October 25, 2023

Flip a switch, the lights come on. We have George Westinghouse to thank.

All you who deal with a wayward child, who seems more interested in hobbies, toys and play than schoolwork, take heart! This was young George Westinghouse, 1846 - 1914.

When his father broke a wooden paddle across his backside, the boy pointed to a leather strap hanging on the wall. “Use that one, Father; it’s better,” he offered.

Westinghouse, unlike most of the other titans of America’s Gilded Age, avoided the spotlight. His entire energy was focused on inventing ways to do things more efficiently, safely and cheaper.

After a brief stint with the Union Army during the Civil War, he moved to the budding U.S. Navy in a position maintaining engines on ships.

Then, after an inconclusive and uninteresting semester at college, he dropped out to chase his own steam engine invention. It was a failure.

Derailment and a new career

George’s big break came when he observed workers lift derailed train cars back onto tracks. He invented a rudimentary system for mechanizing this work — the “car replacer” — and, using the lessons learned, turned his attention to an improved braking system for trains.

Because of the difficulty bringing a long train to a stop, generally only 10 cars could be attached to a locomotive. A brakeman served every other car, riding on top. When signaled by a whistle from the conductor, the brakemen would jump down between the cars and turn first one brake wheel on the leading car, and then a second on the following car.

A slip and fall meant losing a limb, or a life. Such accidents were common, and did not do much to stop the train.

Manual braking one car at a time meant that connected cars collided through the coupling with the one in front, making the passenger experience unpredictable and jarring.

Westinghouse fretted over this problem for months, and finally came up with a system of compressed air to activate brakes on each car. Because steam compressed at the locomotive dissipated by the time it traveled the pipe to the last car, a compressed air reservoir was needed at each car.

Westinghouse developed this system and pitched the solution to various railroads without success. No one wanted to incur the expense of retrofitting their cars, especially since there was no guarantee other roads would adopt a compatible system.

Finally, it was bought by the Pennsylvania Railroad, the dominant carrier in America, in 1869. In time, the law required its use by every rail car in the U.S.

With this new system, trains could connect more cars, driving freight costs down. Passengers enjoyed a less jarring ride. Accidental collisions plummeted.

Love, with practical side

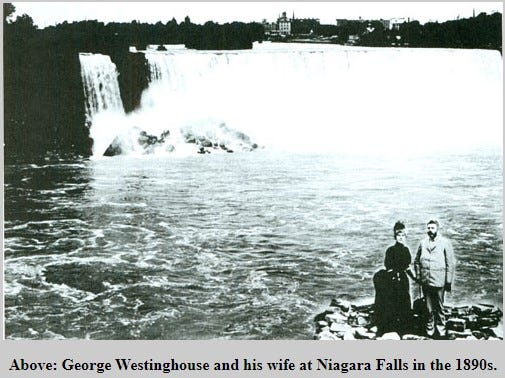

On a train in 1867, Westinghouse met young and beautiful Marguerite Erskine Walker. There were soon married, and she was the love of his life. After 1870, the couple moved to an estate in Pittsburgh, PA, and named it Solitude. Marguerite hoped it would be a place where George could escape his work.

That was the plan, but then natural gas was discovered 20 miles away and caught George’s attention.

Asking Marguerite’s permission, Westinghouse drilled a well in the flower garden at Solitude and found natural gas, which, after only three days of drilling, blew the cap off the well. Set alight by a spark, a roaring fire burned for days, destroying the quiet of the upscale neighborhood, until it could be brought under control. The local fire department dumped water over the house to prevent it catching fire.

An understanding woman, Marguerite was unperturbed. Her only comment was: “…The house still has a roof on it and the kitchen isn’t wrecked.” All was good.

Coal was dirty to mine, dirty to handle, dirty to burn and expensive to deliver. George launched into methods to compress and transport gas. A system of high pressure lines was designed, but the metallurgy of the day was not up to making fittings that would not leak, an insurmountable problem.

Instead of solving the problem, Westinghouse went around it. He placed the leaky high pressure lines inside larger, low pressure lines. When leaks occurred, the gas simply bled off into the outer line and both continued to the destination.

When Westinghouse was unable to obtain right-of-way to bury lines to homes and businesses, he found a bankrupt Pennsylvania business which already had such right-of-way privileges in place. He bought the business, used their routes, and became the leading natural gas provider in Pittsburgh.

The Philosophy of Motion

Moving large volumes across long distances was a problem Westinghouse had first confronted in moving steam from locomotive to caboose. Later, he moved natural gas from well to distribution facility, and then on to city streets, homes and businesses.

To him, it was not so much a technology as a philosophy. For what was arguably the most productive and impactful season of his life, he applied the same principle to electricity.

AC/DC

Direct current, DC, was championed by Thomas Edison. Edison was a household name for such novelties as the phonograph (1878) and incandescent lightbulb (1879).

A brief explanation

Direct current makes electricity flow in one direction only, like a river, from a positive charge to a negative charge. Voltage is always constant. This might seem a no-brainer, but it means that over long distances (more than a mile) the wires carrying the current must be very large in diameter. Also, components are highly susceptible to corrosion. DC power can be stored; a battery (your car, your flashlight) operates on DC.

Alternating current does what it says: The voltage changes rapidly (60 times each second, for example) from positive to negative and back again. AC is easier to transform into higher voltages without increasing wire diameter. Even after adding transformers to step-up or step-down the voltage, the infrastructure buildout for AC is less expensive than DC.

(I was actually a Speech major, so if you have contributions or corrections to offer, feel free to pontificate in the comments below.)

Edison was a champion of direct current electricity. DC was simple to install and easy to handle. However, DC could be moved only short distances, about one mile. This meant that DC power generation plants must dot the landscape. Especially as cities grew, that would become an issue.

As in the conversion from coal to gas, with accompanying cost savings, Westinghouse sought for a way to electrify cities without the burden of thousands of power generating stations.

Westinghouse reached out to Nikola Tesla, who was working on alternating current. Pioneered in Europe, this system used transformers to “step up” voltage for transmission over greater distances, then “step down” at the far end.

Using transformers, AC electricity could be produced at a single location and be transmitted great distances for use by customers. This meant fewer generating stations.

A series of accidental electrocutions in 1901 by direct current, when workers attempted repairs to overhead copper lines, led to public distrust of DC and gave impetus to the AC solution.

As a side note to the “electricity wars,” Edison planned to demonstrate how much more dangerous AC was.

“Old Sparky”

Incredible by today’s standards, Edison used alternating current to electrocute Topsy the elephant on camera. (Don’t click that link.)

The 1903 film is barbaric and disturbing.

Edison also produced a film re-enacting the execution of Leon Czolgosz, who in 1901 had assassinated President William McKinley. In Edison’s version, he attempts to show the inhumanity of the electric chair using alternating current.

The audience is left with the impression that DC is more humane. This was not exactly true; neither one was pretty. The films demonstrated more the graphic effects of the electric chair than the differences between AC and DC.

Despite Edison’s public attacks, Westinghouse and Tesla continued in the development of AC.

Because of the limited number of generating plants that AC required, the economics offered AC electrical power at a lower cost. It won the competition for investment. Two very public developments accelerated adoption of alternating current.

The 1893 World’s Fair, Chicago

To commemorate the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ voyage to the New World, the Columbian Exposition was held in Chicago. In deference to the U.S. presidential election year, it was held not in 1892, but in 1893.

Westinghouse and Edison competed for rights to illuminate the fair. With a lower bid, Westinghouse won the contract with his alternating current system powering 100,000 light bulbs.

The Exposition cost $17 million (1893 dollars) and showed off the first Ferris wheel. The wheel held 36 cars, each the size of railroad cars, for 60 occupants each.

During the three months the fair was open, it was visited by 27 million sight-seers. The U.S. population at the time was 65 million, less than one-tenth of whom had electricity at home.

The 1893 World’s Fair was a game-changer in the demand for electrification.

Niagara Falls Hydroelectric Power

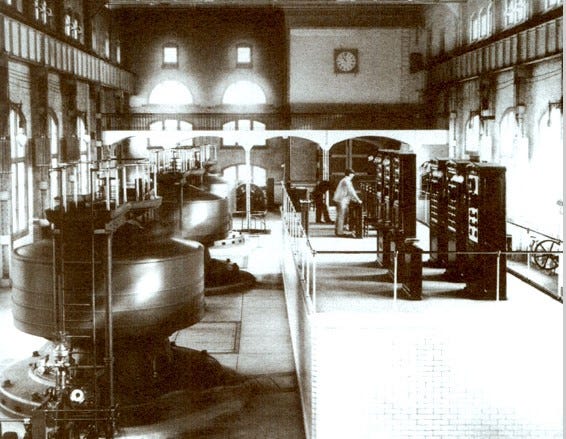

In 1895, Westinghouse and Tesla completed construction of the first hydroelectric power plant at Niagara Falls.

Water wheels had been in use on the Canadian side for years, used for direct operation of machinery. Tesla’s generator was the first use of water power to create electricity.

Using transformers to step up and then step down the power across long transmission lines, electricity was moved 22 miles to Buffalo, New York. This was the first application of electricity moving over long distances.

The Panic of 1907 and Tesla’s demise

George Westinghouse remained in control of his Westinghouse Electric Corporation, established in 1886, until the financial Panic of 1907. Banks failed across the country, and the company, over-extended, went out of business.

Westinghouse had spent heavily to purchase patents and compensate business partners, often accepting their stock as collateral for loans. When the economy contracted and their stock values plummeted, he could not weather the storm.

To help his friend and partner Westinghouse during this time, Nikola Tesla agreed to forego millions of dollars in royalty payments. At the request of Westinghouse, Tesla tore up the contracts and walked away, claiming, “I’m not interested in the money; I’m interested in mankind.”

Tesla continued to publish articles and dabble in innovations, but became increasingly eccentric, eventually receding from public view.

Westinghouse died in 1914 with an estate valued at $50 million; Tesla in 1943, destitute.

Theological Contemplations

Proverbs 20:12-13 The hearing ear and the seeing eye, The LORD has made both of them. Do not love sleep, or you will become poor; Open your eyes, and you will be satisfied with food.

It is true that most of these American Titans of industry saw and heard reality that most of us would have ignored.

How does one “see” the possibility of using compressed air — by definition, something that cannot be seen — to activate railcar brakes simultaneously, sufficient to stop a freight train?

It may be an easy leap to move from steam locomotive compressed air to compressed natural gas. However, leveraging the same concept to the high voltage transmission of electricity is something outside the grasp of most of us.

While he did not create the transformer, once he understood it, he immediately latched onto the concept and saw how it would apply in the widespread distribution of alternating current.

We are left with a few notable takeaways from George Westinghouse:

He had an unusual capability for seeing what could not be seen, and he used this gift to solve problems and make life better.

He had an unusual proclivity for building ethically on others’ accomplishments. He bought patents, he accessed Tesla’s research, he purchased a defunct gas transmission business. All this was done legally and cooperatively, giving credit to whom it was due.

He had an unusual orientation toward making life for the entire population better. Many of Edison’s inventions, while not to be discounted, were for individual enjoyment: The phonograph, the photograph, the motion picture, the light bulb. Westinghouse brought his inventions to the masses: The air brake, natural gas distribution, electricity for a nation.

To borrow and modify a cynical comment on modern America: “A world without the American Titans is a world where people sit in caves, cold, hungry, naked and afraid, wishing someone would invent electricity.”

And a warning: Westinghouse relied on a booming economy to over-extend his financial obligations. Every decade post-Civil War saw a financial panic in the U.S.: 1873, 1882, 1893. Why should the Panic of 1907 be unexpected?

This, too, is a matter of perceiving what cannot be seen.

When the Apostle Paul says, “Do not merely look out for your own interests, but also for the interests of others,” (Philippians 2:4) he indicates that looking out for one’s own interests is not to be condemned. We are to serve others, and we are also to act responsibly in our own interests.

No one ever said that balancing an effective and productive life would be easy.

(Nikola Tesla might be an object lesson in this vein.)

So: The application is to use the senses and the capabilities with which God has gifted us (the seeing eye and the hearing ear) to seek the welfare of others in our sphere of influence. Most of us will not be George Westinghouse, but we can use God’s gifts to honor Him and serve others.

Share this post