When one of the toughest, most battle-hardened and vicious generals in British history threatened to burn and murder his way through colonial America, he believed he was an unstoppable force.

And he was, until he met back country American mountain men. They brought him to a dead stop. An actual dead stop.

Patrick Ferguson, born in Scotland, was a veteran of the Seven Years’ War. Serving the British Crown in the colonies, he was severely wounded — shot in the elbow — at the Battle of Brandywine in Pennsylvania in 1777. After a year convalescing from the amputation of his right arm, he took to the field again.

Having re-trained himself to use pistol and sword with his non-dominant left hand, Ferguson led an early morning attack on Patriot troops at Little Egg Harbor in New Jersey. Fifty Americans were bayoneted in their beds and established Ferguson’s reputation as a brutal warrior not to be challenged. The Little Egg Harbor massacre accelerated Ferguson’s career.

He was promoted to Major in October 1779 and assigned to Lieutenant General Charles, Lord Cornwallis.

The War Moves South

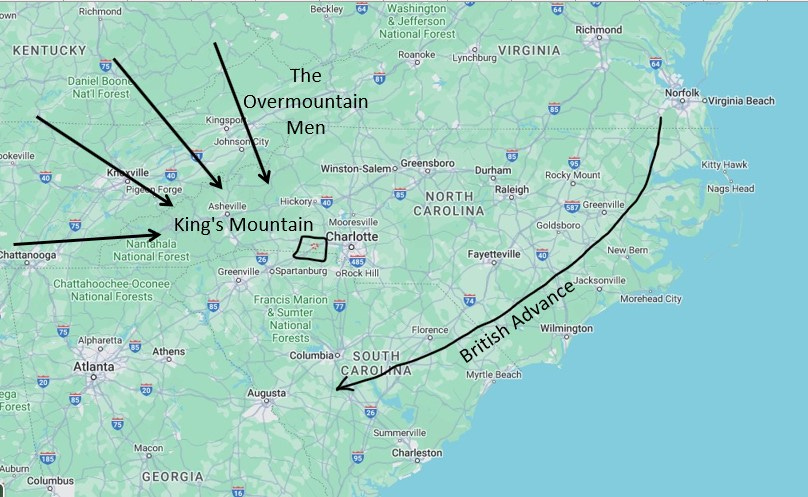

The British had been badly and surprisingly defeated at Saratoga in 1777 and again at Monmouth Court House in 1778. Their losses led to the French joining the war on the side of the colonists. Things were going badly for the Crown in New England, so their strategy pivoted southward.

Believing the southern colonies to be home to many Loyalists (Americans whose sympathies were aligned with the Crown), British General Sir Henry Clinton took his army into Virginia and North Carolina.

In short order, the redcoats rolled through the coastal south. Clinton’s victorious British regulars captured Savannah in 1778, Charleston in 1780, then easily took control of smaller South Carolina towns: Georgetown, Cheraw, Camden, and Ninety Six.

Brutality Reigns

After taking Augusta, Georgia, Clinton broke the back of the remaining Continental Army in the south near Lancaster, South Carolina, at the Battle of Waxhaws. At that May, 1780, engagement, British Lt. Colonel Banastre Tarleton ordered a cavalry charge on Continental foot soldiers.

The Continentals, seeing they were outnumbered and outclassed, threw down guns and attempted to surrender. Tarleton’s men massacred the helpless troops, killing or wounding 75% of the colonial force in a bloodbath that became known as the Waxhaws Massacre.

Banastre Tarleton was one of the real-life persons behind the fictional character Colonel William Tavington in Mel Gibson’s 2000 movie The Patriot. Banestre Tarleton and Patrick Ferguson were two of a kind.

Waxhaws became a rallying cry for outraged colonists. Thousands who had preferred to sit out the war, tending crops and minding their own business, were suddenly aroused. A deadly determination began to spread through the Appalachian hills.

“Bulldog” Ferguson

Oblivious to the gathering storm, Clinton returned to New York. He left Cornwallis to mop up the remnants of the South Carolina backwoods territory.

This would not end well for the British.

Cornwallis’ chosen instrument was Patrick Ferguson, the fiery, now one-armed Scotsman. His men called him Bulldog.

Ferguson, with no British regulars under his command, recruited local Loyalists on whom the Crown pinned much of their hopes. In various small skirmishes, Ferguson soon found he could not keep order among the provincials. They began to loot and plunder farms. They hanged men they suspected of Patriot sympathies. It was becoming a gang out of control.

Among the watching Patriot populace, outrage piled upon outrage.

Staying in front of this bloodthirsty assortment of men, Ferguson announced his intention to clean up resistance throughout the backcountry.

Flushed with the success of the tidewater campaign, and in particular the resounding British victories at Charleston and Camden, Ferguson made his public proclamation. He announced that if the colonials failed to cooperate with His Majesty’s forces, Ferguson would “march over the mountains, hang their leaders, and lay their country to waste with fire and sword.”

On hearing this news, back country American woodsmen listened in stony silence. And then, awakened, they began to move.

Words Mean Things

Ferguson’s challenge galvanized resistance from the Carolina backcountry and the Appalachian mountain range. Hardened woodsmen, accustomed to living off an unforgiving land, took notice. Word of the threat traveled from settlement to settlement and from home to home.

Men outfitted themselves with a long-familiar long rifle, powder and shot. They congregated in the Appalachians in what would become western Tennessee.

Hard Americans who had carved out homes and small farms from wilderness areas that today we know as Tennessee and Kentucky left their cabins and headed east. They marched 90 miles in 5 days to converge at Sycamore Shoals, North Carolina. Best estimates are that 910 armed men showed up, having no idea of the size of the enemy force.

The Reverend Samuel Doak, a Presbyterian bishop, urged the colonials forward in their reply to the British threat. His sermon to the men and his prayer for their venture has been preserved:

Go forth then in the strength of your manhood to the aid of your brethren, the defense of your liberty and the protection of your homes. And may the God of Justice be with you and give you victory.

September 26, 1780

Ferguson, receiving word of the growing resistance, collected his 1,125 Loyalists and encamped on a low tree-covered hilltop, King’s Mountain in South Carolina, a few miles from the North Carolina border. On the evening of October 5, 1780, they made camp. There they apparently planned to rest for a day before falling back to join the main body of Cornwallis’ force.

Plans often go awry. Unknown to Ferguson, his location had been observed by a colonial scouting party. Word was sent to Sycamore Shoals, and the wheels began to turn toward an inevitable confrontation.

The Overmountain Men

Who were these backcountry men who sought to challenge the most powerful military force in the world?

Their names are lost to history, although some identities no doubt live on in family lore, isolated stories of distant ancestors 5 or 6 generations removed.

The names we do have are of a handful of colonial militia leaders, prominent among them William Campbell, age 35. He had signed the Fincastle Resolutions, the earliest statement published in the colonies calling for armed resistance to the King.

Campbell and other leaders recognized their untrained, undisciplined army of backwoodsmen would not fight as a unit. It would be suicide to face the British on an open field.

The provincial colonists, under the command of various leaders, deployed around the perimeter of King’s Mountain. They were to fire on the Loyalist camp as they had opportunity, not waiting for a signal. Just open fire when you have a shot.

Campbell’s only instruction was: “Shout like hell and fight like devils.”

As the ragged and disorganized battle opened, only one Patriot leader was killed among the 28 militia men lost that morning. William Chronicle, 25 years old, led his men from the front, circling around to attack the northeast slopes of King’s Mountain. When firing began, he shouted to his troops, “Face to the hill!” and raced forward. He was dropped at close range by a musket shot.

The Battle

Earlier on the morning of October 7, Ferguson had anticipated the attack. Readying his forces, he arranged them in careful ranks at the edge of the mountain-top. Expecting the colonial advance from the woods below, he led multiple bayonet charges downhill, only to find nothing but a few random shots from very far away.

Redcoats began dropping around him, but in the thick woods, no targets were in sight. Ferguson led his men back uphill, then tried again with the same dismal result. He could not find an enemy who would confront him. This, he believed, was not the way wars were to be fought.

War should rightly be in the open, with ranks of disciplined, uniformed soldiers marching toward each other for a decisive battle.

Once again moving back uphill, Ferguson discussed the problem with an aide. They were some 300 yards from the nearest portion of forest, safe enough from musket range.

A bullet suddenly whizzed between the two mounted men, struck and killed a horse another 100 yards distant. The shot had traveled at least 400 yards and executed a perfect heart/lung killing shot on the horse.

Ferguson was in trouble.

The Difference was the Guns

All through the morning, Loyalist troops fell all around the mountain. The attackers could only rarely be seen. In the few pitched battles that allowed an exchange of fire, the vastly superior arms of the colonials became obvious.

The Pennsylvania long rifles, most manufactured at Lancaster, Pennsylvania, easily had a range exceeding 300 yards. Some accounts speak of accurate 1,000-yard killing shots.

The Brown Bess musket, widely used among the British, and which most of the Loyalists carried, were accurate to only 100 yards. The muskets fired 3 times as fast, but had no chance to reach distant targets.

Rifles are fundamentally different than muskets. Muskets have smooth bores; the round lead ball is flung out of the muzzle by the force of exploding powder, but lacks ballistics. A rifle, on the other hand, has grooves inside the barrel. The grooves twist the ball as it travels down the bore, spinning it like a football.

The spinning motion stabilizes the projectile, affording both distance and accuracy.

Facing a squadron of muskets at 100 yards is like facing a very powerful but inaccurate shotgun: The lead can go anywhere in your general direction. Facing a single rifleman at 300 yards will virtually guarantee a kill each time the trigger is pulled.

Ironically, Patrick Ferguson knew the difference in armament probably better than any man in the conflict that day. In the days before he lost his arm he had designed the celebrated Ferguson Rifle, a breech-loading flintlock.

The Pennsylvania gun was a muzzle loader, slowing the rate of fire to about 1 round every minute. The Ferguson could fire twice as fast and be just as accurate — but there were no Ferguson rifles with his men that day.

Leading yet another desperate charge downhill, Ferguson was shot from his saddle and died on the mountain. The remaining Loyalists surrendered. The battle had lasted barely one hour.

Aftermath

A handful of the Loyalist troops, whose crimes could be identified, were hanged. Of the over 1,100 who had begun the battle, 300 had been killed or wounded, three times the number of Patriot casualties.

About 600 Loyalists were taken prisoner. By the time they were turned over to intact Continental Army units, that number had dwindled to less than 100. The loss of the prisoners (due to escape or unauthorized parole) was a blow to colonial Army leadership, as they could have been used for prisoner exchange.

But the colonists from the mountains seemed to have had less interest in administering the aftermath of the battle than in winning it in the first place. After the victory was secured, the ragtag collection of unnamed and unrecorded backcountry fighters simply disappeared back into the forest.

One Loyalist account after the battle described the Overmountain Men: “like devils from the infernal regions… tall, raw-boned, sinewy with long matted hair.”

The message to the British was clear: the Overmountain Men, as this breed of Patriot came to be known, were not the citified Tidewater subjects who had been so easily conquered. This type of man was different: Determined, armed and deadly.

Cornwallis pulled his troops back into North Carolina, lost a series of demoralizing engagements led by Patriot General Nathaniel Greene, and a year later finally surrendered to George Washington’s forces at Yorktown.

Takeaways

As with any study of history, lessons — both good and bad — can be gleaned from the actions of those who have gone before. These lessons can be applied to how we manage business, career, and even personal relationships.

Here are a handful of insights from the Battle of King’s Mountain.

Hubris. This is a Greek word signifying exaggerated pride or self-confidence. Major Ferguson, designer of a firearm just as accurate as the Pennsylvania long rifle but capable of twice the rate of fire, was an expert in his field. He dd not lack confidence, courage or conviction. He was a superb physical specimen, overcoming the loss of his arm with incredible discipline.

What he lacked was the knowledge of his foe. His “fire and sword” proclamation awakened an enemy unknown to him. We can surmise that he was appalled when he met them.

Know who opposes you, and why.

Personal risk. People follow leaders who demonstrate that they are all-in. William Chronicle led from the front, urged his men forward and in many ways showed how the battle was to be fought that day. He financed this victory with his life. “Face to the hill!”

Success means putting it on the line.

Demeanor. The Loyalists, at first put on defense by Ferguson’s decision to dig in and wait for an attack on King’s Mountain, were demoralized by the very appearance of the Overmountain Men. When the “devils from the infernal regions” appeared from the tree line, confidence evaporated.

Look like a winner, in appearance and in actions.

Accurate Intelligence. When the colonial scouts located Ferguson’s encampment on King’s Mountain, they had the key to a victory. But the victory was not assured until their information had been relayed to William Campbell at Sycamore Shoals. Once advised, Campbell was able to devise and execute the plan.

Data is power, but only when delivered to the right actors at the right time.

Tools matter. The musket was highly intimidating when used by disciplined troops in European-style confrontations. In the woods of South Carolina, against an opponent 300 yards away, it was little better than a club.

Far outclassed by a Pennsylvania long rifle, much slower to load and in most instances firing a smaller bullet, King’s Mountain was no place for a Brown Bess musket.

Choose the tools suited to the contest.

Theological Contemplations

And I will close with this brief excerpt from Rev. Doak’s sermon, a clear reference to Psalm 144:1.

Your hands have been taught to war and your fingers to fight… Go forth!

In our own journey, there are worthwhile lessons for us here at the Battle of King’s Mountain, fought 244 years ago.

Whether our challenge is on a lonely hilltop against armed opponents, or in the arena of modern commercial competition, or in the daily effort to succeed in family and personal relationships, we may trust that God recognizes our struggle and leads us forward.

If you have found value (or maybe just entertainment) in this installment of our series on American Warriors, subscribe to The Alligator Blog. We would value your participation.

Curt

Share this post