November 15, 2023

[Note: If you are reading this as text, thank you, but you will miss some of the musical highlights on the audio version.]

American Titans

This is an installment of the American Titans series on The Alligator Blog, a brief look at the accomplishments and the personal lives of a dozen men who shaped modern America.

The Gilded Age, from just after the Civil War to the turn of the century, roughly 1877 to 1901, is when most of the cool things happened: Big rail, big steel, big oil, big electricity, unbridled stock market, political corruption, gold rushes, the Wild West.

Character always counts, and the takeaways we draw from the character of these characters are as relevant in the 21st century as they were in the 19th.

I hope you enjoy today’s episode on Thomas Alva Edison.

Thomas Alva Edison

For a man who nicknamed his daughter and son Dot and Dash, it may be no surprise that Thomas Alva Edison, 1847-1931, got his start as a telegraph operator.

The story of Edison’s creative genius is as broad in its effect as it is tedious to document. Read the extensive Wikipedia entry for yourself… it took me most of an afternoon.

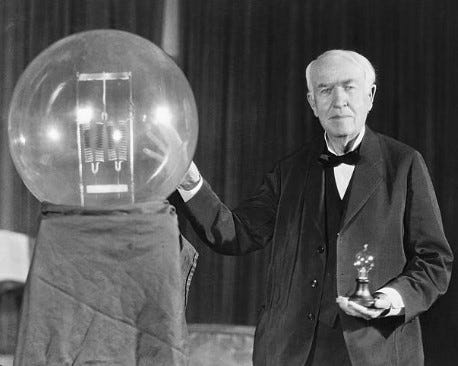

Principally today we credit Edison for the creation of the light bulb and the incandescent filament inside it. Neither are precisely true; various versions of filament had been around for well over a hundred years before the Wizard of Menlo Park came on the scene.

Through what most of us would consider hyper-focused obsession, Edison experimented with materials until he found a combination that would make electric light brighter and last longer at lower cost.

Newspaper boy

Young Edison got his start selling newspapers and candy on the regular train route from Port Huron (Michigan) to Detroit. When the Battle of Shiloh, an early large-scale engagement of the Civil War, unexpectedly claimed 20,000 lives in 1862, he recognized the immediate breaking news. The 15-year-old purchased 1,000 copies and sold them all at marked-up prices to rail passengers.

With an eye for attention to detail and the luck to be in the right place at the right time, he one day pulled a railroad telegrapher’s young son from in front of a runaway train. In gratitude, the telegrapher taught Edison Morse Code and employed him in the office.

In 1869, Edison quit the telegraph job, having learned the basics of electrical transmission, and turned his attention to his own inventions. In a few months, he patented a fast and efficient way for legislators to cast their votes using an electric vote recorder.

What he had failed to consider was that the legislators had no interest in either speed or efficiency; they customarily used the time-consuming roll call process to lobby their counterparts.

It was this experience, plus probably also the recognition that normal consumers without political objectives would pay good money for things done fast and cheap, that turned his interest to mass-market inventions.

First came the business that he knew well.

Telegraphy

In 1872, Western Union engaged Edison to make telegraph transmission more efficient by sending simultaneous messages on a single set of wires. Building on work by other inventors, Edison developed a method for sending two messages over the same wire at the same time, assigning each channel a unique signal strength.

Simultaneous transmission had already been perfected, making the messages duplex (two-way) rather than simplex (one-way), which had doubled the line capacity. Edison’s development allowed quadruplex (4-way) messaging, doubling it again.

This multiplex method, continually refined and upgraded, was used for decades.

Talking machines

In 1877, Edison set his sights on voice recordings.

Originally conceived as a way for businessmen to record letters for later typing and mailing, Edison discovered that there was a huge consumer interest in listening to almost anything recorded: Vaudeville routines, people whistling, others merely laughing, dolls speaking.

Coin-slot machines sprung up on sidewalks where pedestrians could listen to jokes, monologs and songs. A Missouri machine netted $100 in one week.

Microphones

In 1876, with everything else going on, he turned his attention to improving the transmitter used in Bell’s new telephone contraption. Bell had used a pair of electrically charged metallic membranes vibrating with the force of speech.

Edison improved this by separating the metal plates with carbon granules and allowing the electrical current to fluctuate. It produced transmitted speech that was clear, effective, cheap and durable. The design was used until the 1970s.

And by the way, the product was improved as he began to roast the carbon particles first.

Music…

In 1903 The Victor Talking Machine Company recorded Italian tenor Enrico Caruso singing opera, of all things, and everyone wanted a copy. A 1920 version of “Crazy Blues” by Mamie Smith sold a million scratchy copies on a disk, and jazz became an overnight sensation.

[Music interlude]

Interestingly, Edison’s phonograph not only made music available to the masses, the technology actually changed the music itself. Disks were only good for about three minutes of audio.

Igor Stravinsky composed his 1925 piano suite “Serenade in A” in several short movements, so that each could be recorded on a disk.

[Music interlude]

…and lights

The patents came fast and furious. Edison’s first public demonstration of his carbon-filament bulb was at his laboratory at Menlo Park, New Jersey on New Year’s Eve, 1879.

By the time Edison was done inventing, he had recorded 1,093 patents. This record has since been broken, but in the Gilded Age it was a shocking number.

Menlo Park

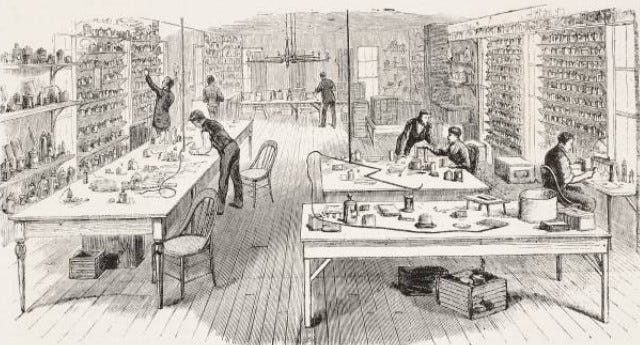

He developed his laboratory at Menlo Park into a rambling set of buildings where not just invention, but experimentation could take place. From an early age, Edison seems to have intuited that massive repetitions of trial-and-error would be required to find the right materials. He required physical properties for his inventions that offered superior performance at low cost.

He stocked Menlo Park with:

“…eight thousand kinds of chemicals, every kind of screw made, every size of needle, every kind of cord or wire, hair of humans, horses, hogs, cows, rabbits, goats, minx, camels ... silk in every texture, cocoons, various kinds of hoofs, shark's teeth, deer horns, tortoise shell ... cork, resin, varnish and oil, ostrich feathers, a peacock's tail, jet, amber, rubber, all ores…”

The 8,000 number comes up again in Edison literature, making us suspect it is a generic rather than a descriptive term.

Early in Edison’s inventing career, about 1867, he experimented with ways to improve conventional lead-acid batteries. Working late one night at his second-floor Western Union laboratory, he spilled liquid sulfuric acid. It seeped through cracks in the floorboards, dripped onto the desk in the owner’s office, and the next morning Edison was fired.

Edison shifted his attention to other chemicals less likely to burn up the boss’ books. After thousands of failed experiments with the batteries, he was heard to say, "Well, at least we know 8,000 things that don't work."

Eventually, this work paved the way for the development of the dry cell alkaline battery, probably the most widely used and commercially profitable invention he ever made.

Too much data

There is much more to tell, but you get the idea. A few of the thousand items he invented are here:

Electrographic vote-recorder

Pneumatic stencil pen (tattoo pen)

Magnetic ore-separator

Electric power meter

Method of preserving fruit

Alkaline battery for electric cars

Concrete house

Concrete furniture

Phonograph for dolls

… and the Spirit Phone, for — yes — talking with the dead.

More on that below.

Edison famously championed direct current for distribution to homes and businesses. He dramatically lost that competition to the George Westinghouse/Nikola Tesla application of alternating current. In 1893 the Chicago World’s Fair chose AC over DC for lighting, and Thomas Edison receded from the electric distribution business. (Even though, for some reason, Con-Edison still bears his name today.)

Edison’s inventions were all about mass appeal. Virtually every project to which he applied his considerable genius was done with a view toward faster, cheaper and more reliable.

Those targets are real winners.

His personal life, however, leaves some questions.

Theological Contemplations

Thomas Edison, like others of his time in the Progressive Era, was a free thinker. Skeptical of traditional Christian thought, he considered himself not an atheist, not exactly an agnostic, but perhaps a deist. (Quotes in this section are from www.learnreligions.com.)

I do not believe in the God of the theologians; but that there is a Supreme Intelligence I do not doubt.

Edison was firmly committed to scientific endeavor, which led him to a conviction that only that which could be produced in a laboratory could be understood to be true.

My mind is incapable of conceiving such a thing as a soul. I may be in error, and man may have a soul; but I simply do not believe it.

Which somehow led him to the Spirit Phone.

Edison apparently believed that he — and everyone else — was made of a collection of physical cells. After death, those cells would be scattered, through normal decomposition of the body.

In 1920, at age 73, he commented to The American Magazine that he had been working on “an apparatus to see if it is possible for personalities which have left this earth to communicate with us,” apparently through electrically collecting those dispersed cells.

He went further, telling his friend B. C. Forbes, editor of Forbes Magazine: “If this [communicating with the dead] is ever accomplished it will be accomplished not by any occult, mystifying, mysterious or weird means, such as are employed by so-called mediums, but by scientific methods.”

Edison based this on his belief that a living person is made up of “swarms” of infinitesimally small components. After death, these swarms would take form elsewhere, functioning in some other environment.

He theorized that it should be possible to detect those swarms by electrical means.

It is possible that an experiment was set up in 1920 — in conjunction with what we could only call a seance — using an “electric ghost machine” to project a thin beam of light striking a photo-electric cell. The light acting on the cell would set up a tiny electrical current. Any interruption of that current might thus detect the presence of some unseen matter in the space between light and cell; A swarm.

I found no validation that such an experiment was ever conducted, but it is consistent with Edison’s earlier comments on the subject, offered on multiple occasions. Edison’s defenders later claimed he had only been joking, merely pulling the leg of his listeners.

It was, after all, an era which saw huge interest in spiritualism. Culturally, some have speculated this shift from a traditional, western, religious view was in response to the shocking deaths of World War I.

Leaving the idea of the Spirit Phone, or Ghost Detector, we are still left with Edison’s own very real and very serious comments about the state of the dead.

From my reading of Edison’s life, the greatest inventor in American history missed the one great truth:

The earth is the LORD'S, and the fulness thereof; the world, and they that dwell therein. Psalm 24:1 (KJV)

In the context of searching for truth, employing creativity, imagination and relentless pursuit — which were Edison’s hallmarks — a second passage comes to mind:

…The kingdom of heaven is like a merchant looking for fine pearls. When he found one of great value, he went away and sold everything he had and bought it. Matthew 13:45 (NIV)

May we have the eyes to see that one pearl of great value, and the courage to take hold of it.

And that is the story of Thomas Alva Edison, an American Titan. There are lessons we draw from him, but like the examination of other mere mortals, we use discernment to sift through his story, take the good, and leave the bad on the table.

If you are new to The Alligator Blog, use the subscribe button below to add your name to our mailing list so that we may spam your inbox regularly with newsletters like this one. If you’re a regular, take the plunge and upgrade to a paid subscription, $50 a year and right now available at a 15% discount.

One way or the other, we are delighted to have you in the Alligator Audience!

Other episodes in the American Titans series are available at www.alligatorpublishing.com in the tab The Alligator Blog. You can also find them at alligatorpublishing.substack.com.

Curt

[more music from Mamie Smith and the Jazz Dogs]

Share this post