Deepest Shipwreck Ever

The wall-to-wall coverage of the Titan submersible lost at the wreck of the Titanic ocean liner prompted a flood of unasked links to other shipwrecks as I surfed last week. One name caught my eye.

The USS Johnston was lost in 1944, and I stared at the screen a moment before recalling it was a U.S. Navy destroyer, heroically engaged in the Battle off Samar during the enormous spectacle that was the Battle of Leyte Gulf, WW2.

When U.S. General Douglas MacArthur sought to re-take the Philippine Islands from Japanese forces on his way to invade their homeland, the logical place for a beachhead was from within the protective arms of Leyte Gulf, a body of water roughly half the size of Chesapeake Bay.

MacArthur’s forces made the landing and, after putting ashore, were guarded by American naval forces against counterattack by Japanese warships.

The U.S. Navy force in the Gulf was a small one with an unintimidating name: Taffy-3 was comprised of six escort aircraft carriers (small ships with only 16 planes each), three destroyers (DD) and four smaller destroyer escorts (DE). There were other Navy assets only a few hours away.

It was unlikely the enemy could reach into Leyte Gulf, as they would have to navigate the treacherous San Bernadino Strait in the western approaches to the Philippines, threading their way through a complex chain of tiny islands. Moreover, they would have to accomplish this at night because U.S. aircraft ruled the day.

At 6:35 am on October 25, 1944, the unlikely occurred.

Japanese Admiral Takeo Kurita sailed out of the morning mist with 4 battleships, 8 cruisers and 11 destroyers. The Yamato was among them, one of the super-battleships Japan had commissioned; it was the largest ship in the world.

The size of ships is expressed in terms of how much water they displace, in other words, how heavy the ship is. Yamato was a 64,000-ton ship. The entire Taffy-3 force, 13 ships in all, including the aircraft carriers, displaced 60,000 tons. Yamato by herself was larger than the complete Taffy-3 squadron; and there were 20 other warships besides Yamato in the Japanese fleet that day in Leyte Gulf.

The first Native American to ever command a U.S. Navy fighting ship, Commander Ernest E. Evans, a Cherokee Indian from Muskogee, Oklahoma, led the tiny destroyer force of Taffy-3 from the bridge on Johnston.

When Johnston was commissioned at Seattle in 1943, 12 months before meeting her destiny in The Philippine Islands 6,000 miles distant, newly minted Commander Evans had declared: “...This is going to be a fighting ship. I intend to go in harm's way, and anyone who doesn't want to go along had better get off right now." Prescient words.

For two hours on an October morning exactly one year later, he made naval history with incredible bravery and fortitude. After striking with all the torpedoes carried by the DDs and DEs, he continued to engage battleships literally 10 times his size. His 5-inch guns were tiny, no match at all for the massive force he confronted. Johnston took hit after hit.

Naval aviators from the escort carriers got into action. They sortied and dove on the enemy ships. Unknown to that enemy was that the Americans were armed only with anti-personnel bombs suitable for supporting the beachhead from the previous day. They had no armor-piercing ordnance that was required for sea battle.

The aircraft were also low on ammunition for their wing-mounted guns.

The shortages did not stop the pilots from engaging, and their bluff paid off. Japanese ships scattered when Navy aircraft began to dive. Some Americans actually made dry bombing runs; no bombs, no bullets, just a screaming Grumman F6F Hellcat diving out of the clouds. Battleships, cruisers and destroyers turned frantically, trying to escape the bombs that never came.

Back on the Johnston, Evans saw a contingent of enemy ships approach Gambier Bay, an American escort carrier already damaged by Japanese guns. This was one of the assets Evans was charged to protect. Without hesitation, he pushed his stricken vessel – by now operating on half power and with only two of his 5-inchers still in action – into a classic naval maneuver called “crossing the T.”

As the enemy steamed ahead, Johnston intercepted them and exposed their approaching bows to his broadside.

In the wind-powered days of sail a hundred years earlier, this meant your entire cannon broadside could fire on the ship approaching, whereas he could return fire with only his bow-mounted guns. (Nelson crossed the French T at Trafalgar, 1805, resulting in a huge British victory.)

Johnston’s broadside was not much, but it drove the enemy off course, drew their fire, allowed the escort carrier temporary escape and brought the wrath of the attack force down on herself. She suffered a direct hit from a three-shot salvo of Japanese 14-inch guns and was mortally wounded.

Propulsion gone, guns knocked out and the warship rapidly filling with seawater, Commander Evans gave the order to abandon ship. Half the crew went down with her at 9:35 am, the Captain among them.

The ferocity of the defense put up by Taffy-3's destroyers under Evans’ command, and the challenges of ship identification with binoculars from 15 miles away, led Kurita to believe he was facing a much larger force of cruisers rather than destroyers, and full-sized fleet carriers rather than escort carriers. He was convinced he faced an overwhelming American force. In truth, no other assets were on the way, owing to poor communications among the Americans.

With incredulity, the remaining Americans saw Kurita break off the attack. He ordered his force to withdraw back through the San Bernadino Strait, having lost 3 of their cruisers sunk by the inferior American task force.

The U.S. lost Gambier Bay, the only U.S. aircraft carrier sunk by direct enemy surface ship fire in WW2, and three of the 7-ship destroyer force: Hoel, Johnston and DE Samuel B. Roberts. The remains of Johnston and Samuel B. Roberts were discovered in 2021 lying 20,000 feet down in the Philippine Trench, some 8,000 feet deeper than Titanic. Roberts rests slightly deeper than Johnston, making her the deepest wrecked ship in the world.

For his actions that day, Commander Evans (Naval Academy, Class of 1931) was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

An engaging snippet of this battle can be viewed in the 1985 CBS mini-series Space, based on a James Michener novel of the same name. James Garner plays Ernest Evans for about one minute at the beginning of episode one.

The Takeaway

So... what do we derive from the story of Ernest Evans and the USS Johnston? How about this: We do not always get to choose the trials we face, only how we face them.

Choose your path, decide ahead of time, verbalize the commitment in the presence of others, and when the challenge comes, don’t think. Just act.

Of such decisions are nations built. Or communities. Or families.

Merch is here!

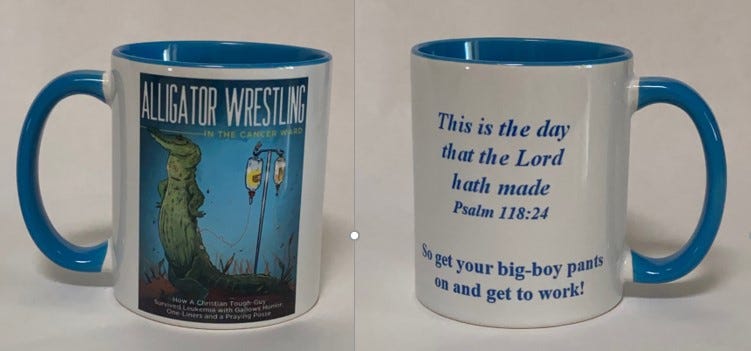

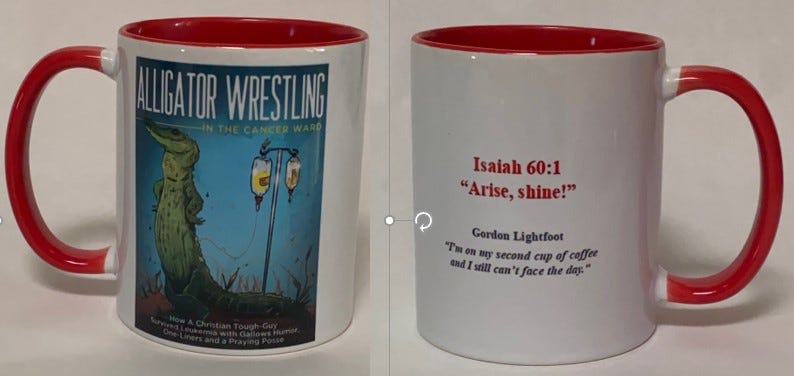

And now for the important stuff. I deciphered the merchandising interface (like reading tea leaves, grrr!), and now you can order as many or as few of the Alligator Wrestling ceramic coffee mugs as you wish.

Also, see the Alligator Wrestling Travel Mug and the Wine Tumbler.

Free shipping on all!

https://www.alligatorpublishing.com/store

The paperback book (and links to the audio and eBook versions) is also available there: Alligator Wrestling in the Cancer Ward: How a Christian Tough-Guy Survived Leukemia with Gallows Humor, One-Liners and a Praying Posse.

Pants-on Travel Mug

Spirit Wine Tumbler

Pants-on Blue

Heroes Orange

Arise Red

Coffee Black

Bully Yellow

Trials Pink

Collect all 6!

Verse for the Week

Revelation 20:12-15 (abridged) And I saw the dead, small and great, stand before God… And the sea gave up the dead which were in it… And whosoever was not found written in the Book of Life was cast into the lake of fire.

Well… what a sobering thought. Whether our works are small or great, it seems that they are trumped by that Book of Life, and the names written therein.

Perhaps we should think on these things.

Curt

Share this post