Arrested on a charge of cowardice in the face of the enemy! How could this be?

First, before we destroy the man’s reputation, let’s establish it.

Paul Revere (1734-1818), a Patriot leader of the American Revolution, was a prominent businessman in Boston and well known. Some probably considered him a citified dandy, but no one can argue with his leadership role in the Boston Tea Party (1773), for which he ran a very real risk of arrest and execution.

Nor can his role in establishing a rudimentary alarm system in the Massachusetts countryside be dismissed.

The Massachusetts colony had long been bedeviled by rocky relationships with native Americans, dating back to King Phillip’s War in 1675. After that conflict, English settlers concluded a system of communication was needed to alert one another of Indian uprisings.

A collection of bells, drums, gunfire, express riders and trumpets was used to sound alarms throughout the rural area north and west of the settlement at Boston. This was used, sometimes effectively, sometimes not, until the French & Indian War in 1754. That conflict brought an end to general hostilities, and the ancient alarm system fell into disuse.

As relations between the colonies and the Crown began to deteriorate, especially after the Stamp Act of 1765, Revere and others recognized that armed conflict would soon follow.

The Powder Alarm of 1774

Revere took the lead in reviving the rural alarm system. To do so, he visited most of the outlying settlements, urging their participation. He soon became known throughout the colony, gaining notoriety and respect.

Which he probably enjoyed. A lot.

The agreed rule was that the alarms would be activated if British troops in numbers greater than 500 left the environs of Boston.

The year after the Tea Party affair, the system was put to the test when Redcoats moved against a Patriot supply depot at Somerville, a few miles northwest of Boston. Royal troops seized assets in what became known as the Powder Alarm of 1774.

Local residents were outraged, but the alarm system failed the test. It was too slow and lacked participation.

These failures, along with the growing threat of physical confrontation with the British, spurred colonists to take it more seriously. Revere, again, was at the center of improvements and once again used his position with Patriot leaders to persuade support. People knew Revere and trusted him.

Hostilities commence

And then, the fateful night.

As early as April 7, 1775, Patriot leaders in Boston became aware that British troops were readying for action. Joseph Warren, President of the revolutionary Massachusetts Provincial Congress, ordered Revere to carry word to Patriots at Concord. Military supplies — guns, powder and shot — had been cached at Concord in preparation for militia action against the British. More importantly, Warren believed Samuel Adams and John Hancock were in residence there.

Adams and Hancock were recognized leaders of the brewing rebellion, and their capture by the British would be disastrous for the American cause.

On April 14, British General Thomas Gage in Boston received a dispatch from British Secretary of State William Legge to advance on Concord and seize or destroy war materiel. Whether he was to arrest Adams and Hancock was left unstated. Such an action would further infuriate the population, but Warren knew those two were in jeopardy. Revere was sent to find them.

Gage assigned Lt. Col. Francis Smith to proceed, “with utmost expedition and secrecy to Concord, where you will seize and destroy... all Military stores.... But you will take care that the soldiers do not plunder the inhabitants or hurt private property.”

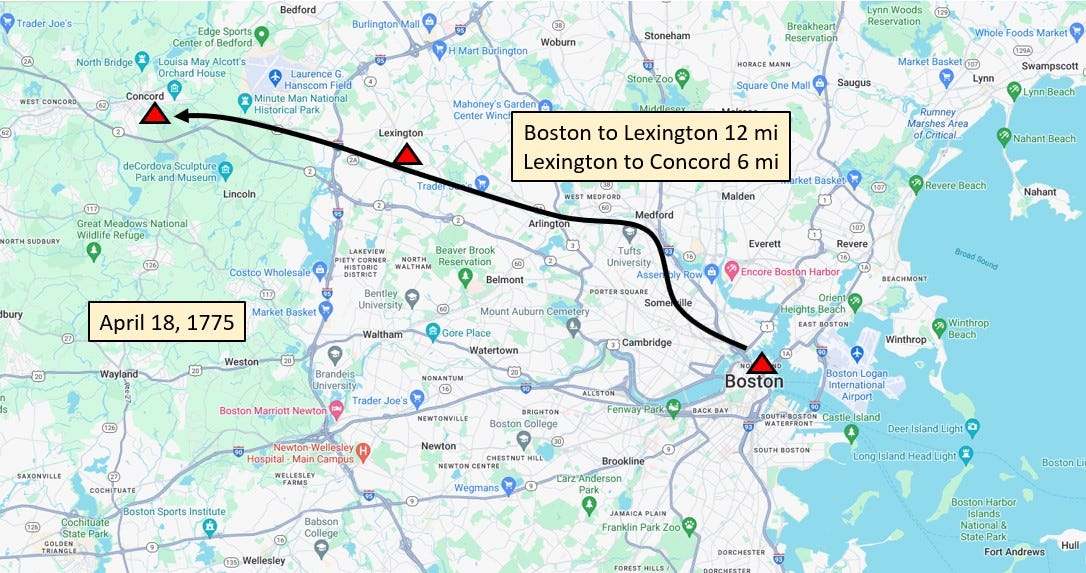

Smith led 700 Redcoats out of Boston on the evening of April 18, 1775. Of the 700, only 400 were able to return.

One if by land, two if by sea

While Patriot intelligence had confirmed the troops would march, they did not know the exact path they would take. It would make a difference. The British choices were to embark the troops on transports to cross the Charles River to Cambridge, the other to take the long way around and march the road along Boston Neck.

Revere himself crossed the Charles in a rowboat with oars muffled, pulling silently in the night past the HMS Somerset, a British man-of-war guarding the harbor. When he saw the previously arranged signal of two lanterns (“one if by land, two if by sea”) hanging in the belfrey of Old North Church, he knew the Redcoats would follow. He borrowed a horse and set out for Concord.

Unlike the rendition by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Revere did not simply gallop at full speed through sleepy towns shouting, “The British are coming!” for that would have been noted as the ravings of a mad man. All the colonists considered themselves British at the time, so it would have been nonsensical.

More likely, Revere would have announced, “The Regulars are coming out!” which does not have quite the same poetic cadence. In any case, Revere stopped at settlements along the way, dismounted and explained what he knew.

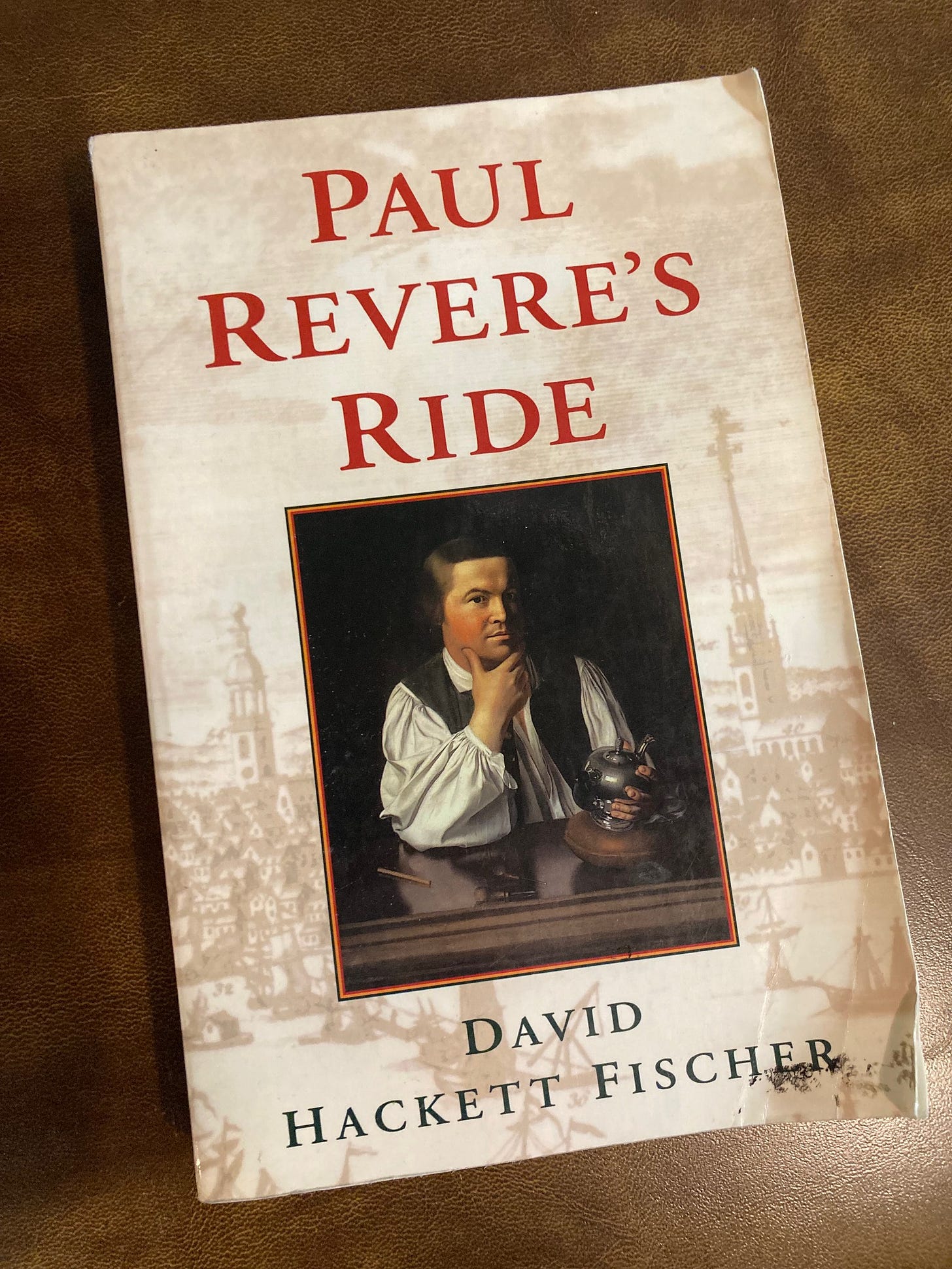

In David Hackett Fischer’s outstanding 1994 history, Paul Revere’s Ride, the case is made that without the personal relationships Revere had established with the people of rural Massachusetts, the warning would have lacked credibility. Paul Revere had invested years cultivating his acquaintances.

The people knew Revere, and his intelligence was accepted.

The rural alarms started before the Redcoats had even finished crossing the Charles River, and they still had a 12-mile march before them.

Express riders with a message

At Lexington in the middle of the night, and accompanied by William Dawes, Revere spent perhaps two hours with local militia leaders. There, they discovered Adams and Hancock; the two were not in Concord as expected. Nevertheless, knowing the British were after the military supplies at Concord, Revere and Dawes pushed on ahead of the Redcoats.

There were joined by Dr. Samuel Prescott, a resident of Concord, who had been in Lexington late at night visiting a local lady. Hearing the news, he was anxious to return home and warn his people.

The three made it a few miles to Lincoln where a British patrol intercepted them. Dawes and Prescott were able to escape on horseback.

Dawes fell from his horse a few yards away and was set afoot. Prescott, impressively, jumped a barricade and made good his escape, winding his way through the woods to Concord and sounding the alarm.

What is described as Prescott’s “superb horsemanship” may or may not have been fueled by the prospect of having to explain publicly what he had been doing in the residence of a proper lady, 6 miles from his home, after midnight.

Revere was captured, and there his midnight ride ended. Being set free later in the morning hours, he made his way back to Lexington in time to witness the dawn confrontation.

The shot heard ‘round the world

Col. Smith’s 700 troops faced off against fewer than 100 militia, farmers and merchants, at a range of 75 yards. Despite orders on both sides to hold their fire, shots suddenly rang out. Reports vary, but likely there were several shots at once and were probably started either by startled troops (both sides were very green) or by a single hothead (which could have been from either side) who decided it was time to go to guns.

Most of the militia broke and ran, but a few stood and exchanged fire. These ended up dead. The Patriots lost 8 killed and others wounded. The British lost one.

The shot heard round the world launched 8 years of war.

Later in the morning, the Regulars arrived at Concord, discovered most of the supplies they sought had already been removed to safety, and faced a long, grueling 16-mile march back to Boston under harassing fire on the road.

The war had begun unspectacularly for the British. Patriot spirits were aroused, and were further enflamed two months later when the British were driven from Boston at Bunker Hill. That was where Joseph Warren, commissioned as a General but fighting as a Private, met his heroic end.

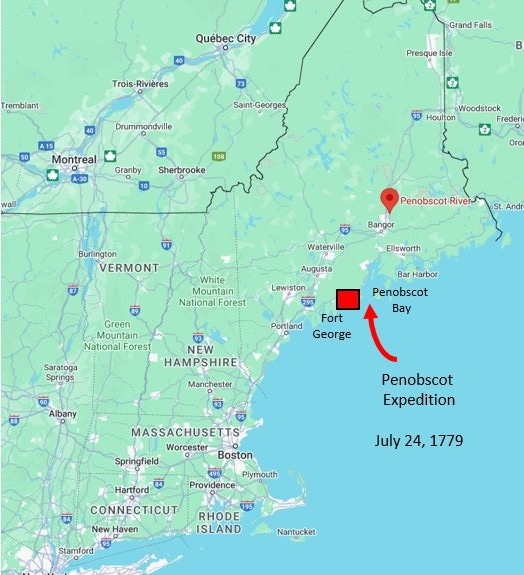

The war stumbled forward. By 1779, British General Sir Henry Clinton decided to move against the southern colonies, hoping to find welcome among loyalist families there. In doing so, the British recognized they needed a stronger base of operations further north.

They chose to fortify the harbor at Penobscot Bay, further up the coastline. British Brigadier General Francis McLean took a force of 700 troops north. His naval commander was Captain Henry Mowat, who had command of 6 warships and 6 troop transports. On July 18, 1779, they commenced construction of Fort George, near Castine, Maine.

The disaster of the Penobscot Expedition

The Massachusetts General Court, the legislative body, ordered a response. Brigadier General Solomon Lovell was assigned to lead 900 troops. American Navy Captain Dudley Saltonstall commanded 18 warships (navy and privateer) and 22 troop transports. It was the largest fleet deployed by that point in the revolution.

Lt. Col. Paul Revere was among Lovell’s officers.

It is important to note that besides the 900 minutemen who responded, another 500 failed to show up for duty. Also, there was exactly zero experience in amphibious landings, whether opposed or not. None of the ships had ever operated as part of a fleet before. To the privateers, fleet operations were completely unknown. To say it was a motley assortment would be a compliment.

For the Patriots, the Penobscot Expedition was a complete disaster.

Capt. Saltonstall refused to take his gunships into the harbor because of the British ships anchored there. General Lovell held one council of war after another, none with any conclusive plans hatched.

Personalities interfered. Fellow officers reported Col. Revere to be arrogant, uninvolved and not open to suggestion. In the historical fiction The Fort, Bernard Cornwell (author of the hugely popular Sharpe’s Rifles series) suggests that on one occasion, Revere refused to show up on shore for a dawn attack, preferring to finish his breakfast aboard his transport ship. This may be an apocryphal account, but is consistent with other reports.

On another occasion, Revere refused to assist in evacuating Patriot sailors from their disabled ship because his light boat was filled with his own baggage and therefore could not be used.

One critical oversight by the Massachusetts General Court was that no overall commander for the expedition had been established. Cooperation was merely expected. Or perhaps hoped-for. It did not materialize.

Burn the boats, burn the careers

In the end, a British relief fleet arrived by sea with 6 warships. Alarmed, most of the American fleet escaped battle by going inland, up the Penobscot River, and to avoid capture, burned their ships. Every American vessel in the expedition was lost, including Warren, the 32-gun flagship.

American soldiers and sailors found their way home, eventually, through the northeast forest.

Captain Saltonstall was court-martialed and dismissed from the the Navy. Revere was relieved of command and placed under house arrest. Charged with misconduct, “disobedience of orders and unsoldierlike behavior tending to cowardice,” he demanded a court martial to clear his name.

Two years after the humiliating Penobscot defeat, the court cleared Revere of misdoing by announcing he had performed “with equal honor as the other officers in the expedition.” This was hardly a rousing affirmation of his performance, but Revere publicly claimed it had completely exonerated him.

Revere’s reputation was permanently tarnished, even as he re-engaged in commercial business in Boston.

Paul Revere died in 1818, a moderately successful businessman. His gravesite in the Granary Burying Ground in Boston is marked by an impressive headstone, honoring him for his role in the Revolution.

Revere’s reputation was suddenly given new life 45 years after his death with The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere.

For all the man’s shortcomings, and the poem’s inaccuracies, I prefer to remember Longfellow’s version of that marred and indispensable Patriot.

Takeaways

Most significant moral failures occur in the fourth quarter.

This was the subject of my blog Maturity, Wisdom, and Shopping Cart Wars posted 2/7/24. A brief survey of Jewish kings in the Old Testament who began well and ended badly, did so because they made wrong moral choices in the last years of their lives.

Paul Revere may have been the arrogant and prickly individual depicted in the Penobscot Expedition. These characteristics would not have been inconsistent with his initiative in developing an effective rural alarm system in Massachusetts in 1774.

If so, he got a 40-year jump on heading for moral decline.

Uncertain leadership by one results in costly defeat for all.

Notwithstanding the failure of the Massachusetts General Court to clearly define command responsibility for the Penobscot affair, no one in the expedition stepped forward in the extremity to show a path forward. Perhaps their assignment was an impossible task, but even so, it ended in complete humiliation.

1 Corinthians 14:8 “If the trumpet does not sound a clear call, who will get ready for battle?”

In family, in church, in business and in government, confident leadership is essential to effective action.

“Past Performance Is Not Indicative Of Future Results”

It’s not just the Securities and Exchange Commission that offers this warning. Solomon said, “The end of a matter is better than its beginning…” Ecclesiastes 7:8.

Revere’s likely prickly personality aside, he did a very good thing in sounding the alarm in the Massachusetts countryside. It is quite important to note his performance was not a standalone event. He had prepared relationships with the populace ahead of time, so that on the evening of April 18, 1775, he was welcomed into the homes of people who knew him.

This victory did not abandon him, and indeed led to lasting fame via Longfellow’s poem, but it neither assured nor excused his behavior at Penobscot Bay.

Each day we have the opportunity to choose a path. Perhaps that is why Joshua said, “Choose for yourselves this day whom you will serve…” Joshua 24:14, emphasis added.

Settling on a life direction is a decision that each of us will make, either intentionally, by verbalizing to ourselves the principles that will guide us, or unintentionally, by allowing circumstances to blow us where they will.

Robert Urich’s character (Jake Spoon) in Lonesome Dove is hanged for stealing horses. The dialog is haunting. When Robert Duvall as Gus McRae tells him, “You know how it works, Jake. You ride with an outlaw, you die with an outlaw. I’m sorry you crossed the line,” Jake replies in desperation: “I didn’t see no line, Gus!”

May we each be courageous and attentive to set a right course, and follow it all our days.

And now, because it is in the public domain, I give you:

The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1863

LISTEN, my children, and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-five;

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year.He said to his friend, “If the British march

By land or sea from the town to-night,

Hang a lantern aloft in the belfry arch

Of the North Church tower as a signal light, —

One, if by land, and two, if by sea;

And I on the opposite shore will be,

Ready to ride and spread the alarm

Through every Middlesex village and farm,

For the country folk to be up and to arm.”Then he said, “Good night!” and with muffled oar

Silently rowed to the Charlestown shore,

Just as the moon rose over the bay,

Where swinging wide at her moorings lay

The Somerset, British man-of-war;

A phantom ship, with each mast and spar

Across the moon like a prison bar,

And a huge black hulk, that was magnified

By its own reflection in the tide.Meanwhile, his friend, through alley and street,

Wanders and watches with eager ears,

Till in the silence around him he hears

The muster of men at the barrack door,

The sound of arms, and the tramp of feet,

And the measured tread of the grenadiers,

Marching down to their boats on the shore.Then he climbed the tower of the Old North Church,

By the wooden stairs, with stealthy tread,

To the belfry-chamber overhead,

And startled the pigeons from their perch

On the sombre rafters, that round him made

Masses and moving shapes of shade, —

By the trembling ladder, steep and tall,

To the highest window in the wall,

Where he paused to listen and look down

A moment on the roofs of the town,

And the moonlight flowing over all.Beneath, in the churchyard, lay the dead,

In their night-encampment on the hill,

Wrapped in silence so deep and still

That he could hear, like a sentinel’s tread,

The watchful night-wind, as it went

Creeping along from tent to tent,

And seeming to whisper, “All is well!”

A moment only he feels the spell

Of the place and the hour, and the secret dread

Of the lonely belfry and the dead;

For suddenly all his thoughts are bent

On a shadowy something far away,

Where the river widens to meet the bay, —

A line of black that bends and floats

On the rising tide, like a bridge of boats.Meanwhile, impatient to mount and ride,

Booted and spurred, with a heavy stride

On the opposite shore walked Paul Revere.

Now he patted his horse’s side,

Now gazed at the landscape far and near,

Then, impetuous, stamped the earth,

And turned and tightened his saddle-girth;

But mostly he watched with eager search

The belfry-tower of the Old North Church,

As it rose above the graves on the hill,

Lonely and spectral and sombre and still.

And lo! as he looks, on the belfry’s height

A glimmer, and then a gleam of light!

He springs to the saddle, the bridle he turns,

But lingers and gazes, till full on his sight

A second lamp in the belfry burns!A hurry of hoofs in a village street,

A shape in the moonlight, a bulk in the dark,

And beneath, from the pebbles, in passing, a spark

Struck out by a steed flying fearless and fleet:

That was all! And yet, through the gloom and the light,

The fate of a nation was riding that night;

And the spark struck out by that steed, in his flight,

Kindled the land into flame with its heat.He has left the village and mounted the steep,

And beneath him, tranquil and broad and deep,

Is the Mystic, meeting the ocean tides;

And under the alders that skirt its edge,

Now soft on the sand, now loud on the ledge,

Is heard the tramp of his steed as he rides.It was twelve by the village clock,

When he crossed the bridge into Medford town.

He heard the crowing of the cock,

And the barking of the farmer’s dog,

And felt the damp of the river fog,

That rises after the sun goes down.It was one by the village clock,

When he galloped into Lexington.

He saw the gilded weathercock

Swim in the moonlight as he passed,

And the meeting-house windows, blank and bare,

Gaze at him with a spectral glare,

As if they already stood aghast

At the bloody work they would look upon.It was two by the village clock,

When he came to the bridge in Concord town.

He heard the bleating of the flock,

And the twitter of birds among the trees,

And felt the breath of the morning breeze

Blowing over the meadows brown.

And one was safe and asleep in his bed

Who at the bridge would be first to fall,

Who that day would be lying dead,

Pierced by a British musket-ball.You know the rest. In the books you have read,

How the British Regulars fired and fled, —

How the farmers gave them ball for ball,

From behind each fence and farm-yard wall,

Chasing the red-coats down the lane,

Then crossing the fields to emerge again

Under the trees at the turn of the road,

And only pausing to fire and load.So through the night rode Paul Revere;

And so through the night went his cry of alarm

To every Middlesex village and farm, —

A cry of defiance and not of fear,

A voice in the darkness, a knock at the door,

And a word that shall echo forevermore!

For, borne on the night-wind of the Past,

Through all our history, to the last,

In the hour of darkness and peril and need,

The people will waken and listen to hear

The hurrying hoof-beats of that steed,

And the midnight message of Paul Revere.

From The Complete Poetical Works of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1903

Thanks for joining us. For more in our American Warriors series, please subscribe to The Alligator Blog.

Share this post