October 4, 2023

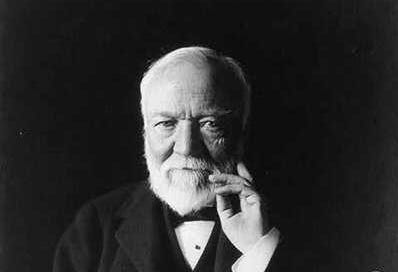

Andrew Carnegie: From Railroads to Philanthropy

Railroad Interests

Andrew Carnegie was born in 1835 at Dunfermline, Scotland, into a hand weaver’s home, where their one-room house was shared with another family. Seeing a future of nothing but poverty and likely starvation in the old country, his father borrowed from relatives and took his family to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. At age 12, young Andrew obtained work as a “bobbin boy” in a cotton factory, run by a fellow Scotsman, changing spools of thread 6x12 (6 days a week, 12 hours a day) for $1.20 a week.

Things began to look up when he secured a job as a messenger boy for the Pennsylvania Railroad Company.

Carnegie became intimately familiar with the operations of the railroad industry. He was clever, learned Morse code by ear, and was promoted to telegraph operator, responsible for coordinating train schedules.

The railroad was interesting, but he had his sights on something even bigger.

Big Steel…

In the mid-1870s, around age 40, he invested in the iron and steel industry, forming partnerships with various industrialists. Notably, he established the Edgar Thomson Steel Works in Braddock, Pennsylvania, which marked his foray into steel manufacturing.

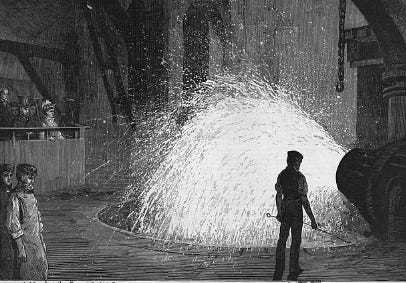

The Edgar Thomson business employed the new Bessemer steel process. As early as 1854, Henry Bessemer (in England) discussed the need for better artillery with Napoleon III at the outbreak of the Crimean war. Big guns were then made of iron, of poor quality and prone to breakage. Bessemer pioneered an industrial-level process, used for centuries in China and Japan on a smaller scale, of removing impurities from molten iron with forced air.

Bessemer licensed the process to U.S. interests, who built a factory in Troy, New York. By this time, Carnegie was an investor in the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, and owned the Keystone Bridge Company. His businesses were all about steel, and when he became aware of the Troy operation he latched onto the opportunity. He eventually funded 11 different mills to manufacture steel.

In 1873, steel cost $100 per ton. Within two years, Carnegie’s developments using Bessemer’s process had cut the price to $50. By 1890 it was at $18.

…Helped by Big Rail

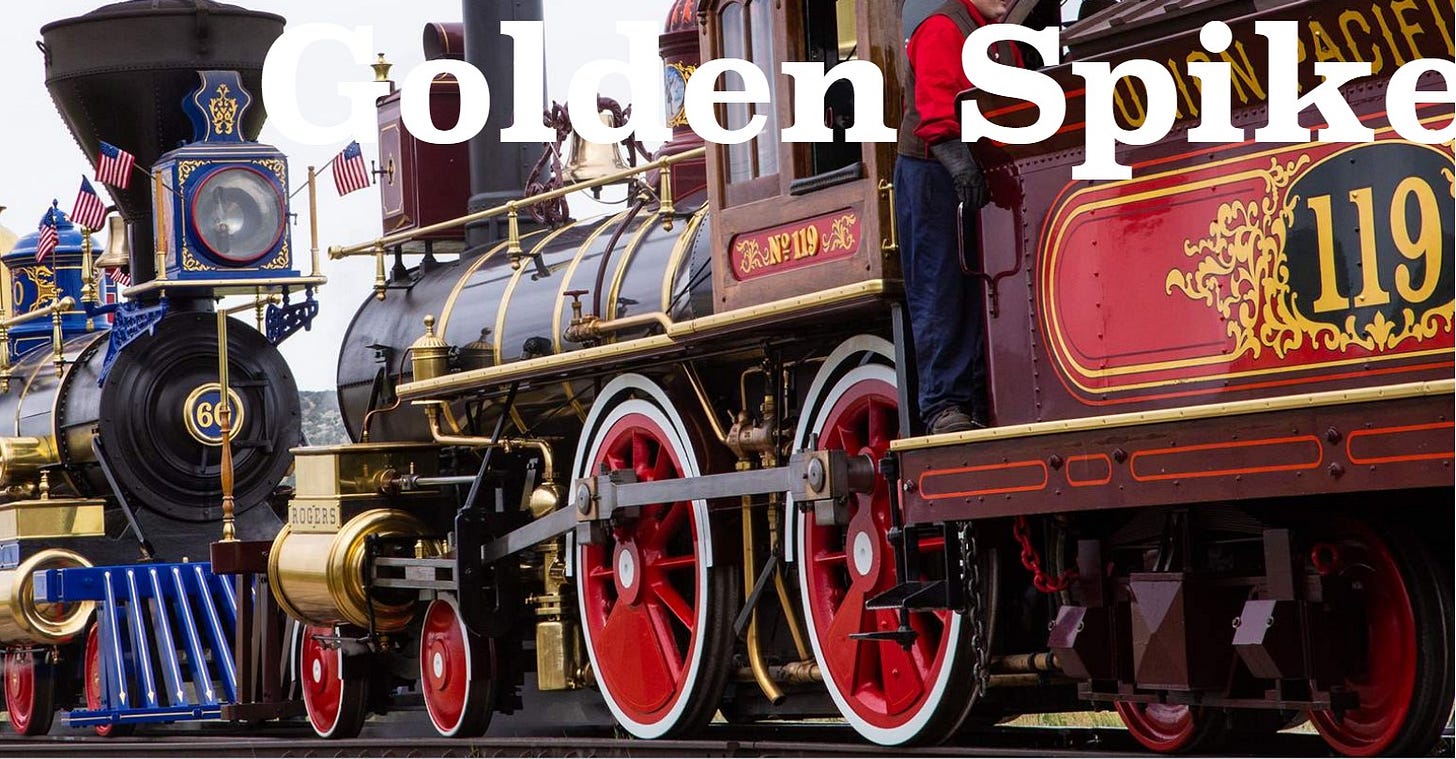

What Carnegie gave up in price per pound he more than made up for in volume. Total U.S. output in 1870 was 157,000 tons of steel per year. With the sudden development of railroads using higher quality steel at a lower price, production by 1910 was 26 million tons.

Recall that the golden spike that completed the first transcontinental railroad was driven at Ogden, Utah, in 1869. Freight was suddenly a coast-to-coast business.

Prior to this, a stage trip from St. Joseph, Missouri to San Francisco took 25 days travelling 24 hours a day at a ticket price of $200. After the rail line opened, the entire trip took one week and cost $20.

And you could ship your tractor along if you wanted.

A journalist actually did that trip on the stage coach, never stopping overnight, then wrote about it when he regained his sanity. Wish I remembered where I read that.

The steel business: Higher quality, lower price, faster production, booming demand… somebody is likely to get rich off this combination.

Vertical integration is the practice by a single business of bringing all aspects of production in-house. Carnegie acquired iron ore mining interests for raw material, coal mines for fuel, steel mills for production and railroad interests for distribution. He was also his own best customer, purchasing finished steel products for railroads and bridges.

Carnegie Steel Corporation became one of the most profitable companies in the world.

J.P. Morgan rides in

It was profitable enough that it drew the attention of J.P. Morgan in 1901. This, incidentally, was the same year Morgan successfully fought off Edward Harriman’s attempted takeover of the Northern Pacific Railroad, and crashed the New York Stock Exchange.

Morgan was a busy man in 1901.

Morgan orchestrated the merger of Carnegie Steel Corporation with several other steel companies. These included Federal Steel Company and National Steel Company. The United States Steel Corporation was created from the combination.

The merger resulting in U.S. Steel formed the world's first billion-dollar corporation, and Carnegie promptly sold out his share for $300 million cash.

Carnegie turned his back on the business, over loud protestations from those who claimed he was abandoning the suppliers, customers and employees who depended on him.

Having made his millions — 300 of them, in fact — he defended his decision to sell, choosing to focus his wealth in his remaining years on philanthropy and education.

Philanthropist Extraordinaire

All these American Titans tried to out-do each other in who could give away the most money. I think Carnegie won that game, but it was nice to have them all competing.

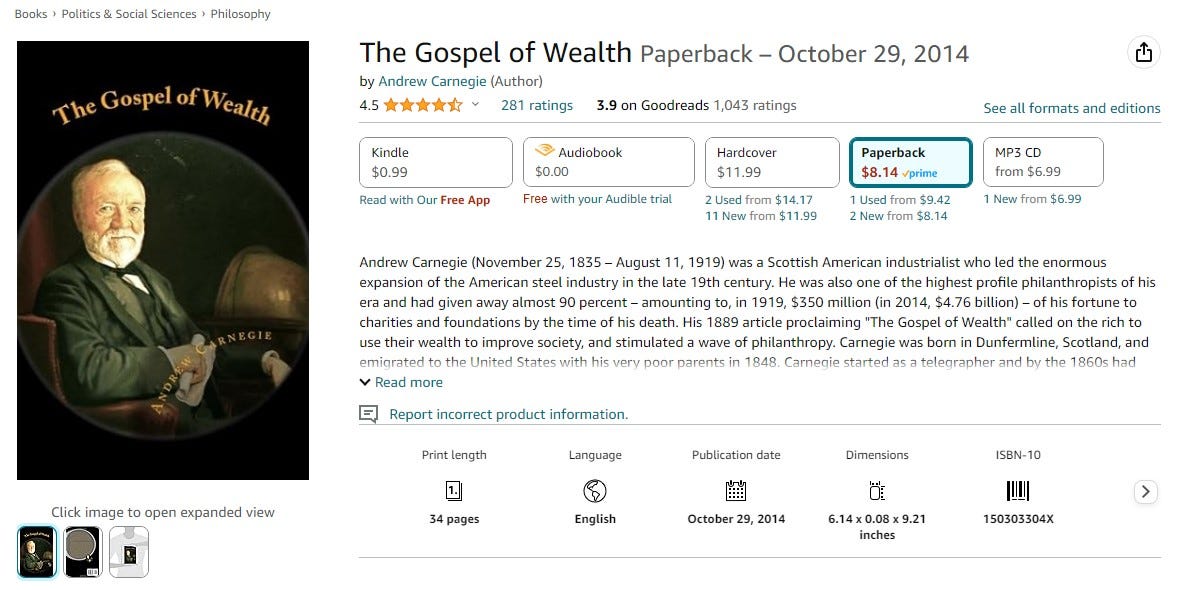

Carnegie subscribed to the philosophy of the "Gospel of Wealth," which suggested that those with substantial wealth should use it to address social issues and improve the lives of others.

His book is still available today.

I don’t know what the interaction of this gospel with the actual Gospel was, but I would never say the philanthropy was a bad thing.

One of Carnegie's most significant philanthropic efforts was the construction of libraries across the United States and other parts of the world. He believed that access to knowledge and education was essential for personal and societal progress. He funded the building of 2,500 public libraries, providing free books to communities.

You wonder what he would have done with high speed internet.

Additionally, Carnegie contributed to the development of educational institutions such as Carnegie Mellon University, the Carnegie Institution for Science, and the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. His donations facilitated scientific research, higher education, and the general dissemination of knowledge.

War and Peace

In addition to his business pursuits, Andrew Carnegie also held strong views on foreign affairs, particularly concerning peace and diplomacy. He was a passionate advocate for international peace and disarmament, and he used his wealth and influence to promote these ideals.

Prior to 1910, Carnegie saw war in Europe coming. He loathed the prospect and enlisted Theodore Roosevelt, fresh from the African safari Carnegie had financed, to appeal to Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany to avert armed conflict.

Carnegie urged Roosevelt to offer a multi-million dollar payment (read: bribe) to the Kaiser to stop the move toward war. Roosevelt refused to carry the message, believing it would be ineffective.

Roosevelt was probably right. Egos were at stake in Europe, and no amount of money would make them go away.

Theological Contemplations

For all his business savvy, Carnegie apparently misunderstood a fundamental lesson. We are of a fallen nature that is borne of sin and that, left unchecked, pushes us further into sin.

Zechariah 4:6 ‘Not by might nor by power, but by my Spirit,’ says the Lord Almighty.

The millions of dollars that Carnegie amassed could not avert world war. He did great good things, to be sure, but seemed to operate from a worldview that said applying enough money could fix problems.

And it truly can… but not the problems stemming from sin in the heart. That is not fixed by might, not by power, not even by huge sums of cash, but only by the Spirit of God.

That our souls might be eager for such a portion of His Spirit.

Have a good week!

If you’re new here, subscribe for free to get this blog delivered to your inbox regularly each week. Upgrade to an annual paid subscription to help keep them coming. Read about the free merch, and the discounted merchandise suitable for your Christmas shopping at www.alligatorpublishing.com.

Curt

Share this post