December 6, 2023

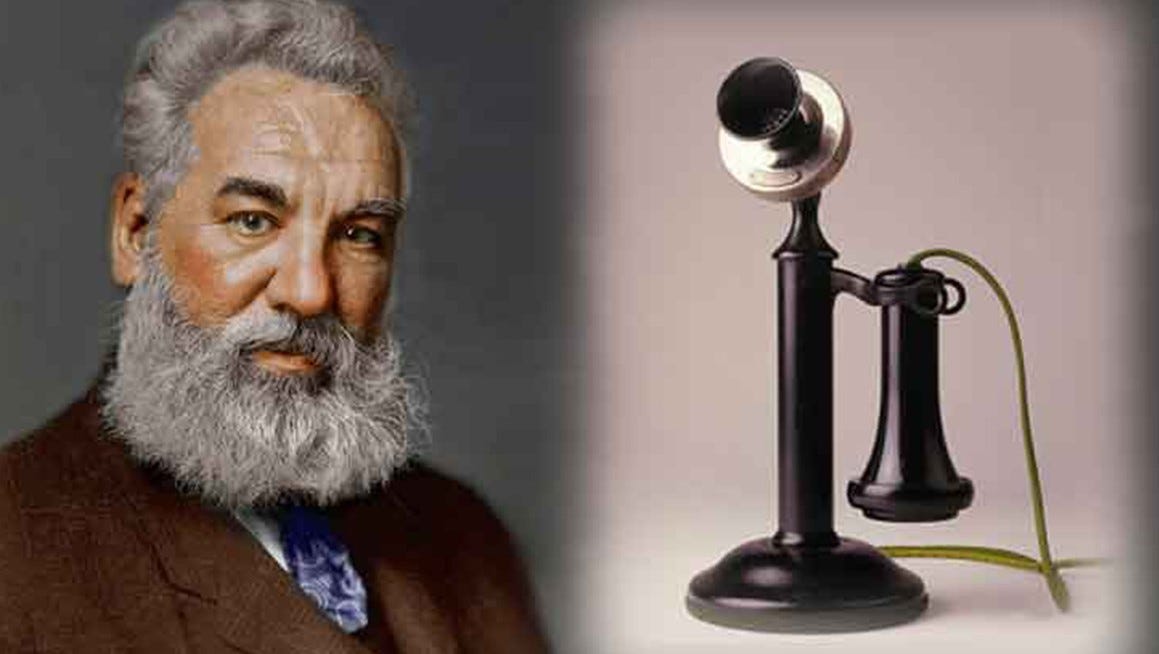

This installment of the American Titans series on The Alligator Blog is of Alexander Graham Bell, 1847 - 1922, who began life learning to speak with his deaf mother and ended his career giving speech to the whole world.

In Scotland, Bell’s mother began to go deaf when the young man was 12. With a bent toward experimentation and problem-solving, Alexander developed a special closeness with his mother. He developed a system for tapping words, and routinely sat close to her, tapping the family conversation on her arm.

With a father and grandfather both involved in elocution and a mother growing deaf, Bell was naturally drawn to the study of voice.

Theorizing that the sounds made by human speech could be broken down into tiny component audible utterances, young Bell experimented with Trouve, the family’s Skye Terrier dog.

After teaching Trouve to produce a continual growl, Alexander reached into the terrier’s mouth and manipulated the tongue and vocal chords. Eventually, he astonished friends and family by teaching Trouve to say, “How are you, grandmama?”

If they used their imagination.

Bell’s father, Alexander Melville Bell, invented Visible Speech in 1867. It was a notation system for speech sounds that could be written, and that guided pronunciation. Also known as the Physiological Alphabet, Visible Speech was used to explain how to produce both vowels and consonants, regardless of the language being spoken.

After losing a brother to tuberculosis, and when his father’s health began to deteriorate, the family moved to Ontario for a more healthy climate. There, young Bell became acquainted with a nearby tribe of Mohawk Indians, learned their language and encoded it in Visible Speech.

He was made an Honorary Chief and danced with them, wearing a ceremonial headdress.

Alexander had written a thesis on the talking dog experiment and submitted it to a doctor who worked in philology. In return, the doctor provided young Bell with a book by a German scientist who experimented with electrically produced tones to synthesize speech.

Young Bell laboriously translated the book himself so that he could study it, and this prompted on-going experimentation once on the American continent.

He produced tones with tuning forks, and hypothesized that if he could produce vowels using electrically generated tones, he could also produce consonants.

An interesting note is that Bell had made errors in the translation of the book. His incorrect understanding of what the German had written led Bell to focus on the electrical reproduction of sound, which was not at all what the book had suggested.

“If I had been able to read German, I might never have commenced my experiments!”

During the time in Canada, Bell and his father taught language skills to the deaf. In 1871, Bell Senior was offered a position in Boston in what would later become the Horace Mann School for the Deaf. After the family moved there, young Bell opened his own school for private tutoring of the deaf. One of his pupils was Helen Keller.

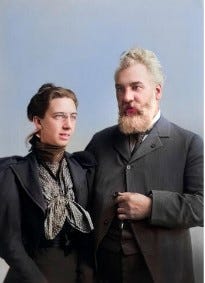

Another was Mabel Hubbard, some 10 years younger than Bell. The girl had been stricken with deafness at age 5 as a result of scarlet fever. As a teen in Boston in 1872, she was sent to Bell for tutoring.

A romance began.

In 1874, Bell merged his study of speech and the electrical production of tones with the new sensation of the telegraph. He mentioned his work to a wealthy investor and found financial support.

He also found Thomas Watson, an electrical engineer, and hired him to assist with his experiments. They were using reeds to produce electrical tones in a field they called acoustic telegraphy. By accident the two discovered that overtones were produced by the reed when the sounds were transmitted by wire.

Overtones gave the promise of generating recognizable speech. The overtones meant that only a single reed was required, rather than many.

Bell was able to effectively transmit distinct tones, and the patent race was on.

At that time, Great Britain would only approve a patent if the invention had not been patented in any other nation. Bell instructed his lawyers to apply first for a patent in England.

When that patent was approved in 1876, he filed with the U.S. Patent Office. That patent was also granted, and the legal wrangling began.

The Patent Office Wars

Another inventor, Elisha Gray, applied for basically the same invention on the same day. There was much confusion at the time, and remains to this day, over who was responsible for the initial patent that would become the telephone.

Over the next 20 years, Bell defended against 587 legal challenges, including 5 trips to the U.S. Supreme Court. He won every case.

Bell’s legal victories were due in large part to the meticulous notes he had made beginning as a pre-teen experimenter in Scotland. There was copious detail in family letters, and these, along with his notes, showed the decades of investment in his invention.

In March, 1876, Bell spoke into a device in his laboratory, summoning Watson. “Watson, come here. I need you.” Watson heard the message in a distant room, and this was the first telephonic communication where intelligible words were heard.

On October 9, 1876, the first successful two-way telephone call was demonstrated from Boston to Cambridge, a distance of 2-1/2 miles.

Monetization

Bell sought to profit from his invention. He offered the patent for sale to Western Union, which dominated the telegraph business, for $100,000 ($2.7 million in 2023 dollars).

Western Union declined because the telephone appeared to be nothing more than a toy. No real work could be accomplished by telephone. The printing telegraph had already been in use for years and provided a paper record of electrical communication. Buy/sell orders, for example, could be proven with the printing telegraph.

Mere voice, with no record, was of no interest to Western Union, a company valued at more than $40 million.

Two years later, in 1878, the president of Western Union proclaimed Bell’s patent would be a bargain at $25 million ($750 million, 2023 dollars), which was 10 times the price when he had earlier turned it down.

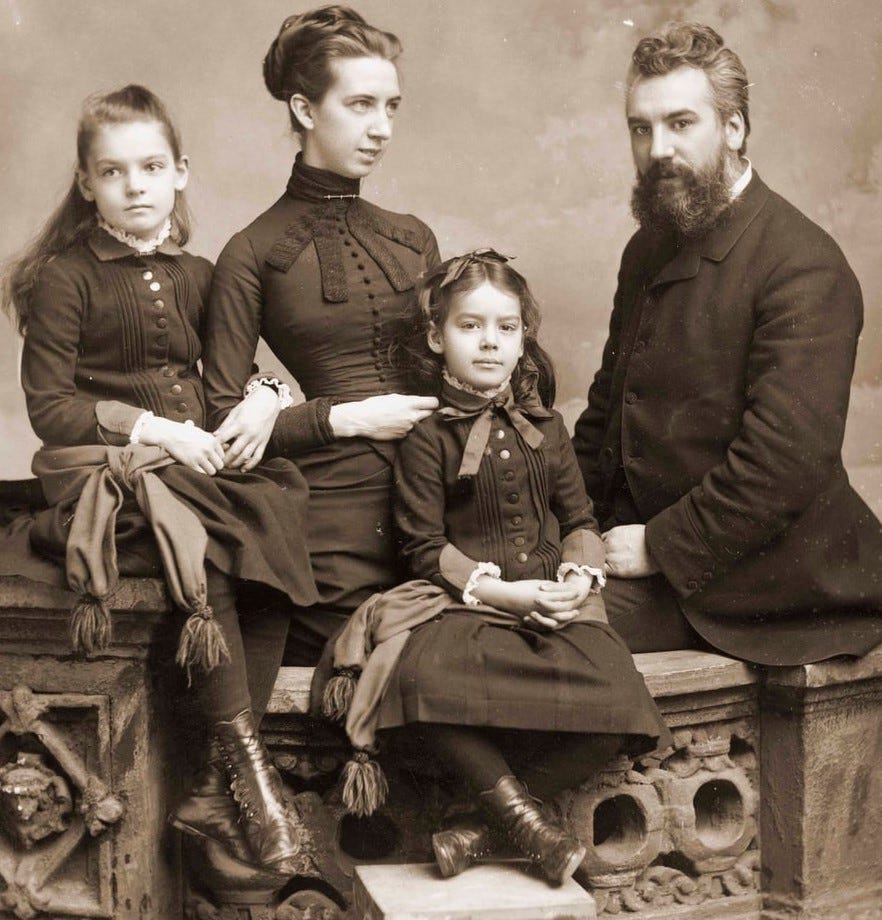

A year after the patent, and the rejection by Western Union, Bell formed the Bell Telephone Company. A few days later, he and Mabel Hubbard were married. His wedding gift to her was 99% of the stock in his new company.

They had four children, of whom two survived to adulthood.

Inventor turned salesman

Bell launched into an aggressive, energetic campaign of demonstrating and improving his new telephone invention. In 1877 he showed it to Queen Victoria. The queen was impressed, but remarked that the voices “were rather faint.”

Once Bell purchased Thomas Edison’s patent for the carbon microphone, the sound quality took a sudden leap forward. The price was $50,000 (1877 dollars) but the value of the patent was incalculable.

In 1879 Alexander and Mabel moved to Washington, D.C., in part to be close to the legal court challenges.

In 1915 he became a naturalized U.S. citizen and proclaimed his love for his adopted country, echoing Teddy Roosevelt: “I am not one of those hyphenated Americans!”

Theodore Vail

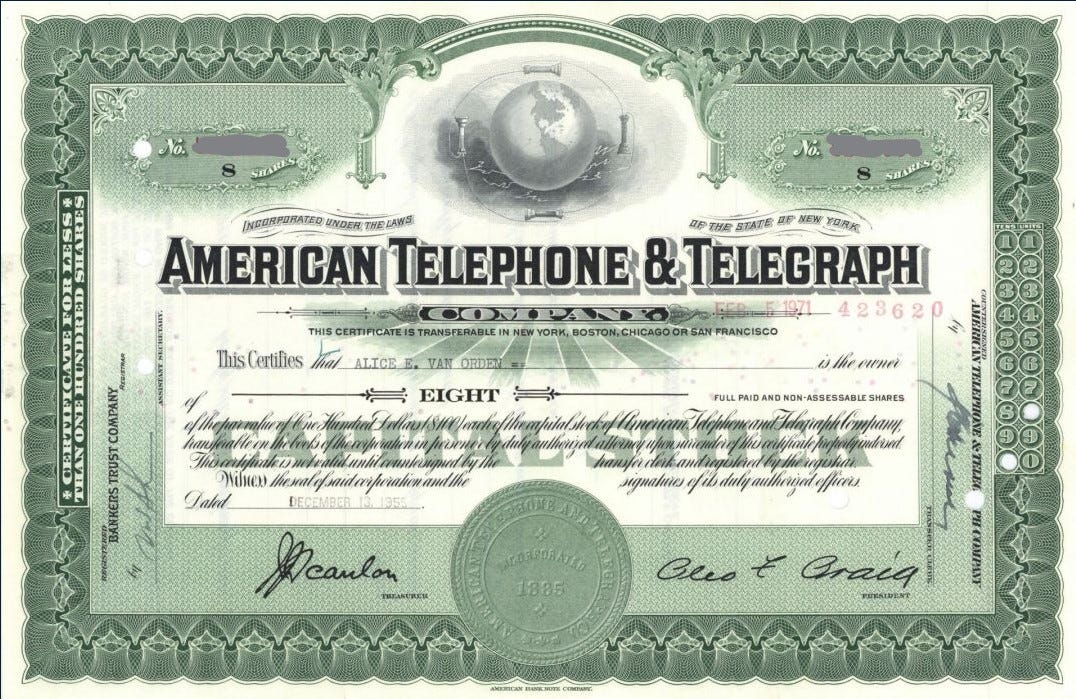

Not so well known is the name of the man who rescued the early Bell Telephone Company from collapse.

In 1878, Theodore Vail joined the fledging new company just after it’s founding. The other early directors, including Bell himself, saw the purpose of the company was to milk the patents for all they were worth.

By contrast, Vail’s emphasis was on providing outstanding customer service to build loyalty among the consumer base. Disagreements with his peers led to his departure from Bell after only two years.

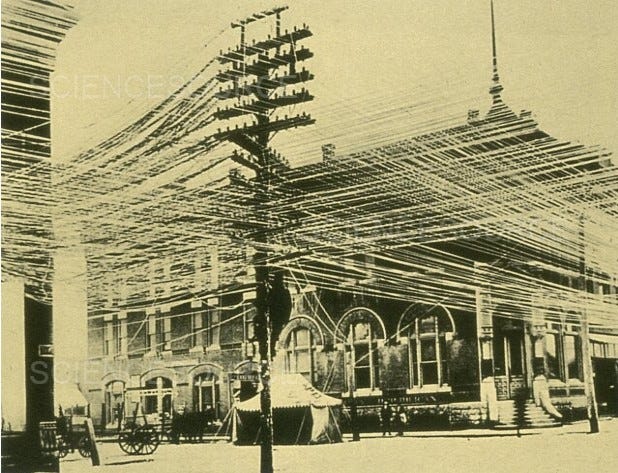

In two decades, the patents expired. Other competitors could now take part in a functioning telephone business, and a commercial war ensued. In many towns, a resident was required to own multiple telephones, and have multiple wires entering his home, in order to communicate with those on other networks.

The Bell company brought Vail back to straighten things out. Instead of opposing independent efforts to dominate the telephone business, he welcomed their interconnection with the Bell network. Practices were established to make service from different providers mutually profitable.

Vail emphasized standardization to facilitate the customer experience using the telephone, recognizing that the consumer was the population that would support continued growth.

Vail made two other indispensable changes. First, he redesigned stock offerings to appeal to smaller investors focused on steady income and growth.

Second, he insisted on a recurring lease approach to the provision of wires and telephones. A Bell telephone could not be purchased for any price; but it could be leased. This ensured a continuing source of revenue to support expanding network improvements.

An observer noted: “Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone, but Theodore Vail invented the telephone business.”

Later inventions

Bell and his wife built a vacation home on an island in Nova Scotia. The house was called Beinn Bhreagh (Gaelic: Beautiful Mountain). Bell spent much time on the water there, satisfying a hobbyist’s attraction to boating.

His inventive work did not stop. He developed a hydroplane for use on the water, and an early version of a flying aeroplane. He experimented with heredity in breeding sheep. He invented a crude metal detector and used it (unsuccessfully) to search for the bullet that eventually killed President Garfield in 1881.

Bell had experimented with using electro-magnets to capture spoken words, but abandoned the project as impractical. Later, his concept saw the creation of the tape recorder.

Bell considered his most significant invention the ability to transmit spoken language by means of a concentrated beam of light. The light struck a flexible mirror, which was sensitive to rapid changes in intensity. When reflected from this mirror to a receiving station, a similarly sensitive surface would vibrate, creating an audible reproduction of the speaker’s voice.

Bell’s “photophone” was never produced, but his early experimentation led to the eventual creation of fiber optic cables.

The End

After a marriage of 45 years and the accumulation of untold wealth, Alexander Graham Bell succumbed to complications from diabetes on August 2, 1922.

At his deathbed, deaf Mabel, who owed him so much and loved him so dearly, whispered, “Don’t leave me.”

Bell silently signed to her one word, “No…” and then died.

At the funeral, Mabel asked that no one wear black. A soloist sang a verse from Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Requiem:”

Under a wide and starry sky,

Dig the grave and let me lie.

Glad did I live and gladly die

And I laid me down with a will.

To mark his death, every telephone in North America was silenced for one minute, at 6:25 PM Eastern Time on the day of his funeral.

Takeaways

What do we learn from the great telephone inventor?

An enquiring mind. Bell was interested in almost everything he touched. From piano to sound waves to the position of the tongue and palate to electrical voltage to light waves to sheep breeding, nothing was outside his sphere of interest.

Determination. He accepted his situation and was determined to find a way to deal with it. He discovered at about age 12 that, while his mother was going deaf, she could hear his words via bone conduction. He spoke to her by placing his lips on her forehead, and she could understand him clearly. Later, he saw Mabel’s deafness as no hindrance to romance. It appeared he could see beyond the physical limitation.

Shrewdness. Recognizing there would be a market for telephone service on both sides of the Atlantic, he filed his patent in Great Britain first. That country would not grant a patent — and thus preclude him from profits there — unless it was initially filed there. This was a great risk, and he very nearly lost the race in the U.S. to Elisha Gray.

Resiliency. 587 lawsuits! Bell withstood them all, including 5 separate trips to the Supreme Court. In order to fight this war successfully, he needed to be close to the action. He left his beloved Boston and moved to D.C. Only his continuous, robust and detailed note-taking kept his legal claims alive. Other inventors had equally worthy ideas, but lacked the documentation to back them up.

Self Promotion. Having invented what he clearly recognized would change the world, Alexander Graham Bell threw himself into the world of sales and marketing. His energy was endless as he traveled from one demonstration to another. A honeymoon to Europe turned into a working vacation as he showed off his new telephone contraption to prospective markets.

Propriety. I can’t resist this one. Bell married Mabel only after his company had been established. They had courted for some time and were obviously headed for a wedding. I suppose unwittingly, Bell had obeyed the Biblical injunction: Prepare your work outside, and make it ready for yourself in the field; Afterward, then, build your house. (Proverbs 24:27)

Theological Contemplations

Bell once remarked to Mabel, “I have always considered myself as an agnostic. But I have now discovered than I am a Unitarian Agnostic.” This came after he found a pamphlet on Unitarianism.

Not much is known of Bell’s faith profile. Never a regular church-goer, he seems to have adopted the elite progressivism of his day: He relied on observable scientifically proven fact, disdaining traditional faith.

His remarkable ability to theorize, visualize and prove invisible concepts with physical components perhaps led him to a bias toward only that which could be measured in a laboratory and documented with numbers. As far as faith is concerned, this is a spiritually dangerous focus. It is akin to driving a car with blinders on.

Along with other notables of his day, Bell also endorsed eugenics. In Bell’s case, he specifically wrote that deaf persons not be allowed to reproduce, believing the genetic link would pass on the disability.

This seems an odd disconnect from the obvious devotion to both his deaf mother and his deaf wife, and is a clear rejection of Scripture.

Consider Psalm 139:16. Your eyes saw my unformed body; all the days ordained for me were written in your book before one of them came to be.

Two passages from Proverbs 25 come to mind when considering Alexander Graham Bell.

Proverbs 25:2 It is the glory of God to conceal a matter; to search out a matter is the glory of kings.

Without doubt, Bell was a “king” of the American Titans. Searching out the matter of turning spoken words into electrical impulses and back into words at the distant end of a thin wire was magic at the time.

Proverbs 25:25 Like cold water to a weary soul is good news from a distant land.

Whether the distant news is good or bad, there is no doubt the delivery of news was an absolute world changer.

And that is the story of Alexander Graham Bell, an American Titan.

Pick up your cell phone and send a text. Just because you can.

Curt

Share this post