December 13, 2023

“If you have to ask, you can’t afford it.”

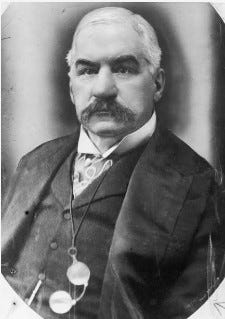

This saying, perhaps apocryphal, is attributed to the king of U.S. banking at the turn of the 20th century.

Here is the story of John Pierpont Morgan, 1837-1913, an American Titan.

It has been reported that Morgan routinely left his Wall Street office at the end of a workday, boarded his 240-foot yacht Corsair II at Battery Park and spent the night aboard, anchored in the Hudson River.

The yacht was regularly used to host dinner parties for New York’s great and powerful.

When an observer asked him what such a craft might cost, the tycoon offered the iconic reply. “If you have to ask, you can’t afford it.”

Such was the confidence and arrogance of America’s greatest financier of the Gilded Age.

Who was John Pierpont Morgan, and how did he gain his millions?

The beginning

First by inheriting it, and then by leveraging it.

Born into a banking family in Connecticut, Morgan’s history is the quintessential tale of the baby born with a silver spoon in his mouth. His early education was in various private schools on both sides of the Atlantic.

He learned to speak passable French and German, which later facilitated international investments. He spent time in both Europe and America, until focusing specifically on U.S. interests around 1858.

As a junior operative in a London bank, Morgan gained a familiarity with European securities.

War is good for business

At age 24, the Civil War broke out, and J. P. Morgan was in New York.

Never contemplating joining the military, young Morgan bought his way out legally. He paid $300, a small fortune at the time, to have another take his place. Instead of fighting, Morgan focused on the financial opportunities of the conflict.

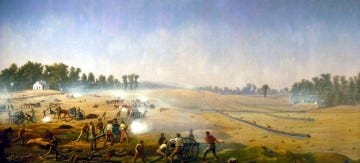

The war did not start well for the Union. The First Battle of Bull Run was a defeat for the North, and the army was suddenly short of arms. Morgan financed the acquisition of 5,000 Hall Carbines (rifled, .58) which were ultimately sold to the Union army at profits ranging from 100 to 700 percent.

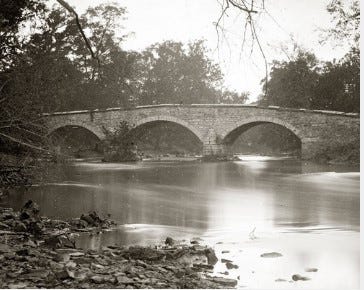

In early 1862, Robert E. Lee’s Confederate forces were on the move after their victory at the Second Battle of Bull Run. Lee moved north into Maryland, threatening the capitol.

Confronting him was Union General George B. McClellan, who advanced against Lee’s forces dug in at Antietam Creek. After a wide-ranging and bloody battle, Lee’s forces were driven back.

It was the most costly day in all of American history: more than 22,000 killed, missing or wounded.

Although the North suffered heavy losses and McClelland lost his job over this battle, the rebel army was turned back. Thus it was seen as a Union victory.

In many ways, Antietam set the stage for the following year’s encounter at Gettysburg. Antietam suggested that the Confederacy would not prevail, and Gettysburg sealed its fate.

Seizing the opportunity

The question no doubt was on Morgan’s mind: How could an unexpected Union victory be translated into monetary profit?

There were ultimately three answers to this question.

First, Morgan underwrote Union bonds. Suddenly the public believed the North would be victorious, and flocked to Morgan’s New York bank to invest their money.

Second, Morgan and a partner shipped over $1 million in gold specie to London, where the Union victory and the sudden offer created a spike in the price. Morgan sold at a profit.

Third, he seemed to have no scruples about whose money he would handle. A Confederate sympathizer with extensive investments decided to liquidate all his Union holdings and re-invest the cash in European securities. Morgan, with his background in the European market, handled the trades.

The rise of industry

In 1871 Morgan joined with Anthony J. Drexel. The firm began to specialize in financing industrial ventures. New manufacturing practices were being widely embraced, and capital was needed.

Drexel Morgan & Co gave their attention particularly to the railroads. With the increase in manufacturing came a heightened necessity to ship goods to market. The new company moved aggressively to finance new opportunities.

After the death of Drexel in 1893, the firm was renamed J. P. Morgan & Company. Morgan’s brand became a household word.

1893

Morgan’s father had passed in 1890. With his death, and the death of Drexel three years later, J. P. Morgan became the most influential banker on both sides of the Atlantic.

The Panic of 1893 began in London and spread to the New World. Americans traded in their paper dollars for gold and the economy contracted. Hundreds of banks failed, unable to make good on loans. Depositors were left without funds.

By 1895, the U.S. Treasury was nearly out of money. Grover Cleveland’s presidency was threatened by the crisis, and, in Morgan’s estimation, the administration’s response had been ineffective.

Congress refused to issue bonds in order to buy gold. Because, politics. Cleveland lacked the political capital to persuade them, and a default was near.

Morgan traveled to Washington and arranged a face-to-face meeting with the President.

In the meeting, Morgan pointed out, first, that while the Treasury department had only $9 million of gold on hand, there were warrants on the street for $12 million. As soon as they were presented, the United States would default on its debt.

Second, Morgan had researched previous legislation related to U.S. government investment in gold and silver. He had found a Civil-War-era statute adopted in 1862 at a time when the Union government was desperate for hard currency.

The act authorized the government to issue bonds, without congressional approval, for the purchase of gold coin in a way that would be “advantageous to the public interest.”

That small chunk of legislation allowed the Cleveland administration to circumvent Congress and issue bonds directly. The U.S. bought $60 million of gold coin from Morgan (and the investors Morgan rounded up), and the crisis was averted.

There was political fallout for Grover Cleveland, and, just as his first term ended with him not being returned to office, so did his second.

1907

Once again there was a financial crisis. (This was not unusual. There was a serious financial crisis in the U.S. in every decade after the Civil War.) Panic selling crashed the New York Stock Exchange, people drained their bank accounts of paper currency to buy gold, and once again Treasury stocks were depleted.

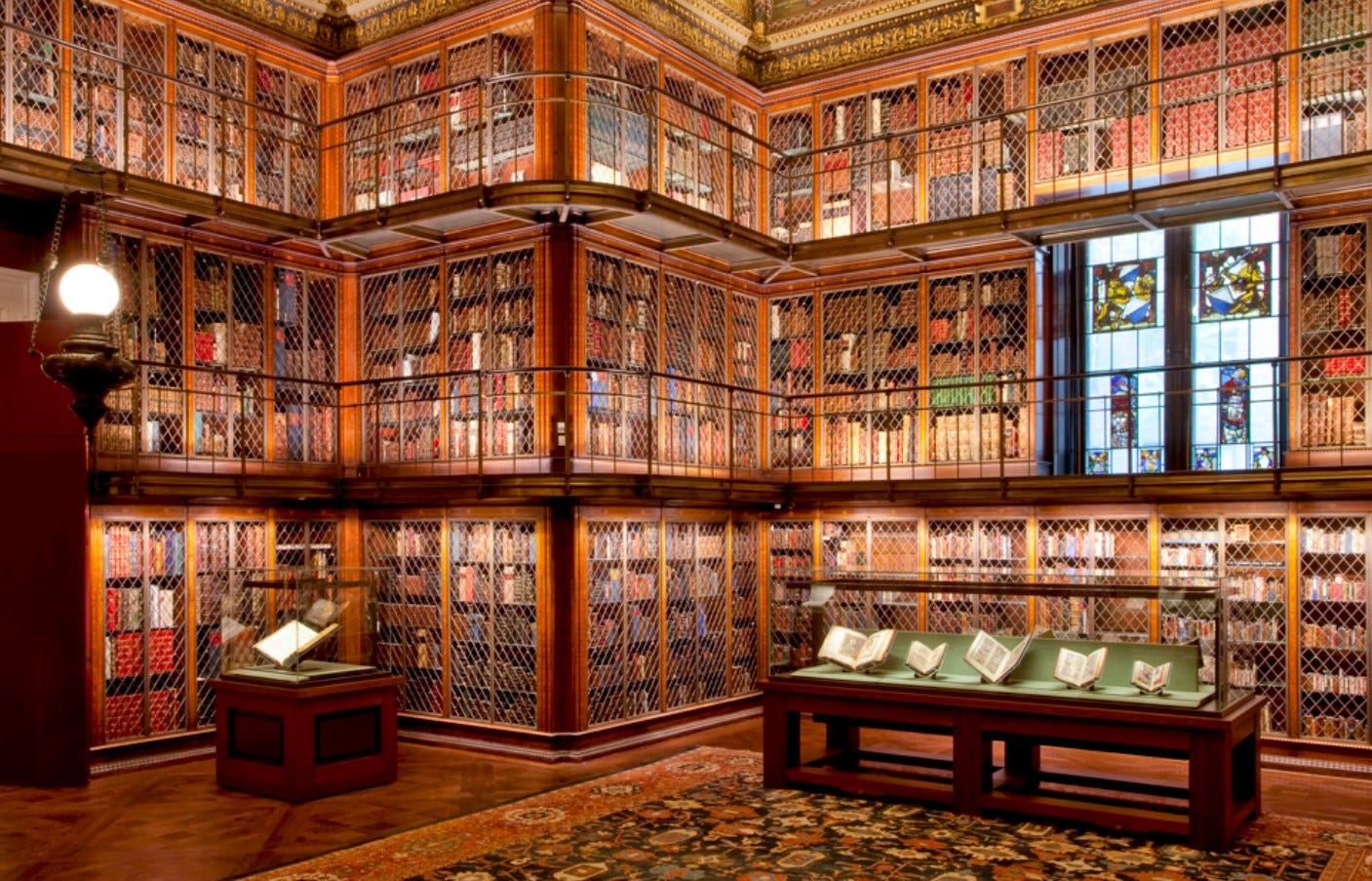

On this occasion, the 70-year-old J. P. Morgan traveled to his New York City office and began working his connections. He arranged a large meeting in his library of every prominent banker in the City.

With the door locked so that no one could leave, he required each participant to commit underwriting a loan to the U.S. government — in effect, purchasing U.S. Treasury bonds — which they would then sell to their banking customers.

There were no dissenters, probably because everyone understood that if they resisted J. P. Morgan, they would shortly be out of business.

It was a strong-arm tactic which no one else in America could have pulled off.

In the wake of this, the panic was calmed. The bankers sold the bonds, Teddy Roosevelt claimed victory… and Morgan was investigated by Congress for his disproportionate influence over financial markets. Six years later Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act.

Life and times

So: Was J. P. Morgan a hero or a villain?

Like most of us, the answers are probably Yes and Yes.

He presented an intriguing figure, apparently guided by principle. It was just a question of what those principles were.

His rejection of personal participation in the Union Army gives one pause. Somebody had to go fight, but Morgan apparently did not even consider it. He had money and could buy his way out. So he did.

During the congressional inquest after the 1907 incident, Morgan cited his commitment to character and moral responsibility. If he saw a conflict with his lack of war service, it is not apparent.

But there was an unusual level of commitment that I find surprising and touching.

Consider that Morgan was married twice. First to Amelia Sturges in 1861. Amelia suffered from tuberculosis, so much so that J. P. was obligated to physically carry her to the drawing room for their private wedding ceremony. She died only 4 months later.

His second marriage was to Frances Louisa Tracy, who gave him 4 children.

Upon Morgan’s death in 1913, his estate was worth $80 million ($2.3 billion in 2022 dollars).

Takeaways

What do we draw from the great financier? (Besides the fact that being born into wealth gives you a leg up on everyone else.)

Every crisis includes an opportunity. Without doubt, the American Civil War launched J. P. Morgan in a way nothing else could have. The defeat at First Bull Run meant the Union needed more guns. Whether Morgan was an unscrupulous war profiteer or a patriotic financier, the fact is he identified the necessity created by the crisis and met the need.

Every enterprise needs something. New manufacturers needed cash; wholesalers needed freight arrangements; the U.S. Treasury needed bond underwriters. This observation is applicable to every business, not just finance.

Early adopters are rewarded. Morgan moved into railroad interests about the time of the completion of the first transcontinental line. He observed the coming shape of America and used his asset base — including his investment experience — to move it forward.

Know your facts. Morgan probably understood the Civil War law giving the Treasury Department the freedom to purchase gold coins better than anyone in the Treasury Department. Money was his game, and he had learned it as well as anyone in the world.

Use personal intervention. In both 1893 and 1907, Morgan personally got on a train and traveled (to Washington and to New York) so that he could influence key decisions by force of personality. A personal appeal carries a great deal of weight.

Theological Contemplations

Mark 8:36 What good is it for someone to gain the whole world, yet forfeit their soul?

As is the case with most of the American Titans, little is known of J. P. Morgan’s faith profile. His grandfather had been an Episcopal priest, and Morgan himself was a lifelong Episcopalian.

As one would expect, Morgan supported the church financially. However, his faith may have gone much deeper than that. He was often observed by the clergy at St. George’s Episcopal Church to visit the sanctuary mid-week, sitting by himself and singing hymns quietly.

Perhaps there was a depth to his spiritual life that we simply do not know.

Morgan’s father, J. S. Morgan, once wrote to his son: "Remember that there is an Eye above that is ever upon you and that for every act, word, and deed you will one day be called to give account.”

Words which we would all do well to remember.

And that is the story of J. P. Morgan, an American Titan.

You can find the complete set of 12 profiles of the American Titans at www.alligatorpublishing.com/americantitans.

To get the full benefit of The Alligator Blog, sign up for the free newsletter. If you are already a subscriber, upgrade to a paid subscription to support the work. Thanks for joining us!