November 8, 2023

We find the stories of the Titans of America’s Gilded Age, 1877-1901, captivating. Those were the visionary capitalists who made America an industrial powerhouse and made themselves wealthy along the way.

Some we would call good men with sterling qualities: George Westinghouse, Gustavus Swift, Edward H. Harriman.

Others get mixed reviews, because of character flaws: Henry Ford, J. P. Morgan, Cornelius Vanderbilt.

And some were downright scoundrels, with almost no redeeming qualities. They were truly bad guys who managed to take advantage of the right people at the right time and enrich themselves at someone else’s expense.

Perversely, I find their stories equally compelling and delightful to read.

Jay Gould, 1836-1892, is one of those. A cad of the first order.

Gould’s father was a farmer. As a boy, young Jay had to drive cattle into the barn both morning and evening, where his sisters could do the milking. He walked barefoot and frequently got thistles in his feet.

He wanted nothing to do with farming. He was, however, interested in math and map-making.

There is a story that after a discussion (about age 12) with his father related to career choices, the senior Gould dropped the boy off at a boarding school with 50 cents and a sack of clothes and wished him well.

After a few years of school, Gould dropped out to take work as a bookkeeper for a blacksmith. He eventually bought a half interest in the shop, then sold his half to his father and invested the proceeds in a New York City leather tanning business with one Charles Leupp.

Gould promptly set about trying to corner the leather hide market, involving his partner in the scheme. In the Panic of 1857, Leupp lost his entire fortune and took his own life. Later, Leupp’s family sued Gould for half the business; by this time Gould was wealthy but refused to satisfy the family. A lengthy legal battle ensued. Eventually, a court ruled against Gould and he was forced to sell.

From blacksmithing to tanning to the stock market

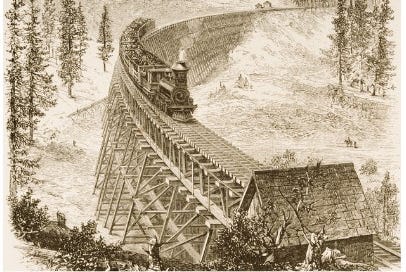

In about 1860 Gould began speculating in stocks. In the aftermath of the Panic of 1857, he was able to purchase a small upstate New York railroad for cents on the dollar. Working carefully to repair the railroad’s fortunes, he was able to sell it for a huge profit as the economy recovered.

With the proceeds, he went up against Cornelius Vanderbilt in the Erie Railroad War. In 1867, with partners Diamond Jim Fisk and Daniel Drew, Gould participated in a plan to issue fraudulent shares of Erie Railroad stock.

The plan worked, they bilked the uber-wealthy Vanderbilt out of $6 million, and a judge ordered them to appear in court. The trio fled to New Jersey, barricaded themselves in a hotel room and hired body guards for protection.

Tammany Hall

Desperately in need of defense against the powerful and purposeful Cornelius Vanderbilt, Gould and friends turned to the last, best refuge of the scoundrel: Politicians who could be bought.

The corrupt Democrat Party machine in New York City, known as Tammany Hall, was run by William “Boss” Tweed.

Gould reached out to Tweed, and generous bribes were transacted when Gould showed up in Albany with a bag containing half a million dollars in cash. The machinery of government thus lubricated, New York state legislation was adopted which retroactively made the bogus stock certificates legal.

A later Senate investigative committee discovered that one legislator had accepted a $75,000 payoff from Vanderbilt, and a second payoff of $100,000 from Gould. The legislator kept both.

As has been reported elsewhere, with the payoffs and shady legislation in place, the Erie Railroad War came to a close. Later, Vanderbilt recovered his losses from Gould’s partner Daniel Drew.

As a footnote, Boss Tweed was granted a lucrative seat on the board of the Erie Railroad in exchange for his help.

Conned by a Conman

With the end of the Erie Railroad War, Gould went in search of other schemes. He retained a controlling interest in the Erie Railroad, and was intent on adding another rail line to his portfolio. In making this intention known, he happened to catch the notice of a conman perhaps more clever than himself.

His real name having been lost to history, a Scotsman posing as a nobleman and offering the name Lord Gordon-Gordon had sailed for America and inserted himself lavishly into Minnesota society. He expressed an interest in purchasing the Northern Pacific Railroad headquartered there, on behalf of his fictitious Scottish interests.

Arriving in New York City in his tour of America, Gordon learned of the recent power struggle for ownership of the Erie Railroad and of Gould’s desire for an expanded rail empire.

Lord Gordon-Gordon had his mark selected.

Gordon let it be known in New York that his nonexistent Scottish investors were serious about acquiring the Northern Pacific, and had the financial resources to make it happen.

It was, of course, all made up.

The bait worked. Soon, Gould reached out to Gordon-Gordon. The Scotsman showed Gould letters of introduction from his Minnesota contacts and the two began discussions about pooling their resources to take control of the Minnesota line.

Interesting that both men were angling for control of the Northern Pacific, and each scheming to do so with the other’s money.

Gordon persuaded Gould to put up $1 million worth of Erie stock as a guarantee of his intention to partner in the Northern Pacific takeover. Gordon-Gordon assured Gould the stock certificates would not be sold; they were merely to be treated as earnest money.

Soon, however, Gould discovered the stock certificates were in fact being sold by Gordon. The conman had effectively stolen a million dollars from Gould. This was no doubt a serious affront to the dignity of the railroad magnate who considered himself the chief swindler in the country.

Gould brought legal action against Gordon, who fled to Canada. The news was big, and a group of prominent Minnesota businessmen, indignant at having been taken advantage of, funded a posse. They invaded Canada, kidnapped Gordon and sought to extradite him to the U.S. at gunpoint.

Authorities stopped them at the border, where the Americans were arrested and held in Canada without bail.

Minnesota Governor Horace Austin took steps to raise his militia and invade Canada to get the men back, making this an international incident. U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant had to get involved; his administration negotiated a legal extradition of Gordon-Gordon, who managed to commit suicide before he could be returned to stand trial.

Gould apparently never did anything small.

The fallout of this episode was lack of confidence in Erie Railroad stock. The value plummeted and the Board of Directors forced Gould out. He left, but his personal fortune — amassed primarily by taking advantage of others — had grown to some $25 million.

He looked for his next opportunity.

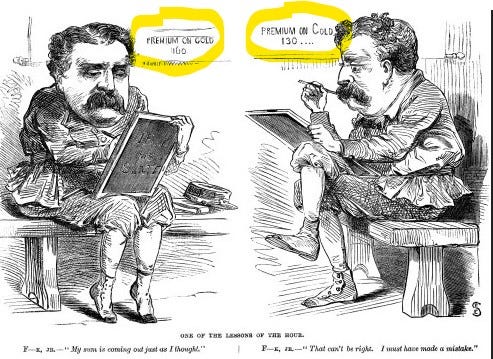

Black Friday, 1869

Continuing his relationship with his like-minded partner, Jay Gould proposed to Jim Fisk a plan to corner the U.S. gold market.

The idea was to quietly purchase gold bullion and let the price rise. What kept the price down was that the federal government, in a reasonable policy to stabilize the market after the Civil War, regularly offered gold bullion for purchase at a small discount.

I will not bore you with the complications of international finance (because the subject is beyond me anyway), but what Gould recognized was that the Union-dominated legislature had, during the Civil War, partially decoupled gold from paper currency. Domestic obligations of the United States were paid in paper; international accounts were settled in gold.

By playing off gold against greenbacks through commodity sales on the London market, a quick and clever manipulator could redeem English gold for U.S. currency and make a paper profit on the spread, then use the currency to purchase more gold at lower prices in the U.S. market.

Such manipulation drove the domestic price of gold steadily higher, but it only worked as long as the federal government chose to hold — and not sell — any of its gold. The amount of gold held by the feds dwarfed the private market.

Gould and Fisk needed the Treasury Department to cease the practice of selling gold, in order to let the price rise. In early 1869, the two approached the colorfully named Abel Rathbone Corbin, a brother-in-law to Ulysses Grant, who arranged an introduction to the brand new President.

Through the contact with Corbin, and also a friendly relationship with Daniel Butterfield, assistant U.S. treasurer, Grant was persuaded to cease the sales of gold.

As Gould and Fisk accumulated more and more of the commodity, and as the price rose, the plan was for the pair to liquidate their holdings just before the bubble burst.

They were almost too late. On one historic day, Grant was advised the price of gold had risen from a normal $135 per ounce to $161. He realized the plot, knew that he and the government had been swindled, and immediately ordered the Treasury to sell $4,000,000 in gold bullion.

Gould and Fisk worked in their investment war room continuing to purchase gold as the price climbed, until Gould that morning received a private word from Daniel Butterfield that Grant had ordered the Treasury sale.

Without alerting his long-time partner, Gould quietly issued sell orders for his own gold holdings. He liquidated most of his position while Fisk continued to buy.

Effectively, Gould was selling his overpriced gold to Fisk, who, unaware of the impending doom, greedily bought it up. As soon as the Treasury offer hit the street, the price instantly plunged from $160 to $133. Fisk suddenly lost millions. Investors lost confidence in the stock market, and thousands of accounts were wiped out on Black Friday, September 24, 1869.

Abel Corbin lost his investment. Butterfield lost his job.

Gould pocketed a tidy profit.

The public immediately became aware of the Gould/Fisk plot to corner the market. The two were chased first by chanting crowds and then by legal processes, but their cases were heard in New York where Tammany Hall had already been greased. Once again, Boss Tweed protected them.

The Final Years

Jay Gould had a way of being an unhealthy companion.

Like the tanner Charles Leupp many years earlier, Daniel Drew of the Erie Railroad War also was drained of money and, like Leupp, ended his life in suicide.

Boss Tweed was eventually tried and convicted on multiple charges of corruption and died in jail.

Three years after the Black Friday affair, Diamond Jim Fisk’s then-lover, a prostitute named Josie Mansfield, took up with another man. It became a tawdry and deadly lover’s triangle.

Josie and her new paramour Ned Stokes attempted to blackmail Fisk for $200,000. Instead of paying up, Fisk sued Stokes. Astonished and infuriated at Fisk’s resistance, Stokes murdered the financier in broad daylight in the lobby of New York’s Grand Central Hotel.

Upon conviction, Stokes spent 4 years in the Sing Sing Penitentiary.

If you are interested, the gun was a Colt House Revolver, which forever became popularly known as the Jim Fisk Pistol. It was a .41 rimfire 5-shooter, 2-5/8” barrel, using rear-loading metallic cartridges. (Nickel plated, spur trigger, birds-head grip.) It was produced by Colt’s from 1871 to 1876.

Jay Gould contracted tuberculosis and died in 1892 with an estate estimated between $70 and $100 million. The variance is attributed to Gould’s own obfuscation, as he attempted to shield assets from taxes.

In a fitting and unsurprising postscript, a Mrs. John Angell of Rouse’s Point, New York, claimed to have married young Jay Gould when he was only 17 years old, and further claimed they never divorced. Hence, she and her daughter laid claim to the Gould fortune.

Regrettably, I could not ascertain whether Mrs. Angell or her alleged daughter might have received any award.

Being in Jay Gould’s orbit, it would seem, was bad for one’s finances as well as for one’s health. Not to mention one’s moral compass.

Theological Contemplations

Where to begin?

Is there anything at all positive to be said of Jay Gould?

I actually cannot think of a single redeeming value.

1 Timothy 5:24 The sins of some are obvious, reaching the place of judgment ahead of them; the sins of others trail behind them.

In every review I have read of Gould, he swindled everyone he touched. From the perspective of 150 years distance, it is now virtually impossible to find anything positive.

1 Corinthians 15:33 Do not be deceived: “Evil company corrupts good habits.” Awake to righteousness, and do not sin; for some do not have the knowledge of God. I speak this to your shame.

In the case of the financially brilliant and morally bankrupt Jay Gould, everyone who was a close associate ended up broke, or dead, or in jail, or all three.

Proverbs 13:20 Walk with the wise and become wise, for a companion of fools suffers harm.

Harm, his companions suffered, indeed. Which means, that in spite of his riches, Mr. Gould was a fool.

I came across the following snippet of a conversation between Jay Gould and the pastor of his church. It is probably apocryphal, but it seems to fit the impression history has given us.

The minister of Jay Gould’s church asked the railroad tycoon where he might invest his life savings of $30,000.

Gould recommended the stock of the Missouri Pacific Railroad, and, sworn to secrecy, the minister followed his advice.

When the stock’s price lost most of its value, Gould reimbursed the minister for his losses, whereupon the contrite clergyman confessed to Gould that he had passed the tip along to several other members of the congregation.

Then Gould said, “Oh, I assumed you would. They were the ones I was after.”

And that is the story of Jay Gould. He is classed with the American Titans because of his railroad interests and because of his fabulous wealth, and because without him the Gilded Age would be considerably more drab. A producer of American greatness he was not.

Share the episode! Maybe this will be the warning, like the prophet Amos foretold, that snatches a burning brand from the fires of destruction!

Curt

Share this post