Henry Ford, eventually known for revolutionizing factory production with the assembly-line, changed the world with his Model T motorcar.

Unlike some stories of great influencers of history, who stumbled their way into greatness, Ford set out for greatness. From very early in his career he was determined to automate the country.

And he did.

When I was in 7th grade, I made myself a brief laughingstock with an answer to a philosophical question a teacher had posed:

His Q (as nearly as I recall): What was the development that changed America from a farm society to a mechanical society?

My A: The internal combustion engine.

Well… that was so wrong.

The answer he was looking for was The Industrial Revolution. Which maybe I would have known if I had read the assigned chapter in the book for that week: “The Industrial Revolution.”

For young Ford, time and circumstance joined with his personal energy to create a climate ripe for development. He exploited the combination, became both respected and despised, and made himself and many others wealthy along the way.

He changed America in a way few others have.

Born in 1863 on a farm near Dearborn, Michigan, exactly 6 years after his father had emigrated from Ireland, Ford's journey from rural life to industrial success reflected the larger background of national transformation from agriculture to industry.

When that transformation of America was complete, Ford was not really convinced he liked the shift.

Early fascinated with engineering and all things mechanical, Henry Ford made a home-built steam engine to power a small locomotive for his farm. Spending time in machine shops in Detroit exposed him to the miracle of internal combustion, and by 1896 he had produced his first horseless carriage.

The Horseless Carriage

The Quadricycle was a simple and spindly affair, basically a buggy with bicycle wheels, a steering tiller and a tiny engine.

Other developers of his time treasured their first automotive creations. Ford unromantically sold his to finance his next model.

Ford believed that if he could build a successful race car, he could attract capital. With C. H. Wills, another motorcar enthusiast, Ford began work on a two-cylinder racer. At Grosse Pointe, Michigan, Ford won his first race — driving the car himself — in October 1901.

A month later he organized the Ford Motor Company with 5 investors behind him. What he knew was the race car, and he fought to make it better. He and Wills continued to refine the product. This disgusted the investors who were looking for serious profits from a much, much wider consuming population.

The wealthy investors found Henry Ford to be single-minded, closed to advice, and cantankerous; thoroughly exasperating. After four months of infighting, Henry simply quit the company that bore his name.

Barney Oldfield

Moving the race car operation to a new location, Ford and Wills continued development, and in 1903 Barney Oldfield won a race at Indianapolis in Ford’s car named “999.” Incredibly, Oldfield pushed it to the unheard-of average speed of 59 mph over 5 miles.

Capital began to flow in, and Ford finally leveraged lessons from 999 into passenger automobiles.

After a few other alphabetically-named efforts, Henry Ford introduced the Model T in 1908.

The price was $850 and required 3 men 12 hours to produce one vehicle. This was an astounding feat, but the price made it a rich man’s toy, and a single car per day would never arm the masses with transportation. Having begun the chase, Ford was determined to find a way to reduce the price to a level where every family could own one.

He had to find a way to build faster.

Enter the production line.

Outrageous Innovation

Teams of workers, Ford realized, spent too much time unpacking and arranging the parts required to assemble the vehicle. If workers could be rearranged so that they performed only one function, and if the parts were suddenly to appear right beside their work station, they could work quicker.

And if the unfinished car came to them, instead of them moving to the unfinished car, yet more time could be carved out.

In 1913 the Highland Park plant installed a continuously moving assembly line where a fixed motor pulled the automobile chassis along by a rope. With other tweaks, in a year the time to produce one vehicle had dropped to 93 minutes. The magneto, engine and transmission all fell to the assembly-line concept, each with their own line, and within a few years, multiple sub-assemblies funneled together to allow the production of a finished Model T.

The key to this early mass production effort was standardization. It was during this time that Ford uttered the line that made him famous in business marketing lectures for the next century:

“Any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants, so long as it is black.”

The rapidity of the moving assembly line created other problems. Many car parts had been sub-contracted to local businesses, who found it impossible to keep up with the advancing pace.

Ford began to experiment with bringing various production activities in-house, as Carnegie had done before him in the steel business. Vertical integration was the order of the day, and soon Ford had bought a rubber plantation in Brazil, coal mines in Kentucky, and iron ore mines in Michigan. He added ships, railroads and timberland.

Ford acquired, fabricated and assembled his own parts.

By 1927, a load of iron ore could be delivered in the morning, and 28 hours later a complete Model T would roll off the line. Producing 10,000 cars a day by that time meant that, somewhere in the Ford universe, new Model Ts were created at the rate of one car every 9 seconds.

Incidentally, the Model T was not the only invention using an engine. Ford also ventured into aviation with the Ford Tri-Motor aeroplane.

Although left behind, his farm roots were not forgotten. He also created the Fordson tractor.

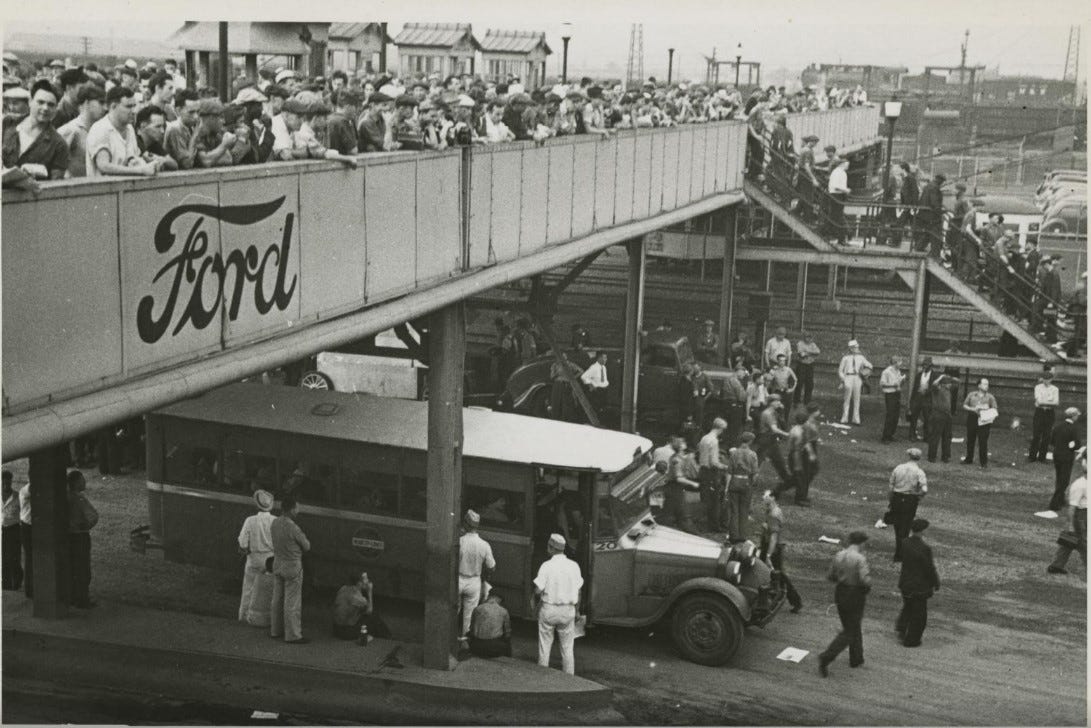

Labor Problems

With all the workers integrated into various assembly lines, the speed of work was dictated by the speed of their line. Work, in past years requiring skilled labor, become more rote and monotonous, along with the ever-present urgency to serve the line.

Unrest grew and at the same time a new dimension of immigrant labor altered the dynamics of the factory. By 1914, only 29% of the 14,000 employees at Highland Park were American-born. Europeans and Russians filled out the ranks, many without English.

Both the Industrial Workers of the World and the American Federation of Labor sought to organize the people.

In response, Ford doubled the pay. Where wages had been $2.40 per day, it suddenly leaped to $5.00.

In doing this, Ford had not only created the modern production line, he created the modern middle class.

With the increased pay came Ford’s uniquely heavy-handed social engineering. The nominal rate remained $2.40 a day. The additional $2.60 was paid only when a worker met the approval of Ford’s Sociological Department, home visits to ensure the worker’s lifestyle met company expectations.

The extra pay was disqualified if the home was not kept tidy, if the wife worked outside the home, if there was gambling or drinking in evidence, or if the employee failed to contribute to a savings account.

Despite the wage increase, costs fell as production soared. By 1916 the price of a new Model T was $360 and sales volume was three times that of the pre-production line. In time, the price fell to $290. When the car was discontinued in 1927, there were 15 million on the road.

The workers may have been bored, and may have lived in their own neighborhoods, and may have resented the social intrusion, but most of them had Model Ts.

In the heyday of stock market growth in 1929, Ford raised the weekly wage again to $7. Then the Depression came, and he cut it back to $4. Resentment exploded, and the United Auto Workers organized the labor force by vote in 1941.

The Man and His Beliefs

Henry Ford, like many of the American Titans, was a restless dynamo. Quick to jump to conclusions, he could not easily — or ever — give up his beliefs. He is as well-known today for his anti-Semitism as for his production line. He is the only American complimented by name in Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf.

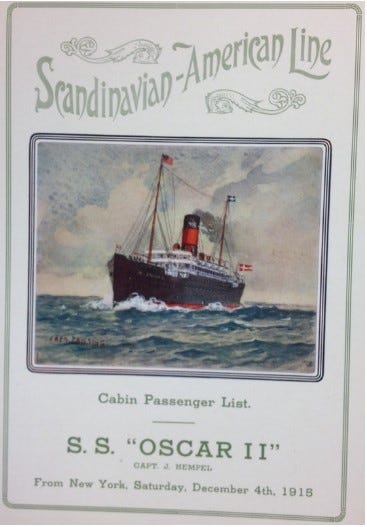

During World War I, Ford recognized and despised the war profiteering he observed in other American industrialists. Altruistically, he was a pacifist and sincerely wanted to end the war in Europe.

To this end, in 1915 he organized a peace conference in Sweden. He rented a passenger liner— dubbed “The Peace Ship”— and took a large delegation of like-minded activists along with him.

Perhaps inevitably, the movement failed, in large part, and ironically, due to infighting among the delegates.

Ultimately, the war profiting which Ford held in such disdain came home to him. There was such publicity surrounding his failed peace initiative that his name and his Model T became household words throughout Europe. Post-war sales poured in.

Theological Contemplations

A smattering of Bible passages come to mind as we consider this American Titan Henry Ford.

Deuteronomy 8:18 But remember the Lord your God, for it is he who gives you the ability to produce wealth…

Proverbs 14:23 All hard work brings a profit, but mere talk leads only to poverty.

Ecclesiastes 9:10 Whatever your hand finds to do, do it with all your might…

And of course, the Parable of the Talents, Matthew 25:14-30, which in part reads:

14-15 …It will be like a man going on a journey, who called his servants and entrusted his wealth to them. To one he gave five bags of gold, to another two bags, and to another one bag, each according to his ability. Then he went on his journey.

19 …the master of those servants returned and settled accounts with them.

21 Well done, good and faithful servant! You have been faithful with a few things; I will put you in charge of many things. Come and share your master’s happiness!

26-27 You wicked, lazy servant! …You should have put my money on deposit with the bankers, so that when I returned I would have received it back with interest.

Henry Ford, more than anyone else, transformed agricultural and industrial work into automated systems that harnessed machines to amplify muscles. The term for this is innovation.

The Scripture commends our investment in useful work and disdains the lazy.

On that score, Henry Ford’s creative manufacturing processes are unrivalled in leveraging productivity. With all his faults — and they are grievous, flagrant and numerous — his determined focus on industrialization moved the world forward. His personal energy and resolve raised across-the-board standards of living like no other has.

As with any human endeavor, sin was never far away. With the development of the production line came not only wealth and improved living conditions but discontent and unrest.

Sin, a result of the Fall, taints every human activity.

Ford recognized his place in history. The transformative effect of the modern production-line factory was not lost on him. In a conversation with an associate about “the modern age,” Ford snapped, “Young man, I invented the modern age!”

May we gain the wisdom to live productively in this world with an eye to the next.

Curt

Share this post