November 1, 2023

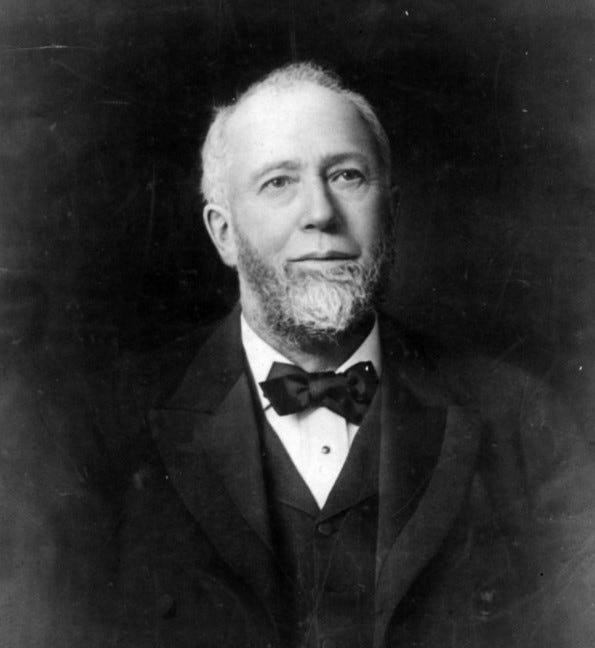

Born into a Cape Cod family of 12 in 1839, a direct descendant of Elder William Brewster from the Mayflower, Gustavus Swift started life on a rock-strewn farm unsuitable for crops, and ended with a multi-million dollar empire of refrigerated rail cars suitable for dressed meat.

Trying to eke out a living by farming land that could not be farmed, Gustavus’ father turned to animal husbandry. The corn would grow, but only in between the rocks in the sandy soil, and could not be harvested effectively.

Grass, however, grew just fine, and offered forage for sheep and cattle.

At 14, Gustavus — christened “Stave” by the family, probably because it was easier to say — bought a heifer from a neighbor for $19, slaughtered it, and taught himself to butcher it in a shed on the farm. Carting the cuts door-to-door, he sold the dressed meat to neighbors for $10 clear profit.

We would all do well with a 52% return.

Stave worked for his older brother Noble to learn the slaughterhouse business.

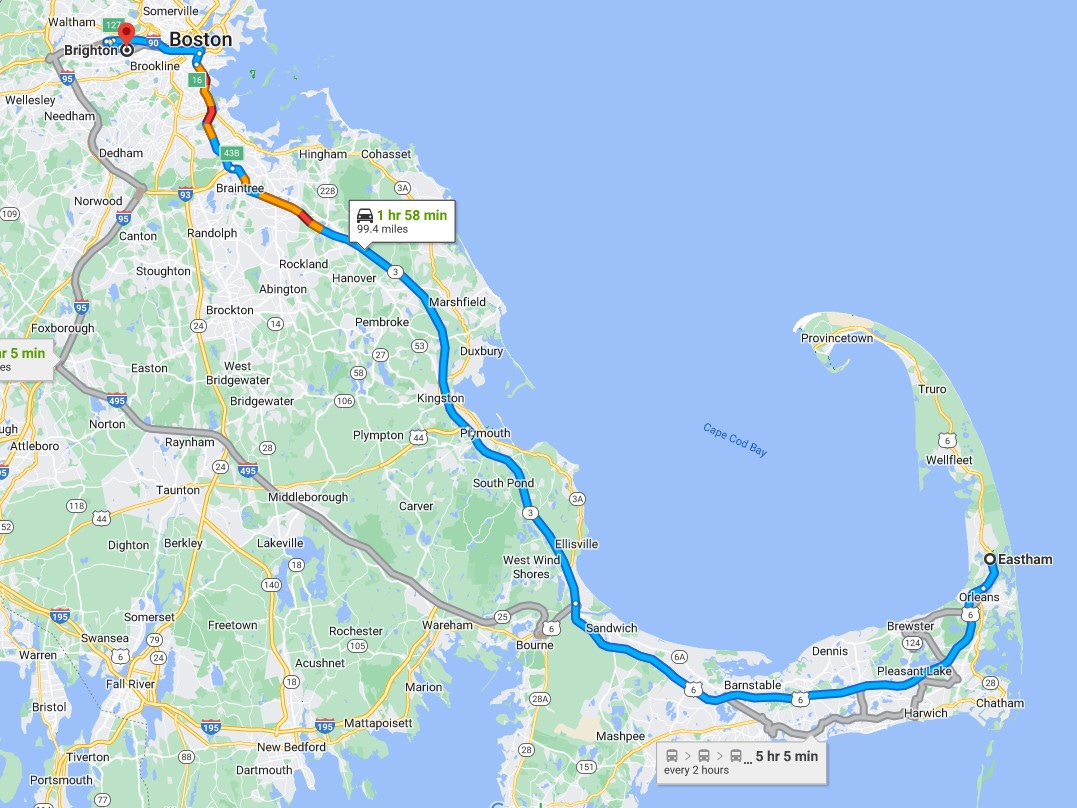

Leaving school after 8th grade, at age 16, Gustavus borrowed $400 from an uncle and bought a small herd of cattle in Boston. By himself, Swift drove them 100 miles to market on Cape Cod. The trip took 10 days and turned a profit.

In 1861, he married Ann Marie Higgins, and the next year opened a small beef and pork butcher shop. Ann Marie kept the books for him and would eventually give him 11 children.

In 1872, Stave partnered with meat processor James Hathaway to open a slaughterhouse in Buffalo, New York. Three years later, the pair moved their business and families to Chicago, the booming center of the livestock market, and there Swift remained.

Beef on the Hoof

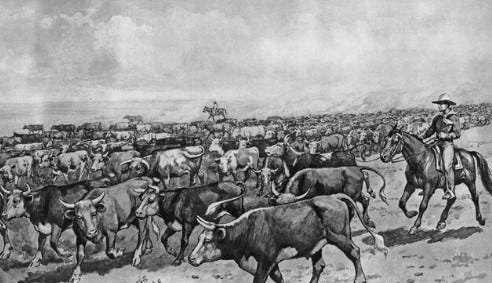

The dynamics of the beef industry was all about transporting the meat to market. The heyday of the cattle drive era was 1876, when western herds were driven sometimes 1200 miles to a railhead, such as Abilene, Kansas, or Kansas City.

Cattle drives were tough on the critters. Herds always lost inventory on the trail, due to malnutrition, lack of water, disease, natural disaster or rustling. Weight loss was also a major drawback. While a colorful season of U.S. history, the cattle drive was inefficient and could be inhumane by today’s standards.

At the end of the drive was an equally unpleasant, arduous and expensive trip in a rail car. It is probably a good thing we cannot understand the panic of the cow.

Until the late 19th century, the animal had to be kept alive, healthy and well-fed until very close to its final destination, where it could be slaughtered. In an era before refrigeration, the cuts of beef, pork and lamb had to be offered fresh.

Swift, with many others of his time, considered that shipping dressed meat would be much more efficient and cheaper than shipping live animals.

Ice Inventions

Several abortive attempts were made to pack beef in ice for transport in rail cars. Problems abounded:

Meat touching the ice would discolor and develop an unpleasant taste.

Meat hung from hooks in a rail car over ice would sway on corners. The sudden shifting weight at a high center of gravity caused derailments.

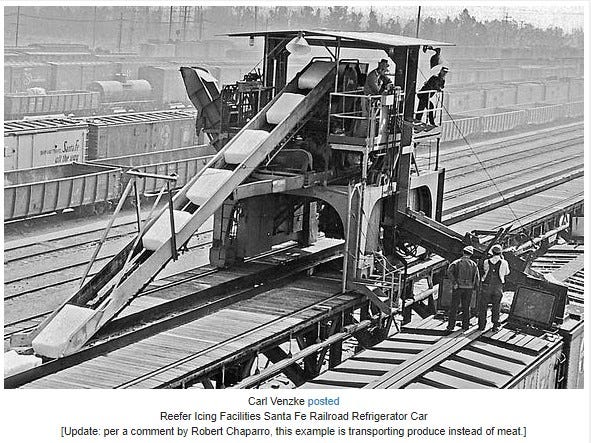

Swift engaged an engineer to design a car with ice stored at the top of the car and the meat packed below. The chilled air would flow downward, and the center of gravity remained low to the floor.

This single concept revolutionized the transport of dressed meat and made shipments vastly cheaper and safer.

The railroads hated it.

Railroads had enormous investment not only in conventional livestock cars, but also in stockyard management, notably at Chicago. Converting from beef on the hoof to refrigerated, dressed cuts completely upset their business model.

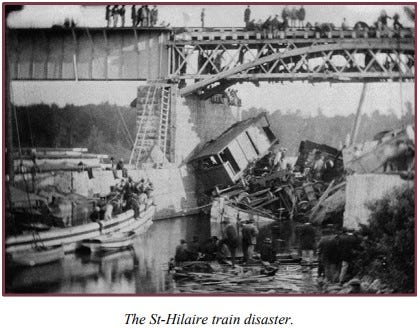

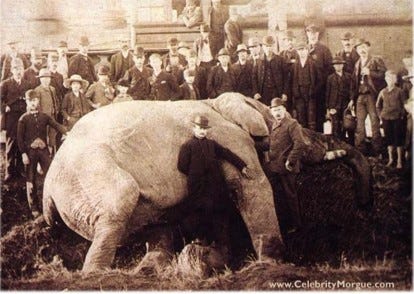

Swift found a railroad that had no investment in the Chicago stockyards: The Grand Trunk Railway (GTR) serving markets across Canada. Despite it’s propensity for horrendous accidents (99 passengers killed in a spectacular 1864 plunge from a trestle in Quebec; the unfortunate death of Jumbo, the famous circus elephant who inadvisably charged a locomotive in Ontario, 1885), Swift contracted with GTR.

Gustavus Swift used his specially designed refrigerated cars to ship dressed beef from Chicago through Michigan and onto Montreal. With GTR freight, distribution spread across Canada.

U.S. meat processors took note of the Canadian experiment, and the idea took hold despite railroad resistance.

In a four-year period in the 1880s, dressed beef deliveries to New York grew from 2,600 tons to 70,000 tons a year. Live cattle shipments declined by one-third during that time.

By 1886, “Big Meat” launched an anti-Swift public relations campaign. Swift responded by developing rail shipment contracts to smaller markets. He established delivery routes by special refrigerated rail car to hundreds of small towns, and simply went around the big eastern markets.

Swift spent massively on advertising. His products developed a reputation for consistency, quality, availability and low cost.

At the same time, he leveraged the refrigeration techniques — still using ice, mostly harvested from the Great Lakes area — to establish intercontinental shipping. He began to serve markets not only in Great Britain, but also in the far east: From Honolulu to Shanghai.

While most meat packers suffered criticism from those who objected to the waste byproducts from processing, Swift was a believer in profiting from those byproducts. He pioneered processes to produce soap, glue, fertilizer, hairbrushes, knife handles, and pharmaceuticals from the carcasses.

Swift was innovative with production techniques. Henry Ford got the idea for a moving assembly line by reviewing Swift’s “disassembly line” (as it were) for slaughtered carcasses.

Swift is credited with the claim that, when processing a pork carcass, he would use “everything but the squeal.”

Gustavus Swift died in 1903 at age 64, of complications from gall bladder surgery. Lying in bed at home, recovering from the operation, Ann was reading poetry to him when he suddenly raised himself, looked out a window, and collapsed in death.

The business that bore his name was valued at that time at $135 million.

A Life Well-Lived

By all accounts, Gustavus Swift and his wife were deeply in love. Ann Marie stayed by his side through the early years of his interest in meat packing, an intrinsically repulsive business to a genteel housewife. Of the 11 children, 9 survived to adulthood.

Gustavus was directly descended from the Mayflower and could easily have built on his family history to become the envy of the Chicago elite. But he and his wife shunned the high life, choosing to live in a working class neighborhood in more modest surroundings.

Swift rode a horse to work, and came home for lunch every day. Dinnertimes in the evening were consistently at home, all the family gathered around the table.

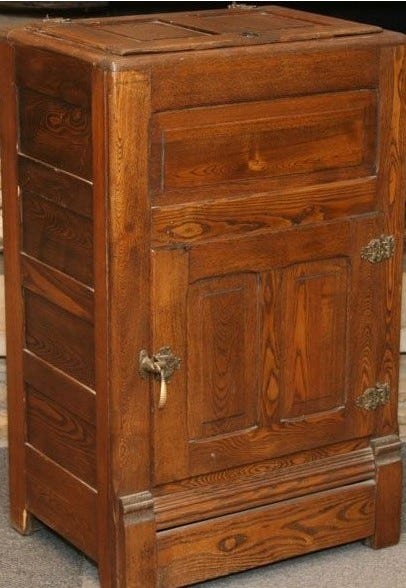

In a biography, daughter Helen wrote of Gustavus’ playful demeanor toward Ann Marie. Mom was petite and lightweight. Dad would pick her up bodily and set her atop the 5-foot tall ice box in the kitchen.

“Gustavus! Don’t be silly. Take me down!”

[Smiling] “You know, Ann, I like the looks of you up there.'“

“Gustavus, if you don’t let me down, I’ll kick you!”

The parents ensured the children understood money management. On birthdays, Swift would present each child with two shares of company stock, one a gift, the other to be purchased from the son’s or daughter’s dividends.

In terms of financial training, the next generation understood that a going concern was constantly investing in the future and leveraging a modest amount of debt.

Theological Contemplations

The Bible speaks from the earliest chapters about the slaughter business:

Genesis 27:9 Go now to the flock and bring me two choice young goats from there, so that I may prepare them as a delicious meal for your father…

Deuteronomy 12:21 …You may slaughter animals from the herds and flocks the Lord has given you, as I have commanded you, and… you may eat as much of them as you want.

Romans 14:1-2 Accept the one whose faith is weak, without quarreling over disputable matters. One person’s faith allows them to eat anything, but another, whose faith is weak, eats only vegetables.

But that is hardly the point of the lessons we derive from the life and times of Gustavus F. Swift. More relevant, I think, is this passage describing the skilled labor who created the holy decorations of the Tabernacle, used after the exodus from Egypt:

Exodus 35:35 He has filled them with skill to do all kinds of work…

Work is commended in the Bible from start to finish. Work implies study, persistence, practice, diligence, and in many cases creativity to ask the hard question: Isn’t there a better way to do this?

“Better” means cheaper and faster with higher quality.

“Better” is always associated with improving the life of the recipient.

“Better” usually results in financial benefits for the one who arrives at the answer.

Gustavus Swift not only developed skill in animal husbandry, slaughter, butchery and packaging, but he also found ways to sell and distribute the products. His approach to process-and-ship rather than ship-and-process was revolutionary, requiring new technology in refrigeration, innovations in railcars, construction of remote cold storage, and industrial-level developments in ice harvesting.

Swift brought fresh cuts of meat, at reasonable prices, within the reach of millions of households.

None of which would have been possible without using his resources, his ingenuity and his boldness to aggressively promote his work to people who needed his product.

By the time Swift reached the end of his life, he had created an entire industry and improved the standard of living for millions. By the dawn of the 20th century, his direct processing plants by themselves employed over 20,000 people, apart from the considerable army of workers in subsidiary businesses.

All this, and he had family life anyone would envy.

What’s not to like?

And that is the story of Gustavus Swift, an American Titan, and that’s what the Alligator has considered on this first day of November, 2023.

Please share the episode! Someone else might really like to hear it!

Curt

Share this post