Avenues to make them suitable for above-grade vehicle traffic. By 1902, steam was given over to electric power, other investors were spurred to lay plans, and the New York City underground subway system was born.

Between 1869 and 1900, the Grand Central Depot turned into Grand Central Terminal. Clever people do not call it “Grand Central Station,” because a station is merely one stop on a rail line. Grand Central Terminal at 42nd Street is the terminus for each of the lines it serves.

Pre-COVID, Grand Central Terminal handled 750,000 travelers per day. On a few occasions, I have been numbered among them.

How he Made His Millions

Basically, he drove others out of business.

From the early days of his shipping business he had pursued a strategy of operating with great efficiency and at low cost, owing to his near-fanatical personal energy. He was thus able to reduce his prices to a level where competitors could not be profitable.

On more than one occasion, this led to being bought out by those very competitors. He did this to his steamboat partner Thomas Gibbons in 1826; to the Hudson Steamboat Association in the 1830s, to the Nicaraguans in 1852, and to the New York Central Railroad in 1864.

Quasi-Religion at the End

Cornelius Vanderbilt is known as much for his ill treatment of family, wives and business partners as for his philanthropy and millions in personal wealth.

He despised the fact that he did not have more sons to whom he could leave his business empire. Of three boys, one — the most promising from a business acumen perspective — died of illness about age 20, and another Cornelius himself committed to an insane asylum on two different occasions.

Taken ill by intestinal, stomach and heart disorders, and perhaps also syphilis, Vanderbilt was confined to bed for several months prior to a painful death in January 1877. He left a $90 million estate in a lop-sided testament, awarding most to his remaining son and mere pittances to his daughters.

The will was tied up in court for years, the aggrieved parties pointing out that The Commodore had hired spiritual mediums to consult with him prior to his death.

There is much more to that aspect of the story, which turns out to be more tawdry than spiritual, but I really don’t have the stomach for discussing the spiritual fall of one of the American Titans.

The women who consulted with Cornelius were prostitute daughters of a scam artist father, promoters of free love, early feminism, women’s suffrage, and were sponsors of Marxism in America. By some accounts, one of Vanderbilt’s associations was with a girlfriend of Diamond Jim Fisk, Vanderbilt’s opponent in the Erie Railroad War.

Say what???

So be it. Small world.

Theological Contemplations

Luke 16:13

13“No one can serve two masters. Either you will hate the one and love the other, or you will be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve both God and money.”

I have always found it intriguing that this passage, so clear in Jesus’ condemnation of putting our trust in money, follows so closely the Parable of the Shrewd Manager.

In that earlier passage (Luke 16:1-9) the Lord summarizes what I have seen as a perplexing story with the command to use money to ensure your welcome into heaven.

Use money to get to heaven…

Again: Say what???

The shrewd manager fellow is accused of embezzlement and will be fired by his boss. Knowing he cannot justify his actions (for the accusations are true), he approaches his master’s debtors and, in his capacity as money manager, forgives a portion of each of their debts.

This makes the debtors happy, and presumably the manager will be able to find employment with one of them as soon as loses his job.

That all seems a little on the far side of shady.

As usual, Jesus is thinking at a different level.

He does not condemn the manager (although the guy would seem to richly deserve it, for giving away money that was not his) but instead, Jesus commends him.

The manager used assets under his control to gain acceptance from those who could be important to him.

That is as close as I can come to understanding the point of this passage.

Put like that, it suggests something profound about how I ought to use that with which I have been entrusted to honor the One Who holds my future.

And that thought leads me right to verse 13, above: [You cannot] serve two masters. Either you will hate the one and love the other, or you will be devoted to the one and despise the other.

It is clenched with: You cannot serve both God and money.

If I serve the money, the money requires that I hold it tightly. If I use it to serve God, the money must be released.

You cannot serve both God and money.

The Commodore had an unusually strong relationship with money. He had a gift for acquiring it, and he obviously saw it as a resource to accomplish what he wanted. He dispersed it freely, but not irresponsibly. He understood what it could do for him.

If that was his approach, then he was not far from the kingdom of God. But I fear that having developed the love affair with the money, he failed to make the leap:

Use that with which I have been entrusted to honor the One Who holds my future.

Money is unique. It takes on a compelling life of its own. As Hal Holbrook’s character said (Wall Street, 1987): “The main thing about money, Bud, is that it makes you do things you don't want to do.”

And that is the story of The Commodore, Cornelius Vanderbilt, an American Titan.

Thanks to those of you who have upgraded to a paid subscription. At $50 a year, and further discounted right now through the end of this year, it is a modest commitment, and it helps ensure continued missives like this one. Use the subscribe button to join for free if you’re new, or upgrade to pitch in and help. There is free merch with your annual paid subscription. Thanks much for following! I am honored to have you in the audience!

Curt

Share this post